Wood Belt Sanding: Grit Sequence for Sanding Belts

You notice it the moment the light angles in—those faint stripes that refuse to disappear, telegraphing through the first coat of finish like ghosted fingerprints. They’re the memory of rushed prep, of skipped grits and overheated passes. Anyone who has carried a tabletop into the sun and watched it betray a thousand micro-scratches knows the sting. Precision starts long before the finish can, and the most reliable way to get there is a disciplined grit sequence paired with the right sanding belts. Whether you run a 37-inch wide-belt sander in a small shop or rely on a handheld belt sander to flatten stubborn stock, the same physics apply: remove the deepest scratches with efficiency, generate finer, uniform scratches, and stop at the highest grit that supports your finish system without burnishing the surface.

Belt sanding is deceptively simple—stock goes in rough and comes out flat. But if the scratch pattern isn’t controlled, you’ll pay for it later with orbital sanding that never seems to end, blotchy stain, or edge lines that pop under raking light. The right sequence should feel almost mechanical: predictable, repeatable, and tuned to your substrate, machine, and belt chemistry. You’re not just smoothing wood; you’re creating a controlled surface texture that finishes can wet into, bond with, and highlight. With a calibrated approach to grit jumps, feed speeds, belt choices, and heat management, you move from guesswork to a stable, professional process that holds up in daylight.

Quick Summary: Choose a starting grit based on surface roughness, step through controlled grit jumps (often 80→120→180), match belt chemistry to species, manage heat and dust, and verify scratch removal with raking light and witness marks.

From mill marks to flat: scope and constraints

A belt sander’s first obligation is geometry: achieve flatness while erasing planer and jointer marks. On a wide-belt sander, that job typically falls to the contact drum for material removal and the platen (when engaged) for scratch refinement. On handheld belt sanders, the platen is fixed, so pressure control and pad compliance are your tools. Before selecting a grit sequence, establish your constraints:

- Incoming surface profile: Planer scallops and tear-out require coarser entry (P60–P80). If stock is already machine-flat with faint lines, you can begin at P100–P120.

- Veneer thickness: Thin face veneers force a conservative approach—minimal passes and limited grit range (often stopping at P150–P180) to avoid over-thinning and burnishing.

- Finish system: Oil and solvent-borne film finishes tolerate P180–P220 pre-sand. Waterborne topcoats benefit from slightly finer or pre-raised surfaces, but don’t exceed the manufacturer’s upper limit or you’ll reduce adhesion.

- Throughput and horsepower: Low-HP wide-belt machines prefer smaller depth of cut and more passes. Aggressive grit jumps can stall the machine and glaze belts.

A disciplined belt process solves three problems simultaneously: it levels, it standardizes scratch geometry, and it delivers a surface that downstream sanding can refine quickly. The “secret” is proportionality—each grit must remove the previous scratch depth completely, with minimal over-sanding. A common failure mode is starting too fine: P120 trying to erase planer marks takes too many passes, generates heat, and polishes early fibers, setting up uneven stain absorption. Start coarse enough to gain control, then make rational jumps.

A practical setup sequence might look like this for solid hardwood panels: drum only at P80 for flatness and defect removal; drum plus platen at P120 for scratch refinement; platen-light at P180 for finish-ready texture. Each pass must be validated under raking light; if you still see P80 lines after P120, you didn’t actually graduate the surface—you just created a blended mess that will reappear under finish.

Calibrating grit jumps for sanding belts

The core rule for grit progression is geometric: each grit should be about 1.4–1.6× finer than the previous step. This ratio ensures the new abrasive can fully remove the prior scratch valley without needless stock loss. In practice, that maps to common woodworking steps like P80→P120→P180 (1.5× and 1.5×), or P60→P100→P150 when heavier stock removal is required. Going P80→P150 looks tempting, but often leaves P80 scratches hiding until finish.

Typical wide-belt sequences

- Heavy calibration or cupped glue-ups: P60→P100→P150, optionally P180 on the platen for film finishes.

- Standard solid wood prep: P80→P120→P180. This is the shop workhorse because it balances removal rate with scratch refinement.

- Veneered panels: P120→P150→P180. Avoid over-sanding; let edge trimming and finer orbital passes do the last 10%.

Handheld belt sander sequences

- Rough flattening: P60→P100, then transition to a random-orbit sander at P120 or P150 to erase belt directionality.

