How to Track and Tension Sanding Belts Right

I still remember the first time a belt sander reminded me who’s boss. I was flattening a salvaged maple countertop in a cold garage, heater humming, coffee cooling. The sander sounded healthy at idle, but as soon as I leaned into it, the belt crept right, kissed the guard, and started singing. Within thirty seconds, grains glazed over on one edge, dust plumed unevenly, and the finish was streaky. I backed off, re-centered, nudged the tracking knob a hair, and tried again. Same result—only now the seam thumped every revolution. The culprit wasn’t just a “bad belt.” It was a bad setup: improper tension and unstable tracking.

That day sent me down a rabbit hole testing how sanding belts behave under real loads. I instrumented my benchtop 4x36 and a 1x30 with a handheld tachometer to capture belt speed under load, an IR thermometer to track seam heat, and a simple digital luggage scale to quantify tensioning force. I marked the belt edge with a Sharpie to quantify drift per minute. What I learned is simple but powerful: belts don’t wander randomly. They react to roller geometry, belt construction, splice accuracy, backing stiffness, and—most of all—tension.

Get tension wrong and everything downstream degrades: tracking goes unstable, seams overheat, bearings suffer, dust extraction falls off, and finish quality turns inconsistent. Track poorly and the belt edge loads up, grit fractures prematurely, and you waste abrasives. With the right numbers and a repeatable workflow, though, the same machines that frustrate will cut flat and predictable. This article lays out the mechanics, the measurements, and the step-by-step process I use to track and tension sanding belts so they run straight, cut cool, and last long.

Quick Summary: Stable tracking and correct tension come from understanding roller geometry, belt construction, and measurable force targets—then following a repeatable calibration and diagnostic routine.

The mechanics behind belt tracking

Tracking is mostly physics and a bit of manufacturing reality. A belt will climb toward the high side of whatever surface it’s riding on. That’s why many drive or idler rollers have a crown—a very slight convex shape—to center the belt. If the crown is too subtle, contamination flattens it, or the belt backing is stiff and curved from storage, the centering force weakens and the belt hunts. Conversely, a pronounced crown can overcorrect, making tiny tracking knob inputs swing the belt from side to side.

Two construction details influence this balance: splice geometry and backing stiffness. Most belts are either lap-spliced (one end overlaps the other with adhesive) or butt-spliced with a thin film on the backside. Lap splices create an asymmetry that can induce a periodic lateral force—felt as a rhythmic “tick” and observed as a slow drift on light-tension setups. Butt splices are more neutral but rely on film strength; poorly made films can print through and bump against platen edges.

Backing matters, too. J-weight (flexible) backings drape over crowns and conform, requiring less tension to stabilize; X- or Y-weight backings are stiffer, resist conforming, and may need higher tension to overcome their inherent “memory.” Humidity is a silent player: cotton backings can absorb moisture, slightly growing and curling, which pushes the belt to one side. Polyester backings are more moisture-stable but can be springier, transmitting more vibration if tension is low.

Heat and friction round out the picture. Lateral forces increase as the cutting load rises and the seam warms; warm adhesive becomes more compliant, changing how the splice crosses the rollers. If the tracking system (typically a pivoting idler with a fine knob) has play or stiction, your micro-adjustments won’t actually move until torque builds—then they overshoot. In testing, I’ve seen “deadband” behaviors of ±0.1–0.2 turns on some hobby machines. Fixing that is rarely about replacing the knob; it’s about cleaning the pivot, checking bushings, and ensuring a true, smooth idler.

Tensioning by numbers, not guesswork

Most guidance says “tight enough that the belt doesn’t slip.” That’s vague, and it leads to over-tensioning. Over-tensioning masks tracking problems briefly, at the cost of seam life and bearings. Under-tensioning gives instant feedback—slip and drift—but wastes time. The practical fix is to quantify tension on your specific machine and belt width.

On small spring-arm sanders (1x30, 4x36, 6x48), use a digital luggage scale to measure the force you apply to the tension arm or directly to the belt mid-span. Two quick methods work:

- Arm-pull method: Hook the scale to the tension lever or spring anchor and measure the force at the engaged position. Note the force that corresponds to the manufacturer’s tension mark, then test ranges above/below while monitoring tracking stability and seam temperature.

