Wet Dry Sandpaper Soak Times: A Technical Guide

The shop is quiet except for the slow drip from a rinse bottle, pooling across a workbench where a clear-coated guitar body breathes under the lights. There’s a shallow tray of clean water, a few folded sheets of wet dry sandpaper, and a foam pad waiting like a promise. You press a fingertip to the lacquer—weeks of curing have left it hard, crisp, and unforgiving. You remember the last time you rushed the process and chased pigtails under a glaring shop light. Not today. Today, the water will do its work before the first stroke lands.

In high-stakes surface preparation—be it leveling a new automotive clear, refining a sprayed varnish on walnut, or knocking back dust nibs on a polished resin cast—the details you can’t see often determine the outcome you can. Soaking is one of those details. It sounds trivial: drop the sheet in, wait a bit. But how long you soak, and what you soak in, measurably alters abrasive behavior—stiffness, loading rate, slurry formation, and scratch consistency. With wet dry sandpaper, the bond system and backing saturate, the sheet relaxes and conforms, water displaces air within the abrasive field, and the first cut becomes controlled rather than grabby.

The goal is not to waterlog the sheet. It’s to coax it into a state of predictable compliance: flexible enough to contour, resilient enough to cut cleanly, and lubricated just enough to carry debris away without floating the abrasive. Over-soak and you risk adhesive creep, edge shelling, and premature grit loss—especially on older or economy papers. Under-soak and the sheet acts like a dry abrasive in the first passes: sharp, but skittish, prone to micro-gouging and erratic scratch depth.

If perfection lives in the last percent of your workflow, soak time is one of the quiet levers you can pull to get there.

Quick Summary: Optimal soak time for wet/dry sheets is typically 5–15 minutes for modern waterproof papers and 1–3 minutes for film-backed abrasives—just enough to relax the backing and pre-wet the abrasive without weakening the bond.

Why Soak Abrasives at All

Wet sanding turns the cutting zone into a managed micro-slurry. The water acts as a lubricant and carrier, lowering friction, cooling the surface, and suspending swarf so the grains keep cutting rather than plowing loaded debris. Soaking is the preconditioning step that makes this fluidized cut more consistent from the first stroke.

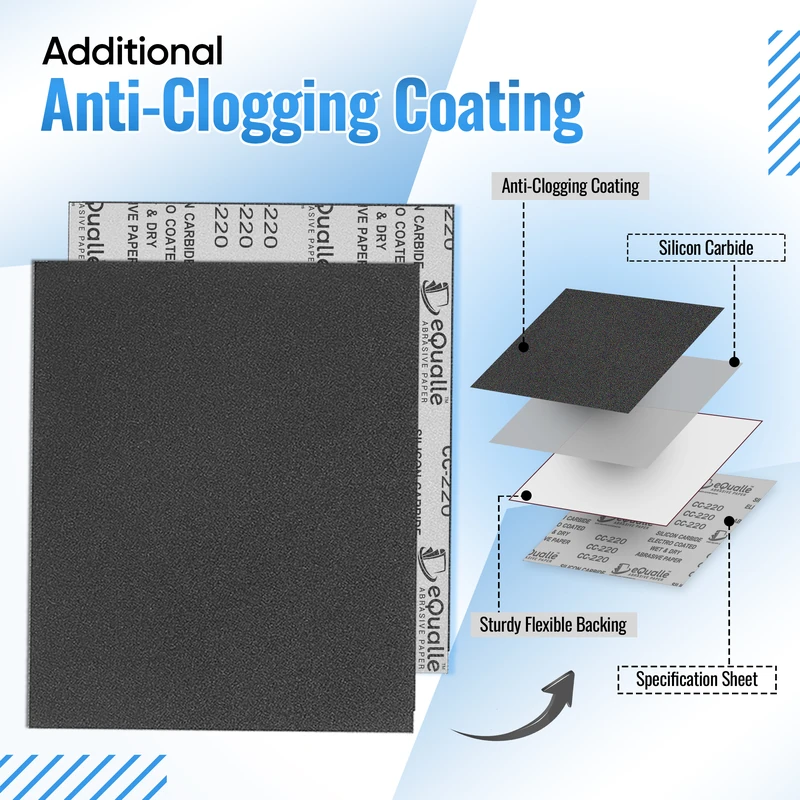

Most wet/dry sheets are silicon carbide grains held in a resin-over-resin bond on a waterproofed backing. On paper-backed sheets, latex saturation imparts flexibility and water resistance, but the fibers still need time to relax. A short soak reduces curl, softens the sheet’s hand, and allows the initial passes to conform rather than scratch at high points. Film-backed sheets (polyester) don’t absorb water, but their surfaces still benefit from pre-wetting: water displaces air between grain tips, and surfactants reduce surface tension so the sheet rides a consistent fluid layer.

