Rust Repair: Spotting Surface, Scale, and Perforation

Saturday morning light caught the fender of my old wagon just right, the way it sometimes does when you’re not quite awake and not quite rushing. A faint blister under the paint telegraphed something I’ve learned to notice: the subtle topography of oxidation. It’s the kind of moment most of us meet with a sigh and a glance away. I paused instead. As a product engineer who’s spent years testing abrasives, primers, and coatings, I’ve learned that the difference between a quick cosmetic tune-up and a structural failure starts with how we look at rust—and how early we decide to act on it. Whether you wrench on weekends or you’re planning a professional rust repair, the first step is classification. Is it only surface rust that can be abraded clean? Is it scale that has undermined the steel layers? Or is it perforation where oxygen and time have already won a hole through the sheet?

The distinction isn’t just vocabulary. Each stage responds to different tools, different grits, different binders in abrasives, and different chemistry in primers and rust converters. The wrong choice wastes time and heats metal unnecessarily; the right choice preserves thickness, integrity, and cost. In the lab, I measure cut rates, heat generation, and residual profile with objective tools. In the driveway, you can do the same—just scaled down and simplified. This article shares a practical, test-driven method to identify surface rust versus scale and perforation, then match your approach to the stage. If you’ve ever wondered when you can sand and seal versus when you must cut and replace, this will give you a clear, engineering-grade path to decision-making and better rust repair outcomes.

Quick Summary: Learn to classify corrosion by sight, sound, and thickness, then pick the right abrasives, chemistry, and repair method to stop rust at the root.

How steel fails: film, surface, scale, holes

Corrosion in mild steel is a progression, not a switch. At the earliest stage, you may see a uniform orange tint or fine speckling—flash rust—often forming within minutes after bare metal sees moisture and oxygen. This is a thin oxide film that hasn’t yet undermined the metal’s structure. A grey Scotch-Brite–style nonwoven pad or 320–400 grit aluminum oxide paper typically erases it without changing panel thickness, leaving a faint profile ready for epoxy primer.

Move one notch deeper and you find surface rust. Here, the oxide layer has gained thickness and porosity, but the base metal remains continuous. You’ll see matte orange-brown with slight roughness. Under a scribe, it powders off. A flat blade or pick won’t easily sink into the steel beneath; instead, the rust crumbles. Abrasively, 120–180 grit aluminum oxide or silicon carbide cuts efficiently. The key metric: after cleaning, the panel still rings when tapped and measures near original thickness with a caliper at the edge or an ultrasonic gauge if you have one.

Scale rust is the turning point. The oxide has stratified—think laminated layers—often with dark brown to black areas (magnetite and hematite) and lifting paint edges. Here, a screwdriver can delaminate flakes. A hammer tap yields a duller thud, signaling loss of stiffness. Mechanically, scale resists fine papers; it responds better to more aggressive abrasives (e.g., zirconia flap discs) or impact tools like a needle scaler. Expect pitting: when you remove the scale, you’ll find craters you can feel with a fingernail.

Perforation is the endpoint: through-holes, bubbling that collapses under light pressure, and rust bridging seams from the inside out. Tap-testing reveals a papery, dead sound; a pick may penetrate. The remaining metal often has razor-thin edges. At this stage, patching with filler is cosmetic only; structural integrity requires cutting back to sound metal and welding or a proper mechanical fastening method for non-structural panels.

Simple tests to classify rust

You don’t need a lab to tell surface rust from scale and perforation; you need consistency. I rely on four field tests: visual magnification, pick-and-scrape, tap acoustics, and thickness checks.

Visual and magnified inspection: Wipe the area clean with isopropyl alcohol to remove oils. Use a bright LED at a low angle and a 3–5x magnifier. Surface rust shows uniform coloration and fine grain; scale reveals lift points, darkened islands, and undercut paint edges. Blisters near seams suggest corrosion from the back side.