- Mid-span deflection method: With the machine unplugged, hook the scale onto the belt at the longest exposed span and pull 6 mm (1/4 in) of lateral deflection. Record the pounds of force required. Repeat at several positions to average out splice effects.

Targets that yielded stable tracking in my tests:

- 1x30: 2–4 lbf for J-weight belts; 3–5 lbf for X-weight

- 4x36: 5–7 lbf (J) and 6–9 lbf (X/Y)

- 6x48: 8–12 lbf (X/Y)

These aren’t absolutes—they’re starting points that minimize slip while avoiding seam overheat. To validate tension, I log three metrics over a one-minute sanding pass on hardwood:

- Belt speed drop under load (tachometer): aim for <8% drop.

- Seam temperature rise (IR): keep peak <70°C (158°F) on the seam area.

- Lateral drift (Sharpie on belt edge): less than 1 mm/min without operator correction.

If you can hold those targets, you’re in the sweet spot. Too low a tension shows as speed dips >10% and audible squeal on startup or during heavy cuts. Too high a tension shows as a rising seam temperature even at light load and subtle bearing hum. A safety note: never exceed the machine’s rated tension or spring pre-load. If hitting the targets seems to require excessive force, you likely have roller alignment or crown issues that tension alone can’t fix.

Diagnosing drift and chatter in sanding belts

When belts wander or thump, systematic diagnosis beats random knob-turning. Here’s the routine I use.

Start clean. Remove the belt, vacuum dust from the platen, guides, and rollers. Wipe rollers with mineral spirits to remove pitch. Spin them by hand; feel for bumps, listen for bearing roughness. Lay a straightedge across the idler roller to check for crown; you should see 0.2–0.5 mm of rise in the center on small benchtop machines. No crown or flat spots? That’s a red flag.

Inspect the belt. Identify the splice type and direction arrow. Lap splices should enter the work with the overlap trailing (so the overlap doesn’t catch the workpiece). Feel the seam; if it’s proud, know that it will pulse. For cloth backings, flex the belt to see if it springs back evenly; a set curl to one side will bias tracking until the belt warms and relaxes. Store belts in a large diameter loop to minimize memory.

Mount and set baseline. Center the belt on the rollers by hand. Set tension to the low end of the target range and start the machine. Nudge the tracking knob until the belt stabilizes near center with no operator input. Make small changes—wait 5–10 seconds after each 1/16 turn to observe. If the belt oscillates across the full width, you’re over-correcting or the pivot is sticking; stop and lubricate the tracking pivot bushings lightly with a dry PTFE spray, then try again.

Cut test. With a stable idle, make a light pass on scrap and watch the edge witness mark. If drift appears only under load, check platen flatness and pressure distribution. Uneven platen contact or worn graphite slip cloth will push the belt sideways under pressure. If drift persists, swap belts. Consistent drift with multiple belts points to machine geometry; drift with a single belt implies belt construction (splice misalignment or backing curl). According to a article.

Chatter is usually splice-related or tension-related. A pronounced thump that repeats once per revolution suggests seam thickness or adhesive lump. Slight rhythmic streaking can come from grit shelling or joint shear—but if it diminishes as tension increases slightly, you were under-tensioned. If heat and noise rise sharply with higher tension, you’ve gone too far or the seam is defective. Replace that belt rather than chasing perfect tracking with bad material.

Calibration workflow for consistent results

Consistency comes from doing the same steps every belt change. Here’s the workflow I follow for new belts or after maintenance.

Verify machine geometry

- Check that the drive and idler shafts are parallel using a straightedge and feeler gauges. Parallel misalignment as small as 0.2 mm across the roller face can induce a steady lateral bias.

- Confirm crown condition. If the crown is contaminated, wrap a sacrificial belt and lightly dress the roller with a fine abrasive stick while rotating by hand. Do not remove crown—just clean it.

Baseline tension and tracking

- Set tension to the low end of your known range (use your luggage scale values).

- Start the machine and center-track at idle with micro-adjustments, allowing each change to settle.

Load validation

- Make a uniform pass on hardwood with moderate pressure. Record belt speed drop, seam temperature, and lateral drift. Increase tension by 0.5–1 lbf if drift appears only under load, then re-test.

