Furniture Restoration: Fixing Chipped and Lifting Veneer

Saturday morning, shop lights warm, coffee cooling on the bench. I slide a hand over a walnut dresser that’s outlived two generations. It has presence—clean lines, true drawers, the kind of proportions you can’t fake—but the veneer tells a rougher story. One front edge is chipped back to the substrate. A corner has lifted into a sharp little tent. Water once sat beneath a pot, raising a blister the size of a thumb. You could pass this piece over at a thrift store and never know what it could become. Or you can see it for what it is: a solid candidate for furniture restoration with a few smart, careful veneer repairs.

I’ve been in this moment countless times with clients’ pieces and my own finds. Veneer scares people because it feels delicate and mysterious. In reality, veneer is just wood—thin, yes, but strong when bonded right, and surprisingly forgiving if you understand how it behaves. Lifting veneer is rarely a death sentence; it’s usually a glue failure. Chips can be patched invisibly with patience and grain awareness. And sanding, the most feared step, is manageable with a block, restraint, and a plan.

The trick is methodical work. Diagnose, stabilize, then move forward with repair before any refinishing. If you sand or strip first, damaged veneer will tear and spread. Start with glue, clamping strategy, and grain-matched patches. Then we’ll level, sand, and prep for color so the finish blends like it never happened. In this guide, I’ll walk you through my bench-tested process for lifting and chipped veneer, including glue selection, clamping cauls, patch fitting, and real-world sanding techniques that won’t burn through. If you’re looking to bring a piece back to life without replacing all its history, pull up a stool—this is how we do it right.

Quick Summary: Stabilize loose veneer with the right glue and clamping, patch chips with grain-matched pieces, then sand and finish carefully to make the repair vanish.

Diagnose the Veneer and Substrate

Before you touch a scraper or sander, figure out what you’re standing on. Veneer is thin—often 1/28"–1/40"—and its survival depends entirely on the bond below it. Your first job is to map what’s loose, what’s missing, and what’s holding tight.

Start with a bright raking light and your fingertips. Mark lifted areas with painter’s tape. Tap around bubbles with the plastic end of a screwdriver: a hollow tap usually means delamination, while a solid thud says the bond’s intact. Gently ease a thin palette knife or feeler gauge under any lifted edges to check how far the failure travels. Don’t force it—if the blade binds, stop. This isn’t the time to make damage bigger.

Identify the substrate. Older pieces often use solid wood cores or stable plywood; mid-century and later furniture might use particleboard or MDF. Particleboard that has swelled from water can crumble; MDF is more uniform but drinks moisture at edges. If the core is shot, plan to consolidate it with thin epoxy or replace sections before re-gluing veneer.

Note contamination. Old finish, hide glue crystals, and dust all interfere with adhesion. If you’re re-gluing through a narrow opening, you’ll need to clear debris with compressed air, vacuum, or a sliver of sandpaper wrapped around the palette knife. For bubbled veneer, confirm whether it’s torn. If the veneer layer itself is cracked, you’ll stabilize both the crack and the bond.

Finally, assess moisture. Veneer bubbles from steam or plant leaks sometimes flatten when fully dry. If you suspect recent moisture, give the piece 24–48 hours in a controlled shop environment before committing to glue. Stabilize first, refinish second. That decision saves time and material every single time.

Tools, Adhesives, and Shop Setup

Good repairs start with the right gear laid out on the bench. Think small, precise, and controlled—this isn’t a framing job, it’s surgery.

Core tools:

- Palettes knives, thin putty knives, and feeler gauges for probing and glue delivery

- Glue syringes and blunt needles (18–20 gauge) for precise injection

- Wax paper, parchment, and packing tape for nonstick barriers

- Hardwood cauls, cork/rubber pads, and a spread of clamps or heavy flat weights

- Card scraper, sanding blocks, 180–320 grit paper, and a sharp utility knife

- Veneer saw and a small shooting board for patch fitting

- Heat gun or clothes iron with a pressing cloth for relaxing veneer

Adhesives: choose based on reversibility, open time, and gap-filling.