Mechanically, soaking modifies the abrasive system in three ways:

- Reduces stiction on the first passes, lowering the risk of deep, isolated scratches from dry contact.

- Stabilizes the scratch pattern by promoting an even slurry, which acts as a secondary abrasive of finer equivalent grit.

- Increases fold resilience and edge flexibility, so sheets can wrap a block or pad without cracking the bond line.

The failure mode for over-soaking is subtle: resin bonds are water-resistant, not waterproof in perpetuity. Extended submersion can promote hydrolytic weakening at the edges, leading to grit shedding and premature dulling. With cloth-backed micro-abrasives, excessive soak times can loosen the weave and shift the grain alignment. The sweet spot is long enough to saturate the paper or pre-wet the film, short enough to protect the adhesive system.

Dialing In wet dry sandpaper soak time

Soak time is not one-size-fits-all. It depends on backing type, grit size, and the demands of your finish.

- Film-backed micro-abrasives (P1500–P5000+): 1–3 minutes. These sheets don’t absorb water; a quick dunk ensures an even water film and clears any manufacturing dust. Longer soaks add no benefit.

- Modern waterproof paper (A/C/D weight, silicon carbide, P320–P2000): 5–15 minutes. This window relaxes latex-treated fibers and gives the sheet a uniform, supple feel. Start at 5 minutes; extend to 10–15 if a sheet feels stiff or curls.

- Economy or older waterproof papers: 10–20 minutes, with caution. Test a strip first. If the edges soften excessively or shed grain when rubbed, reduce soak time.

- Sanding sponges and foam-backed pads: No soak, just pre-wet. Foam cells absorb plenty of water instantly; submersion can trap debris that releases unpredictably.

- Cloth-backed micro-mesh: 1–5 minutes pre-wet only. The fabric doesn’t need saturation; you’re hydrating the cutting surface.

Five actionable tips for exact soak control:

- Score the corner test: After soaking, fold a sheet corner over your nail. It should flex without cracking the resin. If it creases sharply or looks chalky, you under-soaked; if it feels mushy at the edge, you over-soaked.

- Stage grits in labeled trays: Keep P800, P1200, P2000 in separate shallow pans with fresh water. Cross-contamination between grits is a common cause of rogue scratches.

- Use a timer: Consistency beats guesswork. A simple 10-minute timer prevents “accidental overnights.”

- Pre-load the pad: Dip your interface pad or block briefly so it doesn’t wick water from the sheet and dry the cut.

- Rotate sheets, not water: Change water at each grit step; never carry slurry forward. Fresh fluid equals predictable scratch profiles.

Avoid the myth of overnight soaking. It originated to tame very stiff, early-generation papers. Modern resin systems and waterproof backings simply don’t need it—and prolonged exposure invites bond failure.

Water, Additives, and Temperature Control

The fluid you sand with matters. Tap water works, but minor adjustments improve both cut and clarity. A few drops of a mild, non-silicone dish detergent per liter (roughly 0.1–0.2%) lowers surface tension and helps the water sheet under the abrasive, preventing stick-slip events. For automotive finishing where clarity is critical, some technicians favor a small percentage of glycerin (1–2%) in water to slightly thicken the film, enhancing lubrication without significantly slowing cut. Always test on a panel; too much viscosity can float the sheet and round edges.

Water temperature alters backing behavior. Cool water (10–15°C / 50–59°F) keeps the resin bond firm and reduces over-softening on paper-backed sheets. Warm water (20–30°C / 68–86°F) can make stiff papers more compliant but risks accelerating hydrolysis on budget bonds. For most workflows, room-temperature water is ideal. Keep a second rinse bottle with distilled water to flush panels—especially on dark automotive finishes—so minerals don’t dry into the surface and mask scratch visibility.

Anti-foam agents aren’t typically necessary; excessive suds hide defects. Likewise, avoid silicone-containing lubricants in finishing environments; they can cause fisheyes in any subsequent coating step. On bare metals, add a corrosion inhibitor or wipe often and dry thoroughly; water sitting under slurry can flash-rust quickly.

- Mix ratio baseline: 1 liter clean water + 2–3 drops mild dish soap. For film-backed micro-abrasives, consider straight distilled water for more direct feedback.

- Refresh cadence: Replace the pan every 15–20 minutes or when slurry darkens; a dark bath reduces cut efficiency and scratch visibility.

- Clean-room habits: Dedicated squeeze bottles for each grit step minimize cross-contamination and allow precise spot flushing.

According to a article.

Grit Progressions and Slurry Management

Soak time is the prelude; grit sequencing and slurry control are the composition. For leveling work on clear coats or varnish, a common progression is P800 → P1200 → P1500 → P2000 (then compounds). On wood finishes that are relatively soft compared to automotive urethanes, consider starting at P1000 to avoid over-aggressive leveling. Each step should remove 100% of the previous scratch pattern before moving on; don’t chase speed at the cost of deep defects that survive to polishing.