- If drift direction flips when you change pressure points (e.g., firm pressure near the infeed vs. outfeed), check platen and table alignment.

Document a “machine card”

- Record the tension force (from the luggage scale), tracking knob position (e.g., zeroed mark and ± turns), and ambient humidity/temperature.

- Keep separate entries for belt types (J, X, Y backings) and grits. Different constructions settle differently as heat builds; noting this saves time later.

Proactive seam protection

- Warm up a cold shop belt for 30–60 seconds at idle before heavy cutting; adhesive and backing stabilize with temperature, reducing early drift.

- Break in coarse belts with a few light passes to knock down high grains—this reduces seam shock without dulling the belt.

Actionable tips you can apply today:

- Use a digital luggage scale to quantify your tension. Record the force at the arm when achieving stable, cool runs; repeat that target each belt change.

- Mark the tracking knob “zero” and log the final stable position in quarter-turns for each belt type.

- Replace worn graphite platen pads; a fresh, low-friction surface stabilizes tracking under pressure.

- Store belts in a large coil (18–24 in diameter) in sealed bags; avoid humidity swings that warp cotton backings.

- Clean roller crowns with a resin remover; tiny pitch patches act like micro-crowns and push belts sideways.

Materials, joints, and belt quality

All sanding belts aren’t equal, and quality differences show up fast in tracking and tension sensitivity. Start with abrasive grain. Aluminum oxide (AO) is tough and friable enough for general woodworking; it’s typically paired with J or X cotton backings. Zirconia alumina is tougher and self-sharpens under pressure; many come on Y-weight polyester or heavy X cotton for longevity. Ceramic alumina (and ceramic blends) cut coolest at high pressure and speed, but they demand stable tracking and higher tension to keep grains engaged.

Backings drive stiffness and stretch. J-weight cloths are flexible, conforming to crowns and curves—friendly for narrow belts and slight roller imperfections. X-weight is a workhorse for 4x36 and 6x48, balancing stability with some compliance. Y-weight polyester backings are moisture-resistant and durable, but their springiness transmits wobble if tension is too low. Polyester also shrugs off humidity swings, so storing these belts is easier.

Splice construction is the hidden variable. Lap splices have a step that can thump; the best are skived thin and precisely aligned. Butt splices with a film on the backside run smoother, but the film quality matters. Cheaper films soften under heat and can delaminate; that shows up as sudden tracking change mid-cut. Check for “bi-directional” arrows—if the manufacturer advises a direction, honor it; the splice geometry is optimized for that orientation across the platen.

Adhesives and resin systems affect heat performance. Closed-coat belts (more grain coverage) cut aggressively but generate more heat; open-coat belts shed dust better and run cooler in resinous woods. Antistatic treatments reduce dust cling, improving extraction and keeping the belt face cleaner; a cleaner belt tracks more consistently because load distribution stays even. Finally, avoid aging belts to the point the splice adhesive dries out. If a belt feels brittle or the splice creaks when flexed, retire it. A popped seam isn’t just wasteful; it can damage guards and wrists.

In tests across a dozen brands, I’ve seen cheap belts run acceptably if you hit the right tension and don’t overload them. But their window of stable tracking is narrower, and they heat the seam faster. Premium belts with better splice control and consistent backing thickness give you a wider stable range. If you value time and consistency, that matters more than headline grit specs.

I Bought These — Video Guide

A recent video from a deck builder compares ultra-cheap, around eight-dollar sanding belts with pricier options during real decking work. The host runs multiple belts back-to-back, noting how quickly they glaze, whether seams stay cool, and how stable they track under typical pressure. It’s a practical look at how construction quality shows up minute-by-minute.