- Hot hide glue: period-correct, reversible with heat and moisture, tacks fast. Great for antiques and where future repairs matter.

- PVA (yellow wood glue): reliable, strong, and widely available. Use a fresh bottle; thin slightly with water (up to 5%) for injection if needed.

- Liquid hide glue: convenient, long open time, still reversible. Good compromise for hobby shops.

- Epoxy: gap-filling and stabilizing rotten substrate; use sparingly and avoid squeeze-through that prevents future repairs.

- CA (cyanoacrylate): spot-fixes tiny edge chips and stabilizes hairline cracks; pair with wood dust for color.

Shop setup matters. You want stable temperature (65–75°F) and moderate humidity. Have plenty of cauls ready, shaped to the area you’ll press. Curved drawer fronts may need custom cauls—trace the curve and plane a matching block. Wrap cauls in packing tape to prevent sticking. Test clamp pressure on dry runs so you can move fast once glue is in.

Pro Tips:

- Warm the area with a heat gun or iron before injecting glue; warm wood flows glue better.

- Keep alcohol wipes ready to clean squeeze-out, especially with hide glue.

- Mark clamping positions with tape so you can land clamps fast and even.

- For thin veneers, add a cork pad to distribute pressure and avoid telegraphing clamp marks.

- Label syringes for each glue type and don’t cross-use; cured residue ruins tips.

Gluing Lifted Veneer for Furniture Restoration

When you’ve mapped the loose zones, it’s time to bond them for good—without swelling the veneer or starving the joint. Here’s the process I use on nearly every lifting repair.

Dry rehearsal. Place cauls and clamps, check reach, and pad curved areas. Mark clamp spots with tape. Pre-cut wax paper to size.

Open and clean. Gently lift the veneer with a palette knife. Clear dust and old glue granules with a straw on your shop vac or a puff of compressed air. If the veneer is brittle, soften it with gentle heat; an iron on low, through a cotton cloth, works well.

Glue choice. For antiques or pieces you might revisit, use hot or liquid hide glue. For modern work, fresh PVA works great. If the substrate is crumbly, brush in thin epoxy to consolidate, let it gel, then use PVA or hide glue for the veneer bond.

Inject and spread. Load a syringe, then inject glue deep under the veneer, working from the farthest point back toward the entry. Use the palette knife to squeegee glue evenly. You want full coverage, no puddles.

Clamp smart. Barrier with wax paper. Use flat hardwood cauls with even clamp spacing. Start from the center and work out. Too much pressure can starve the joint; aim for firm, even pressure that presses the veneer flat without wrinkling.

Clean squeeze-out. With hide glue, warm water on a cloth cleans easily. With PVA, use a barely damp cloth and be careful—don’t soak veneer. Pick dried squeeze-out with a sharp chisel later if needed.

Cure time. Leave it alone. Give PVA 8–12 hours and hide glue enough time to cool and set. Remove clamps, check bond, repeat for adjacent sections if necessary.

If the veneer is cracked but present, bridge the crack with glue, then clamp until flush. A card scraper later will level micro ridges without thinning the field. And for nausea-inducing bubbles, a small relief slit along the grain lets you inject glue where you need it, then close the cut under caul pressure. Italic note from the field: According to a article, lifting and cracked veneer can often be saved with careful re-gluing rather than full replacement—exactly what we’re doing here.

Patching Chips and Missing Corners

When wood is gone, don’t guess—patch it with matching veneer. A tight, grain-aligned patch blends better than any filler and stands up to finishing.

First, source veneer. Ideally, pull a donor from a hidden section of the same piece (back edge or internal surface) to ensure perfect species and figure. If that’s not possible, select a sheet that matches color and grain direction; quartered veneer won’t pass for flat-sawn and vice versa.