- Edge and end grain: P80→P120→P150; dwell time must be controlled to prevent dishing earlywood.

Why not micro-step (e.g., P80→P100→P120→P150→P180)? On a wide-belt sander with limited HP, that can indeed run cooler, but it often costs throughput with negligible gains if your belt chemistry and machine setup are dialed. Conversely, skipping too far (P80→P180) leaves subsurface valleys that telegraph during dye or under high-gloss.

Grit labels matter. Use FEPA “P” graded belts (e.g., P120) for consistent scratch behavior across brands. Aluminum oxide belts are the default for wood; zirconia and ceramic excel at heavy, cool cutting on dense species (maple, hickory) but can over-cut softwoods if pressure is not reduced. Closed-coat belts cut aggressively and leave a denser scratch field; open-coat belts resist loading on resinous pine. Jumps should be validated with witness pencil lines and raking light at each stage—if your P120 pass doesn’t erase all P80 scratches within two to three light passes, revisit belt condition, pressure, and feed.

Species, moisture, and belt chemistry

Not all wood abrades the same. Two planks exiting the planer with similar scallops can behave differently under the same belt sequence because density, resin content, and moisture distribution change the cut mechanics.

- Hard maple, hickory, exotics: Dense, brittle fibers favor sharp, cool-cutting abrasives. Zirconia or ceramic sanding belts at P80 and P120 keep temperatures down and reduce glazing. Finish at P150–P180 before moving to orbital sanding. Watch for burnishing—reduce platen pressure and consider open-coat aluminum oxide at the last pass if glazing appears.

- Red oak, ash: Ring-porous anatomy can trap fines; aggressive closed-coat P80 clears early, but switch to open-coat at P120 or P150 to limit loading, then conclude at P180.

- Pine, fir, cedar: Resin-rich and soft. Start finer (P100) if the stock is flat to avoid deep grooves that telegraph. Use open-coat aluminum oxide belts and lower pressure; heat will set pitch and load belts.

- Walnut, cherry: Prone to burnishing and heat darkening. Favor fresh belts, shorter dwell, and modest platen pressure. P80→P120→P180 is safe; avoid over-sanding with high platen contact at the final pass.

Moisture content also shifts behavior. Elevated MC makes fibers smear rather than abrade, creating shiny, compressed surfaces that reject stain. If your stock is above 10–12% MC, reduce platen use and dwell, and consider pausing final passes until equilibrium. Seasonal movement can also change flatness; when sanding panels built from recently milled boards, leave a light margin for final touch-up after acclimation.

Abrasive backing and joint style matter in wide-belt work. X-weight cloth backings provide the stability needed for aggressive passes. Lap joints are smoother running at high speeds; butt joints can introduce a periodic mark if tracking or tension is off. For portable belt sanders, X-weight or heavy paper backings with anti-static treatments reduce dust clinging and lateral scratches.

Finally, consider coat density and anti-static treatments. Closed-coat belts generate a uniform scratch pattern but load faster on resinous woods; open-coat alleviates loading at the cost of slightly less uniformity, which is acceptable at intermediate grits. Anti-static belts evacuate dust more effectively, lowering temperatures and improving scratch clarity—a small premium that pays off in consistent finishing.

According to a article.

Machine setup and tracking for clean passes

Grit sequence is only as good as the machine that executes it. A well-tuned wide-belt sander creates predictable scratch fields; a misaligned one prints defects with precision. Start with calibration:

- Belt tracking: The belt should oscillate gently across the platen/drum face; excessive oscillation leaves lateral marks, while insufficient motion grooves the belt. Verify oscillation sensors and air jets are clean and responsive.

- Tension and crown: Proper tension stabilizes tracking and keeps the belt cutting flat. Check manufacturer specs and confirm the contact drum’s crown is uniform; a low crown or uneven tension prints stripes.

- Pressure settings: Use segmented platen pressure conservatively. For the coarse pass, run drum-only to avoid pressing coarse grit into earlywood and creating dish. Introduce the platen at the intermediate grit to refine scratches. For the final grit, reduce pressure and dwell to prevent burnishing.

- Feed speed and cut depth: Slowing the feed increases contact time and heat; if you need more removal, increase cut depth via drum height rather than just slowing feed. Aim for shallow, consistent removal—think 0.1–0.3 mm per pass for mid-grits, less on veneer.