Pick-and-scrape test: With a sharp scribe or awl, press at 45 degrees. Surface rust powders and reveals bright metal quickly. Scale delaminates in flakes; you’ll feel steps as layers lift. If the pick breaks through with modest pressure, you’re at or near perforation. A stiff putty knife can also pry at edges; look for how far the rust propagates under paint—this indicates the zone you must chase.

Tap acoustics: Using a small ball-peen hammer or even the plastic handle of a screwdriver, tap from known good metal toward the suspect zone. Listen for the transition from a crisp ring to a dull thud. Mark the boundary with tape. Thin, undermined steel lowers audible frequency; the ring test is surprisingly reliable with a little practice.

Thickness and deflection: At panel edges where you can access bare steel, measure with a micrometer to estimate factory thickness (often 0.7–1.0 mm for many body panels). If available, an ultrasonic thickness gauge reads through paint; any local area more than ~15–20% thinner than nominal should be treated with extra caution. Press lightly with your thumb: if the panel deflects more than adjacent areas, corrosion has likely compromised stiffness.

Complement those with context: water paths (window seals, drain holes), salt exposure, and previous bodywork. If rust appears around a chip away from seams, odds are better it’s surface or shallow pitting. If it tracks along a pinch weld or seam sealer, expect scale from the inside. Combine the tests, not just one, to avoid false confidence.

Abrasives and surface prep for rust repair

Once you’ve classified the corrosion, match abrasives to the job. As a materials engineer, I test discs by cut rate (grams per minute), heat rise (infrared), and surface profile (Ra). Different grains and backings behave differently on oxide versus steel.

Aluminum oxide (A/O): A friable, workhorse grain that micro-fractures to expose new edges. It excels at surface rust removal where you want controlled cut without gouging. Use 120–180 grit on a DA sander at moderate RPM with dust extraction. Produces a consistent 60–90 µin profile suitable for epoxy primer.

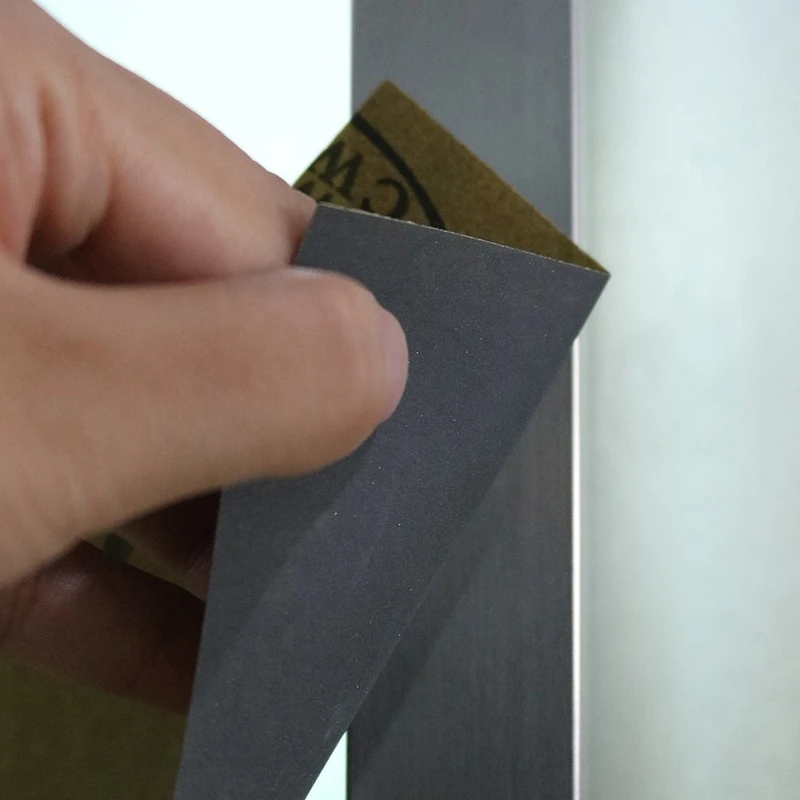

Silicon carbide (SiC): Sharper but more brittle than A/O. Effective on hard oxides and at feathering edges. Great for wet sanding to limit dust and heat. Use 180–320 grit for fine cleanup after heavier removal.