Prepare the cavity. Square the damaged area with a sharp knife guided by a small straightedge, or cut a shallow, tapered “scarf” patch shape that increases glue surface. Keep edges crisp and cut with the grain. For corner breaks, rebuild the missing substrate with a structural epoxy putty, sand it to the correct profile, then apply veneer over it.

Cut the patch slightly oversize, aligning grain flow and any figure. Use a veneer saw or knife on a cutting mat. Dry-fit and adjust. For Dutchman-style repairs, tape the patch in place and knife through both layers (patch and existing veneer) to achieve a perfect mate line. Label the patch orientation so it goes back exactly.

Glue with your chosen adhesive, barrier with wax paper, and clamp under a flat caul. Light pressure is enough for thin patches—don’t squeeze all the glue out. Once cured, slice proud edges with a sharp chisel bevel-down, then scrape and block sand until flush.

For tiny losses at edges, wick thin CA into the chip, then dust with matching wood flour and tap it in. Scrape once cured. This trick disappears on dark woods and edge banding.

Color comes later, but keep this in mind: a perfect mechanical fit beats any stain trick. If your eye can’t find the joint in raw wood, you’ll win after finishing.

Level, Sand, and Prep for Finish

This is where most veneer projects are won or lost. Veneer doesn’t forgive aggressive sanding. Think sharp, flat, and measured.

Start with leveling. Use a tuned card scraper to bring repaired zones down to the surrounding surface. Hold the scraper slightly bowed, burnish the edge, and work with the grain. You’ll feel when patches are flush. Scrapers remove high spots without dipping like soft sanding pads do.

When you do sand, use a rigid block. I start at 180 or 220 grit for veneer; 120 is too risky unless your surface is very uneven and you’re skilled with a block. Pencil a light grid on the surface and sand until the marks just vanish—that’s your guide coat. No power sanding on edges, and be very careful with random orbitals; if you use one, add a hard interface pad and keep it moving lightly.

Treat edges as sacred. Tape a 1/8" safety border along edges and corners; finish those by hand later with only a few strokes. Most burn-throughs happen on edges and convex curves. On bubbly zones you re-glued, sand only after full cure.

Vacuum thoroughly between grits. I like a quick wipe with mineral spirits at this stage to preview the grain and detect low spots; let it flash completely before proceeding. If the veneer pores are open and you want a glassy mid-century finish, consider a grain filler. Apply with a plastic spreader, pack it across the grain, and scrape off the excess. Sand lightly once cured.

Seal smart. A 1–2 lb cut of shellac as a wash coat locks down any stray glue residue and evens absorption before stain or toner. It also provides a safe barrier if you’ll be using water-based products over old oil-based residues. Keep everything flat and controlled—this is prep, not a race.

Color, Grain, and Topcoat Matching

Make your repairs disappear by controlling color in layers. Don’t try to do all the work with one heavy stain.

Start with dye if you need to shift the base tone. Water- or alcohol-based dye penetrates veneer evenly and can nudge a patch toward the field color. Test on scrap veneer from the same sheet you used for the patch; adjust concentration, not saturation, to sneak up on the right hue.

Next, judicious pigment stain can add body and highlight grain. Wipe on, wipe off, and watch the contrast—too much pigment sits in the pores and reveals repairs. If the field wood has aged amber while your patch is fresh, a light amber shellac wash before staining can pre-age the new veneer.

For fine blending, use toners: clear finish with a dash of dye or pigment sprayed lightly. Two or three mist coats can harmonize a slightly off-color patch without muddying the grain. If you don’t spray, aerosol toners are a shop-friendly option for small areas. Keep the can moving and build gradually.

Choose topcoat for use and era. A mid-century dresser loves a filled, satin lacquer or waterborne conversion varnish; a traditional piece can sing under shellac and wax. Oil-modified urethane is tough but can amber too much for some veneers—decide based on the look you want. Match sheen precisely; a satin patch on a semi-gloss surface will stand out even if the color is perfect.

