Molding sanding: keep crown profiles crisp

On a quiet Saturday morning, you finally pull the drop cloths over your living room floor and tilt a lamp toward the ceiling. The crown molding looks elegant from a distance, but up close the paint has chipped at the corners and the once-crisp beads have gone a little blurry. You run a fingertip along a cove that should feel like a clean arc, and instead it’s a soft bump. That’s the moment when most DIYers decide to sand—and the moment many profiles lose their sharp character. The goal isn’t to erase the molding’s shape; it’s to refine the surface. With a thoughtful approach to molding sanding, you can keep each flare, bead, and cove true while preparing for a flawless new finish.

Sanding crown is different from sanding a flat board. The curves change the way pressure concentrates, and the wrong abrasive can “iron out” the details. If you’ve ever finished a room and noticed that light raking across the ceiling emphasizes flattened spots, you know the heart-sink that follows. The fix isn’t to avoid sanding; it’s to switch to tools and techniques designed for curved surfaces. Whether you’re repainting a whole room or touching up a single run, the right strategy will help you maintain crisp relief, continuous lines, and tight transitions at corners.

This guide balances craft and practicality. We’ll cover how profiles flatten, what tools truly fit the geometry, and how to sand with just enough pressure to refine the surface—not reshape it. We’ll also walk through prep and finishing, so your effort shows in the final coat rather than in missing details. If you’re careful, you’ll end the day with molding that looks like it just came off the molder—only smoother.

Quick Summary: Use shaped backers, fine grits, light pressure, and short, profile-following strokes to sand crown molding without flattening its details.

Why profiles go flat

Crown molding flattens for a simple reason: pressure and contact area. When you press a flat abrasive against a curved bead, only the highest point touches. That tiny contact patch takes all your force, cutting fast and rounding over edges. Foam sponges reduce the severity but still compress, spreading pressure into places it doesn’t belong. Over a few passes, a crisp quirk becomes a softened groove—especially on painted pine or MDF where fibers yield quickly.

Abrasive stiffness matters too. Paper backed with your fingers will drape over a cove, creating a flexible but uneven surface that sands peaks first. Hard blocks keep edges crisp on flats but bridge over hollows, sanding peaks and skipping valleys—exactly the recipe for flattening a profile. Even grit choice contributes; coarse grits scratch deeply, and the scratches need more sanding to remove, compounding the risk.

Technique plays an equally important role. Long back-and-forth strokes across multiple features blend the highs and lows together. Pushing across grain or lingering at transitions (like where a cove meets a fillet) erases the crisp line your eye uses to read the shape. Rushing through prep compounds the problem; heavy primer or filler left proud of the surface forces more sanding later—again, right where details are most vulnerable.

Once you see how quickly pressure concentrates on curves, the solution becomes clear: match the abrasive’s shape to the profile, reduce pressure, and limit your contact to the area you intend to refine.