Zirconia alumina (Z/A): Tougher, self-sharpening under pressure. Ideal for scale rust. A 60–80 grit zirconia flap disc removes layers quickly with less glazing. Control heat and pressure—keep the disc flat to avoid creating low spots.

Ceramic alumina: High-performance for heavy stock removal. If you must erase stubborn scale on thick sections (frames, hitches), 50–80 grit ceramic fiber discs on a 7-inch sander deliver maximum cut per watt. Overkill for thin body panels unless handled with extreme care.

Nonwoven and wire tools: Coarse nonwoven “rust stripper” wheels remove coatings without as much base metal loss. Twisted wire cup brushes are aggressive on scale edges but can smear rust; use to expose, then switch to bonded abrasives.

Three to five actionable tips:

- Keep the work cool: Aim for less than 65°C (150°F) surface temperature. Heat accelerates flash rust and warps thin panels. Use short passes and let the disc do the work.

- Chase rust past the visible edge: Sand or strip at least 10–20 mm beyond the last stain; undercutting is common with scale.

- Set a removal limit: If you lose more than ~0.2 mm on a 0.8 mm panel (25% thickness), stop and reassess. Consider cut-and-replace rather than thinning.

- After bare metal is clean and bright, immediately wipe with solvent and apply an epoxy primer or a zinc-rich primer; avoid self-etch over areas with remaining converter.

According to a article

Chemical helpers have a place, but classification comes first. Rust converters (tannic or phosphoric acid based) stabilize shallow pitting after mechanical removal, forming iron tannate or phosphate layers. They’re not a substitute for grinding off scale. For perforations or deep pits, converters can only act as a stopgap beneath a reinforced repair—think fiberglass/epoxy on non-structural skins—until proper metal replacement.

Repair choices, costs, and risk

Once you know what you’re dealing with, decisions get clearer. For surface rust with intact thickness: mechanical removal to bright metal, degrease, epoxy primer, seam sealer where appropriate, and topcoat. Consumables cost is low: $20–$60 in discs and paper, $30–$60 in primer, plus small tools. Time: 1–3 hours for a palm-sized area.

Scale rust bridges into the grey zone. After you remove all loose oxide, evaluate pit depth. If pits are shallow (<0.3 mm) and the panel still rings, you can fill the profile with a metal-filled epoxy or body filler over epoxy primer, then seal. Expect $60–$150 in materials and 3–6 hours including cure times. However, if pits approach the thickness of the panel or run near seams, you’re postponing the inevitable. Plan for cut-and-weld.

Perforation demands metal replacement in structural areas (sills, frames, suspension mounts). Non-structural skins (outer fenders) can be patched, but only if the surrounding steel is unquestionably sound. Your risk assessment hinges on load paths: if the rust intersects a load-carrying member, the safe choice is to replace. Professional rates vary, but a fist-sized perforation with a simple patch often lands in the $300–$600 range for cutting, fabrication, and welding, plus paint. Complex inner-outer structures can exceed $1,500.

About coatings: Epoxy primers offer excellent barrier properties and adhesion to properly prepared metal. Self-etch primers bite into bare steel but can conflict with some fillers and aren’t a bandage for residual rust. Moisture-cured urethane rust paints are forgiving in imperfect prep but work best on cleaned, tightly adherent rust (no loose scale) and as part of a sealing system with topcoat and cavity wax.

A practical rule set:

- If tapping dulls and thickness loss exceeds ~20% in a critical area, do not rely on filler—replace metal.

- If the rust originates inside a seam or box section, open it up. Surface fixes outside won’t stop moisture feeding from behind.

- Budget not only the visible spot but the “rust shadow”—often 2–3x larger after media removal.

Field examples and an inspection routine

Let’s walk a realistic inspection on a 10–15-year-old daily driver in a rust belt climate.