Handheld belt sanders thrive on stability and control. Fit a flat, rigid platen, keep the tool moving, and overlap passes by 50%. Avoid tipping at edges—use sacrificial runners or edge guides to hold the sole flat as you exit the panel. When transitioning to a random-orbit sander, align the ROS grit with the last belt grit or one step finer (e.g., belt P120 to ROS P150) to erase directionality efficiently.

Validation is non-negotiable. Use raking light and a soft pencil grid before each grit; sand until the grid is completely and uniformly removed, then stop. A magnifier helps identify surviving coarse scratches. When you see heat haze (slight gloss, darkened tracks) or smell resin, your pass is too long or pressure too high. Back off, clean or swap the belt, and reduce dwell. Remember: a belt is a cutting tool. Dull abrasives rub and burn; fresh abrasives cut cool and straight.

Dust, heat, and loading control

A belt’s cutting efficiency is linked to temperature and chip evacuation. Overheated scratches fracture unpredictably and compact fibers, while loaded belts skate and polish instead of cut. Your job is to keep the interface cool, clean, and open.

- Dust extraction: Target at least 350–450 CFM per port on small wide-belt machines, with smooth ducting and minimal static pressure loss. Anti-static hoses reduce fines clinging to equipment, improving airflow. Check and clean the extraction hood and curtains; caked dust starves the belt.

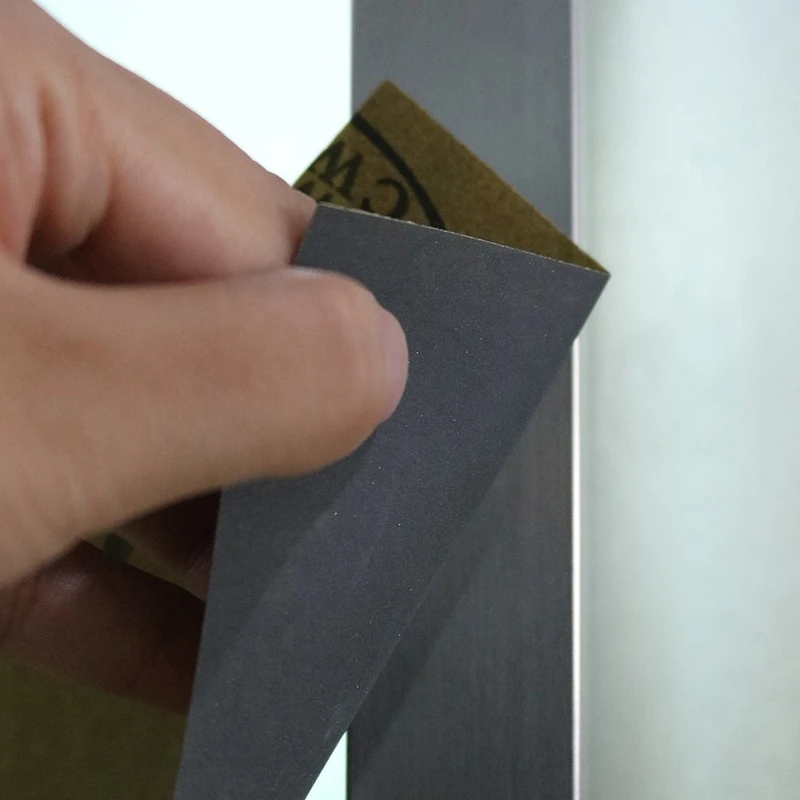

- Belt cleaning: For wide-belts, rely on in-machine cleaning via compressed air or dedicated cleaning blocks designed for production; do not jam crepe sticks into moving wide belts. For handheld belt sanders, crepe rubber cleaning blocks are effective—apply lightly while the belt spins at no-load.

- Heat management: Avoid excessive feed slowdown to “get it cleaner”—you’re increasing dwell and burn risk. Instead, sharpen the process: fresh belt, correct grit, proper cut depth. If a belt feels warm to the touch between passes, you’re on the edge of glazing.

- Loading prevention: On resinous species, switch to open-coat aluminum oxide for intermediate and final passes. Reduce platen pressure and consider a slightly faster feed to move chips. Anti-static belts and well-grounded machines reduce fines adherence that leads to secondary scratches.