Choosing tools for molding sanding

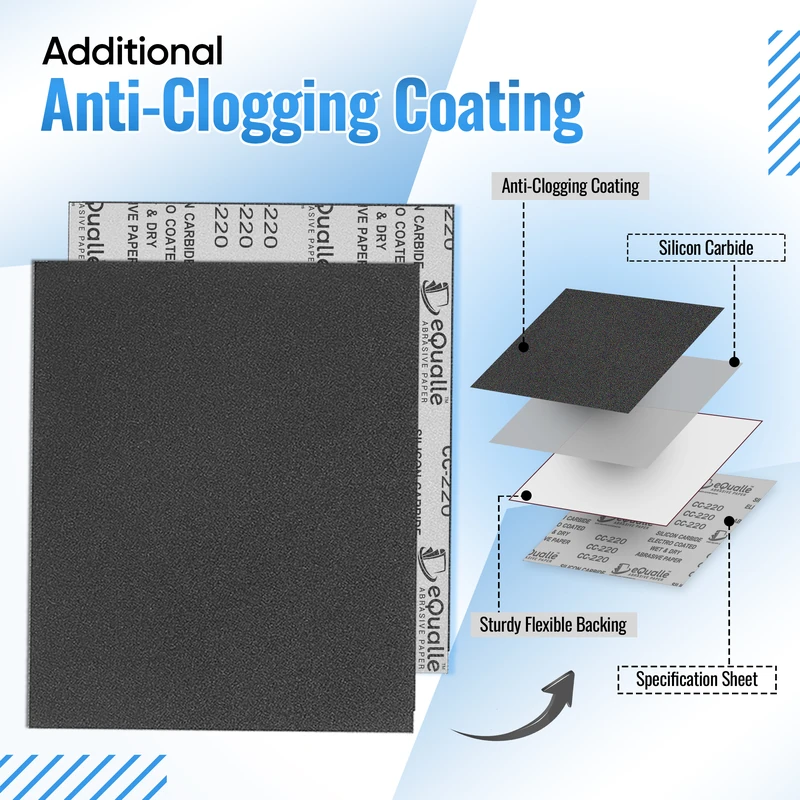

Start with abrasives that conform without collapsing. Foam-backed sheets (1/8–1/4 in. thick) paired with a soft interface pad give you control while keeping pressure even. Mesh abrasives (like open-coat, dust-extracting varieties) resist clogging, which means you can use lighter pressure for longer. For delicate edges, micro-abrasive pads in 320–600 grit help burnish without cutting aggressively.

Shaped backers are the real heroes. The best option is a custom sanding block that mirrors your crown’s profile. You can make one from a short offcut of the same molding: wrap it in packing tape or plastic wrap, lay adhesive-backed paper over the working face, and rub gently along the installed molding. The paper sits exactly where the original cutter did, preserving arcs and beads. Rubber profile blocks and art erasers also work as quick, flexible backers for coves and fillets; they distribute pressure while staying within the feature.

Power tools have a place, but choose them carefully. A random-orbit sander flattens profiles—save it for flat fascia or baseboards. If you must use power, a detail sander with a soft interface and very light touch can help on broader concaves, but hand control is usually safer. Small sanding sticks (think hobby-grade sticks with replaceable paper) excel in tight quirks and beads. For production settings or long runs pre-install, a molding sander with profiled heads is ideal, but that’s beyond most home projects.

Finally, set your grit progression to minimize material removal: 180 to 220 for scuff-sanding existing paint, 220 to 320 for between-coat leveling, and up to 400+ for final nib removal on high-gloss finishes. The right grit reduces passes, which protects the profile.

Techniques that preserve the profile

The technique is where profiles live or die. The guiding rule: sand the exact shape, no more and no less. That means limiting your contact area, letting the abrasive do the work, and using strokes that trace the grain and curvature.

- Use a “guide coat” pencil: Lightly scribble a soft pencil across the surface. Sand until the marks just disappear in each feature. If pencil remains in a valley, switch to a smaller, shaped backer rather than pushing harder.

- Pull, don’t push, on edges: When refining a bead, pull the shaped block along the grain with minimal pressure. Pushing tends to dig into the far edge at the end of the stroke.

- Break it into features: Sand beads, coves, and flats separately with backers that match each. Avoid strokes that cross a transition line; protect fillets by masking them with a strip of low-tack tape if needed.

- Keep strokes short: Work in 6–10 inch sections, finishing each to a consistent scratch pattern before moving on. Overlapping lightly maintains continuity without flattening.

- Reset often: Clean your abrasive with a rubber belt cleaner or tap to release dust. A loaded abrasive forces more pressure and heat, which dulls details.

For many profiles, a simple custom backer changes everything. Wrap a 6–8 inch piece of your crown in plastic wrap, press a layer of two-part filler or hot-melt glue onto a scrap block, and while it’s soft, press it gently against the wrapped molding. Once cured, peel off the wrap: you have a perfect negative that supports the paper right where it should cut. Use PSA (pressure-sensitive adhesive) paper or wrap strips around the form. You’ll feel how much less pressure you need, and you’ll avoid bridging over hollows.

According to a article, shaping a sanding block to match curves prevents the “flattening” effect by keeping pressure distributed across the contour rather than concentrated at the high points. This confirms what you’ll experience in practice: the right backer is the safest way to refine without reshaping.

Prep and finishing details

Good results start before you sand. For paint-grade molding, remove loose paint and caulk first. Score failed caulk lines with a sharp knife, pull them cleanly, and vacuum dust from the profile. Fill nail holes and dings with a lightweight, non-shrinking filler; overfill slightly so you can level without touching surrounding details. Let it cure fully—rushing forces more sanding.

Scuff-sand existing finishes with 180–220 grit on matched backers. You’re aiming to dull the sheen and knock down nibs, not to level the surface flat. Use raking light (a work light held low to the surface) to spot high spots or shiny patches that need another pass. After sanding, vacuum thoroughly and wipe with a damp microfiber cloth to pick up fine dust without soaking the wood or MDF.