Slurry is both friend and foe. As grains fracture, they shed fine particles that blend with water into a cutting paste of effectively higher grit. The first dozen strokes of a fresh sheet are the most aggressive; as slurry builds, the cut refines. Use this to your advantage: initial leveling with slightly lower lubrication (just wet) to establish plane, then increase fluid and lighten pressure to transition the scratch to a polish-ready state. If the sheet begins to skate, you’ve over-lubricated—wipe, re-wet lightly, and resume.

Slurry management techniques:

- Wipe windows: Every 6–10 passes, stop and squeegee the surface with a clean rubber blade, then inspect under raking light. Rinse the sheet against the bucket wall to dislodge embedded swarf.

- Two-bucket method: One for clean water, one as a dirty rinse. Dip the sheet in dirty first, wipe on a grit guard or mesh, then reload in clean water before returning to the panel.

- Edge discipline: Avoid sanding off the edge into space; edges concentrate pressure and can peel grain. Use an interface pad with a slightly rounded edge and lighten your stroke at boundaries.

- Mark-and-clear: Lightly Sharpie the target area before the first pass; when the ink is uniformly gone at the current grit, you’ve leveled that pass.

Progress by reduction ratios rather than fixed grit jumps: aim for 30–50% reductions in average particle size. For example, P1000 to P1500 is roughly a 33% change; P1500 to P2000 is ~25%. This moderates the removal depth needed at each step and preserves topcoat thickness.

Workflows by Material and Use Case

Automotive clear coats

Objective: flatten orange peel and nibs while preserving film build. Start with P1200 or P1500 on a firm foam interface block. Soak waterproof paper 5–10 minutes; film-backed sheets 1–3 minutes. Use cool to room-temperature water with a drop of soap per liter. Maintain light, even strokes, and monitor with a guide coat or raking LED. Move to P2000 and then P3000–P5000 film-backed discs or sheets before compound. Dry thoroughly between steps; water can disguise residual scratches that become obvious once buffing heats and swells the clear.

Wood finishes (lacquer, varnish, polyurethane)

Objective: level dust nibs and telegraphed grain without cutting through. Because finishes are softer, begin at P1000–P1500, paper-backed sheets soaked 5–10 minutes for flexibility. Add a few drops of soap; avoid heavy glycerin which can over-lubricate and slow the bite you need for leveling. Use a soft interface pad to bridge pores on open-grain woods. Wipe often and check under angled light; if an area warms or gets tacky, pause. Thin finishes can burn through quickly at edges.

Metals (aluminum, stainless, tool steel)

Objective: refine to a brushed or mirror finish while controlling heat and corrosion. Start at P600–P800 depending on the baseline, with 5–10 minute soaked paper-backed sheets. For mirror pre-polish, shift to film-backed P1500–P3000. Use distilled water and consider adding a corrosion inhibitor when working ferrous alloys, or dry and oil between steps. Pressure should be minimal—let slurry do the work. Drying streaks can hide micro-scratches; always final-rinse and wipe with lint-free cloth before deciding to step up.

Plastics and composites (acrylic, polycarbonate, resin casts, gelcoat)

Objective: remove tooling marks or achieve optical clarity without stress-cracking. Start finer (P1000–P1500) with 1–3 minute pre-wet film-backed sheets to avoid deep gouges. Keep water cool—warm water can soften plastics and change scratch response. On gelcoat, P800–P1200 is acceptable for leveling, but monitor carefully. Avoid aggressive edges and point loads; use a foam pad and broad contact.

Shop reality checks

- When a sheet starts to chatter, it’s usually a boundary condition—too dry, too much pressure, or grit loaded. Refresh water, lighten pressure, and flex the sheet to shed slurry.

- If a sheet edges sheds grit, shorten soak time and transition to film-backed for finishing steps.

- Always measure removal risk: on clear coats, track thickness with a paint depth gauge; on wood finishes, count passes and pressure.

Troubleshooting and Quality Control

Defects during wet sanding usually trace back to four variables: sheet condition, lubrication level, pressure control, and contamination. A disciplined approach isolates each.

- Random deep scratches (RDS): Often caused by debris trapped under the sheet or a rogue larger grit. Solution: increase rinse frequency, dedicate separate trays and bottles to each grit, and inspect sheets under light before use. If RDS appear, step back one grit and re-level the area before proceeding.

- Haze that won’t polish out: Over-lubrication can float the sheet, dulling the surface with a smeared micro-scratch rather than a clean cut. Reduce soap concentration, dry-wipe to reset, and make a few passes with fresh sheet and minimal fluid.

- Edge burn-through: Excess pressure at boundaries or hard blocks. Switch to a softer interface pad, bevel your strokes before edges, and feather pressure on the last inch of travel.