Start with the roof rails and windshield frame. Look for paint nicks and faint browning at the edges. Wipe clean, then use your magnifier. Chips with shallow orange are typically surface rust—sand, prime, seal. But any bubbling at the windshield corners, especially coupled with a dull tap sound, suggests scale originating from the pinch weld. Probe the seam sealer; if it lifts easily and reveals black rust, plan for deeper work.

Move to wheel arches and quarter panels. Inside the lip, feel for roughness; salted spray collects here. If you find blisters, scrape the inner lip—if flakes shed and continue under paint, it’s scale. If the inner lip is intact and only the outer skin has peppered spots, you’re in surface rust territory. Clean, abrade, and seal the edge with epoxy and flexible seam sealer to block future intrusion.

Check rocker panels and jacking points. This is where decision-making turns consequential. Use the tap test along the pinch weld. If the weld seam shows continuous dullness or your pick penetrates drain holes with little effort, you’re near perforation from inside. Non-invasive “repairs” here give a false sense of security; the rocker ties into the car’s stiffness. Plan on cut-and-replace sections.

Underneath, inspect frame rails or subframes, especially near suspension mounting points. Light surface rust presents as uniform orange-brown that wipes to dark streaks and sands bright quickly. Scale shows dark patches and swelling around bolt heads. If a hammer knocks off chunks, expect pitting; measure thickness if possible. Hitches and receivers often show accelerated corrosion; while they’re bolt-on and non-structural to the chassis, their load rating depends on wall thickness. If you see perforation or extensive scaling, replacement is safer than restoration.

Finish with doors and tailgate seams. Open drains should be clear. Rust streaking from drain holes tells a story of moisture trapped inside—an early sign that can still be reversed if you act: flush, dry, and flood with cavity wax after treating any surface rust. Build a notes list: location, classification (surface/scale/perf), action (sand/prime, convert/fill, cut/weld), and parts needed. This turns inspection into a repeatable routine rather than a guessing game.

How to Repair — Video Guide

There’s a helpful demonstration of non-welding techniques in “How to Repair Rust Holes on Your Car Without Welding,” showing a straightforward approach for cleaning, reinforcing, and finishing corroded areas. The presenter walks through aggressive rust removal, panel prep, and building strength with fiberglass and fillers—useful for non-structural skins where metal replacement isn’t feasible immediately.

Video source: How to Repair Rust Holes on Your Car Without Welding

1500 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (50-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Professional ultra-fine grit for satin or semi-gloss finishing. Removes micro-scratches from clear coats and paint touch-ups. Produces flawless textures and consistent results before final polishing. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: How do I tell surface rust from scale in five minutes?

A: Clean the area, inspect with a bright light and magnifier, then do a pick-and-scrape and tap test. Surface rust powders off and leaves bright metal with a crisp ring; scale lifts in flakes, reveals pitting, and dulls the sound as you tap.

Q: Can rust converters fix scale or perforation?

A: Converters can stabilize shallow residual rust in pits after mechanical removal, but they don’t rebuild thickness or penetrate layered scale deeply. For perforation, metal replacement or reinforced patching (non-structural only) is required.

Q: What grit and abrasive should I use for each stage?

A: For surface rust, 120–180 grit aluminum oxide on a DA sander is safe and effective. For scale, 60–80 grit zirconia flap discs or ceramic fiber discs (on thicker parts) remove layers efficiently. Follow with 180–320 grit (SiC or A/O) to refine before primer.

Q: When is filler acceptable in rust repair?

A: After removing rust to clean metal and applying an epoxy primer, filler can level shallow pitting in non-structural panels. Avoid filler over active rust or in areas with significant thickness loss, seams, or any perforation—those require metal repair.

Q: How do I prevent rust from returning after repair?

A: Control moisture ingress and protect the surface: use epoxy primer, seam sealer at joints, quality topcoat, and flood closed sections with cavity wax. Keep drains clear and wash winter salt promptly. Regular inspections catch early surface rust before it escalates.