A sealing primer stabilizes fibers and reduces fuzzing during further sanding. On old oil paint or stained wood, a shellac-based primer grips reliably and dries hard, making it easier to sand lightly with 220–320 without smearing. On MDF, avoid over-wetting; seal early to prevent the paper face from swelling. After the first primer coat, use your shaped backers to feather any filler and knock down raised grain. Keep strokes localized and light.

Between coats of finish, switch to ultra-fine abrasives (320–400 or a gray non-woven pad) and use the lightest possible pressure. You’re just eliminating dust nibs and minor texture. Wipe down with a tack cloth or clean microfiber before recoating. The reward for restraint is a topcoat that reads every crisp line and curve, lit cleanly by room light with no mushy geometry.

Troubleshooting and repairs

If you notice flattened areas, all is not lost. First, identify whether you’ve rounded a bead, flattened a cove, or softened a quirk line. Then choose a targeted fix rather than more general sanding.

- Flattened bead: Create or use a concave backer that matches the bead’s radius. Pencil a guide coat and sand only the bead until the line is re-established. If wood has been removed too far on one side, a tiny amount of high-build primer or lightweight filler can rebuild the contour on paint-grade work; sand carefully to blend.

- Hollowed cove: Use a convex backer (a dowel wrapped in paper, ideally with a radius close to the cove) to even the surface. Work with light strokes and avoid crossing onto adjacent fillets. A flexible rubber hose wrapped in paper can fit a range of concaves.

- Lost quirk line: Score the line lightly with a marking knife to re-define the boundary, then sand up to—but not over—the score with a shaped backer. The knife line acts as a hard stop and visual guide under primer.

- Over-sanded MDF: MDF edges fuzz and round rapidly. Seal with shellac, let dry, and sand with 320 on a shaped backer. Repeat if needed. Avoid water-based primers for the first coat on raw MDF edges.

For more significant damage on paint-grade crown, epoxy putty can rebuild missing details. Shape it while green with a custom tool (a scrap shaped to the profile), then sand lightly after cure with your matched backer. Stain-grade repairs are trickier; consider replacing a short section or using colored wax sticks and careful blending. For inside and outside corners, dry-fit a small template to maintain crisp transitions; a clean corner is where the eye lingers, so prioritize re-establishing that geometry even if small sections elsewhere remain slightly softened.

As always, dust control helps your eye see what’s really happening. Vacuum frequently and use raking light. If you can watch the scratch pattern and the highlights, you can stop at the right moment—before flattening creeps in.

Changing The Sanding — Video Guide

If you’re working in a shop setting or handling long runs pre-installation, understanding how a molding sander’s head changes the cut is valuable. In a concise demo, a woodworker shows how to remove and replace the sanding head on a dedicated molding machine, highlighting the alignment and safety checks that keep profiles accurate.

Video source: Changing The Sanding Head On The Molding Master, How To! EthAnswers

320 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (50-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Fine finishing grit for sanding between coats of paint, primer, or lacquer. Provides smooth, even results for woodworking, automotive, and precision finishing. Works efficiently for wet or dry applications. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What grit should I use to scuff-sand pre-painted crown?

A: Start with 180–220 grit on a shaped or foam-backed pad to dull the sheen and remove nibs. Avoid coarser grits unless you’re removing defects; they cut too aggressively and risk flattening details.

Q: How do I sand the tiny quirk between a cove and a fillet without rounding it?

A: Use a slim sanding stick or fold a strip of 320–400 grit around a thin, firm backer (like a plastic card). Work only within the quirk, using short, light strokes along the grain, and stop as soon as pencil guide marks disappear.

Q: Can I use a random-orbit sander on crown molding?

A: Not on the profiles. A random-orbit sander will flatten curves and roll edges quickly. Reserve it for adjacent flat trim boards; for crown profiles, use hand sanding with shaped backers or a detail sander with a soft interface and a very gentle touch.

Q: What’s the best way to make a custom sanding block for my crown?

A: Press a soft medium (hot-melt glue, two-part filler, or silicone) against a plastic-wrapped offcut of your molding to create a negative. Once cured, wrap with PSA paper or clamp paper to it. This matches the exact geometry and prevents flattening.

Q: Should I sand between primer and topcoats on molding?

A: Yes, but lightly. After primer, use 220–320 grit on matched backers to knock down raised grain and filler. Between topcoats, use 320–400 grit or a non-woven pad to remove nibs without altering the profile. Clean thoroughly before recoating.