Between coats, de-nib with a gray pad or 320 grit on a block, always with a light hand. If a patch still whispers, a final toner pass before the last coat is your invisibility cloak. Patience here pays—repairs vanish not by magic, but by controlled, cumulative steps.

The WORST veneer — Video Guide

If you want to see a real “worst-case” veneer situation, there’s a video where a maker takes on a dresser with veneer so damaged it looked beyond hope. He walks through diagnosing what can be saved, when to replace entire sections, and how to manage brittle, fractured sheets without turning them into confetti.

Video source: The WORST veneer I've ever worked on... Furniture Restoration

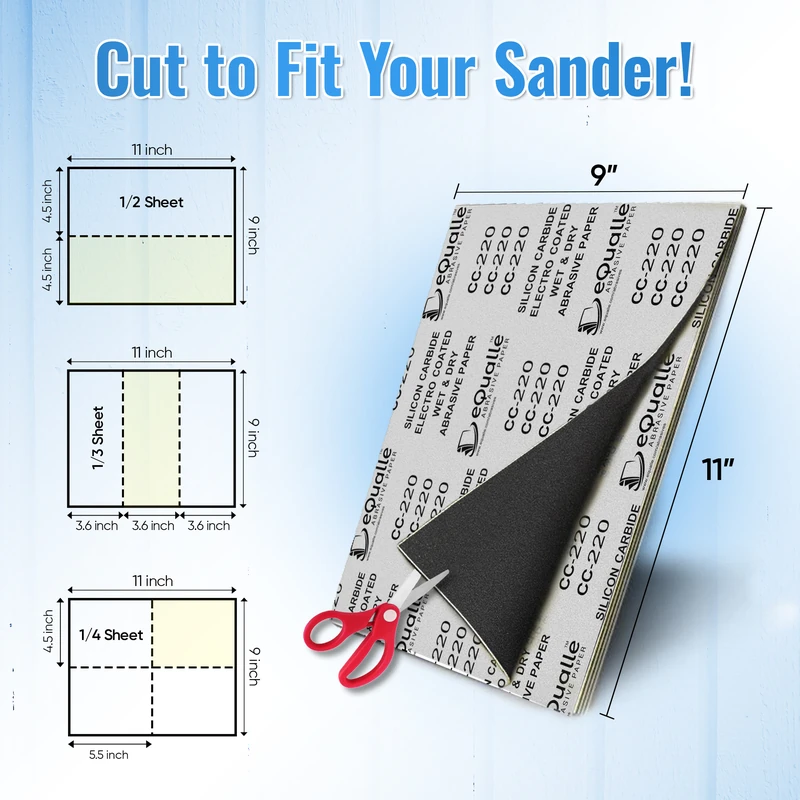

1000 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (10-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Gentle polishing grit that removes swirl marks and fine scratches on automotive or resin finishes. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Can I re-glue lifting veneer without stripping the finish first?

A: Yes. Carefully inject glue under the loose area, clamp with cauls, and clean squeeze-out. Strip or sand only after the bond is solid.

Q: What’s the best glue for antique veneer repairs?

A: Hot hide glue (or liquid hide) is ideal—strong, reversible, and period-appropriate. It makes future repairs easier than PVA.

Q: How do I fix a water bubble that flattened after drying?

A: If it stays flat, leave it. If it reappears with pressure, inject glue through a small slit with the grain, clamp flat, and let it cure fully.

Q: I’m afraid of sanding through—what grit should I start with?

A: Begin at 180–220 with a hard block and rely on a sharp card scraper for leveling. Avoid power sanding near edges and corners.

Q: What if the particleboard substrate is crumbling?

A: Consolidate with thin epoxy, let it cure, then re-glue the veneer. For badly degraded areas, replace the substrate section before patching.