- Premature sheet failure: Over-soaking or high-temperature water can weaken bonds. Stick to the 5–15 minute window for paper-backed sheets, 1–3 minutes for film-backed, and room-temperature water.

- Persistent loading: On softer finishes, slurry can gum, especially with heat. Cool the panel, reduce pressure, and reintroduce a small amount of surfactant. For wood finishes, ensure the film has fully cured; soft finishes load even in wet workflows.

A quick quality control ladder improves outcomes:

- Prep light: raking LED at 30–45 degrees to reveal topography.

- Mark the area: pencil or guide coat to track leveling.

- Stroke count: 10–15 consistent passes before reassessment, not indefinite scrubbing.

- Inspect dry: wipe and check—water hides defects.

- Log settings: grit, soak time, additives, pressure feel. Repeatability turns craft into process.

Wet Sanding Wood — Video Guide

Brad’s tutorial on wet sanding wood walks through the essentials of taking a wooden surface from leveled to silky using water-lubricated abrasives. He demonstrates how to manage slurry, choose the right block, and sequence grits so the finish lays flat without cutting through.

Video source: Wet Sanding Wood for a Smooth Finish

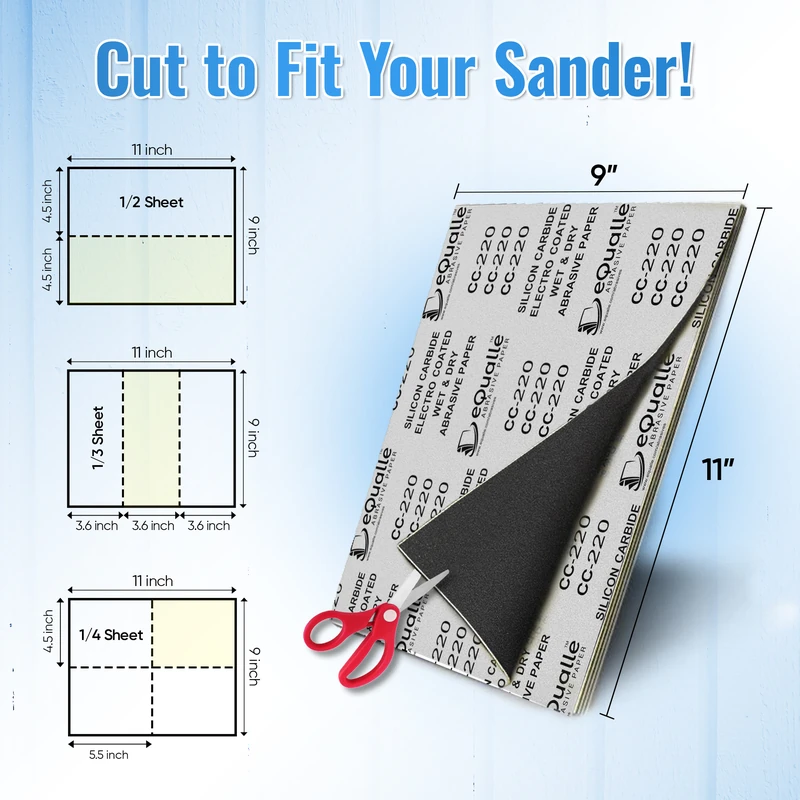

280 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (25-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Fine finishing grit for delicate work—ideal for flattening varnish layers and creating a pre-polish smoothness on wood or resin. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: How long should I soak wet dry sandpaper for automotive clear coats?

A: For modern waterproof paper, 5–10 minutes is ideal; for film-backed finishing sheets (P3000–P5000), 1–3 minutes is sufficient. Avoid long soaks that can weaken sheet edges.

Q: Is it safe to add soap to my sanding water?

A: Yes. Add 2–3 drops of a mild, non-silicone dish soap per liter to reduce surface tension and improve lubrication. Avoid heavy suds and silicone additives that can contaminate finishes.

Q: Can I soak sheets overnight to make them more flexible?

A: It’s not recommended. Extended soaking can soften resin bonds and cause grit shedding, especially at the edges. Use a 5–15 minute soak for paper-backed sheets and a 1–3 minute pre-wet for film-backed abrasives.

Q: Why does my paper curl or crack when folded after soaking?

A: Under-soaking leaves fibers stiff, and folding can fracture the resin. Increase soak time slightly (by 3–5 minutes) and ensure water is at room temperature. If cracking persists, switch to a more flexible backing or a higher-quality sheet.

Q: How should I store pre-soaked sheets between steps?

A: Don’t. Use them within the session, keeping them submerged in clean water trays. If you must pause, lay sheets flat on a non-absorbent surface and re-wet before resuming. Dry storage after soaking can warp paper and degrade bonds.