- Witness and reset: If you detect pitch tracks, stop and clean or replace the belt immediately. Contaminated belts create consistent defects that require backing up one grit to erase.

Actionable tips:

- Run coarse passes drum-only; add the platen only at P120 and finer.

- Use open-coat belts at P120+ on pine and fir to resist pitch loading.

- Record a baseline: for each machine/species combo, log pass count, feed speed, pressure, and results; repeatability is throughput.

- Establish a belt retirement rule: if scratch clarity degrades or heat rises at normal settings, change belts—don’t chase with slower feeds.

A cool, clean process not only improves surface quality but extends belt life, making your sequence both efficient and economical.

Workflow examples and troubleshooting

Applying these principles, here are reference workflows you can adapt.

Solid maple tabletop, 1.25 in thick, light planer scallops

- P80 drum-only, 1–2 light passes until pencil grid is gone.

- P120 drum + light platen, one pass; verify under raking light for uniform scratch.

- P180 platen reduced pressure, one pass.

- Transition to ROS P180→P220 with a soft interface pad for edge blending. Stain/finish per system.

- Watchouts: maple burns—if you see haze at P120, swap to fresh zirconia belts.

Walnut cabinet doors with 0.6 mm veneer

- P120 drum-only, minimal removal to flatten.

- P150 platen light, one pass.

- P180 platen feather, one pass max.

- ROS P180 with minimal dwell. Avoid exceeding P180 on the belt sander to keep veneer safe.

- Watchouts: burnishing at stile/rail joints—reduce pressure mid-panel.

Pine shelving, resinous streaks

- P100 open-coat AO, drum-only.

- P150 open-coat, introduce platen gently.

- P180 open-coat with low pressure; clean belt between passes.

- ROS P180→P220; raise grain with a water mist if using waterborne finish, then a light P220 scuff.

- Watchouts: belt loading—clean early and often.

Troubleshooting patterns:

- Persistent coarse lines after two grits: Your jump is too large or belts are dull. Back up one grit, replace belts, verify pressure and feed.

- Washboarding or zebra stripes: Check belt splice, drum crown, and tracking oscillation. A worn or flat crown prints at a regular pitch.

- Glossy, compressed patches: Overheating. Reduce dwell, lower pressure, and ensure dust extraction is effective. Consider switching chemistry for hard species.

- Edge burn-through on veneer: Platen pressure too high or belt overhang at the panel edge. Use a spoil board or edge protector and lower pressure.

Decision checkpoints:

- If the intermediate grit ever requires more than two passes to remove the previous scratch fully, reconsider the starting grit.

- If your final pass shows directionality under raking light, lighten platen pressure or switch to a slightly finer belt for a single, quick refinement.

The Only 3 — Video Guide

This short video breaks sanding media down to the core essentials, arguing you only need a small, smart set of grits for most work. It walks through which papers to buy, when to reach for them, and how to avoid overspending on redundant options, using real-world examples and practical tips.

Video source: The Only 3 Sandpapers You Really Need | SANDING BASICS

240 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (25-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Smooth-cut abrasive for soft blending, de-nibbing, and light surface preparation before polishing or coating. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What’s the best grit sequence for solid wood on a wide-belt sander?

A: A reliable baseline is P80→P120→P180. Start at P60 only if you need significant flattening, and stop at P150 for softer woods or stain-sensitive species. Validate each step with raking light and pencil witness marks.

Q: Should I ever skip from P80 directly to P180?

A: Not on belt sanders. That jump often leaves P80 valleys that reappear under finish. Keep jumps around 1.4–1.6× (e.g., P80→P120→P180) so each pass fully removes the prior scratch.

Q: Which sanding belts are best for hard maple and other dense species?

A: Zirconia or ceramic belts at the coarse and intermediate grits run cooler and cut longer on dense hardwoods. Finish with aluminum oxide at P180 to avoid over-aggressive cutting that can burnish fibers.

Q: How do I prevent belt loading on resinous pine?

A: Use open-coat aluminum oxide belts, ensure strong dust extraction, keep feed speed reasonable, and clean belts frequently. Reduce platen pressure on the final pass to minimize heat.

Q: When should I switch from a belt sander to a random-orbit sander?

A: After the intermediate or final belt grit—commonly after P120 or P150 on handheld belt sanders, and after P180 on wide-belt sanders—so the ROS can efficiently remove belt directionality and prepare for finish.