Video source: I Bought These $8 Sanding Belts And... Ohh Boy || Dr Decks

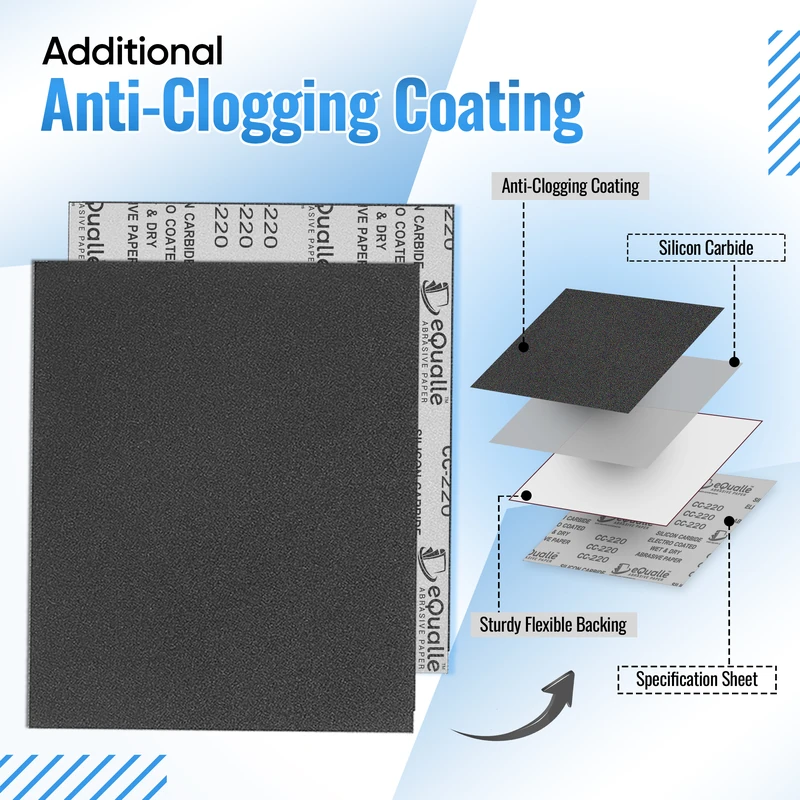

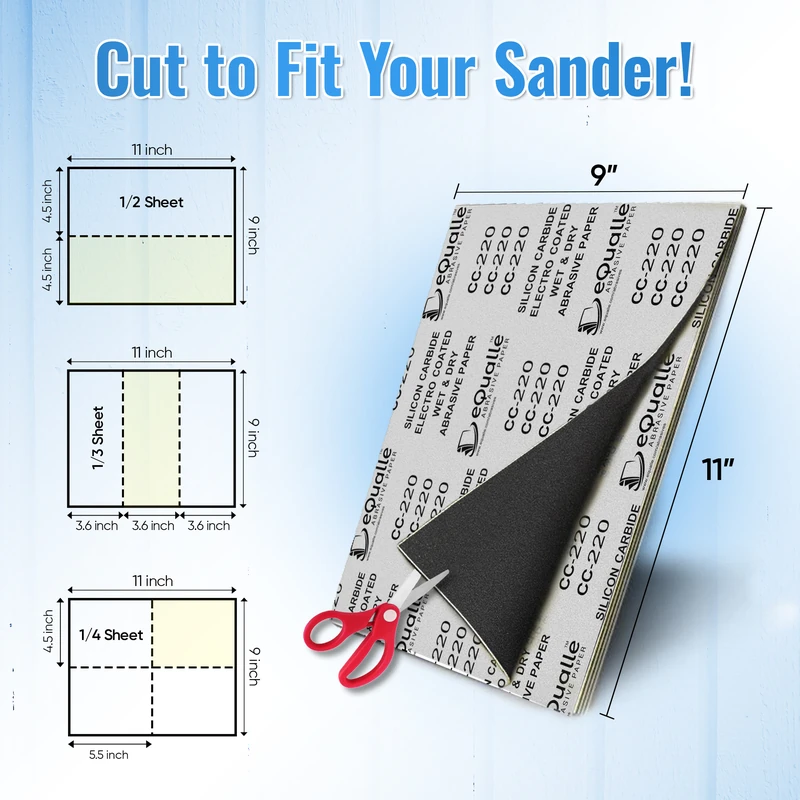

100 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (100-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — General-purpose coarse sandpaper for smoothing rough surfaces and removing old coatings. Works well on wood, metal, and resin projects. Designed for wet or dry sanding between aggressive 80 grit and finer 150 grit stages. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What’s a good starting tension for a 4x36 benchtop sander?

A: Using the mid-span deflection method, aim for 5–7 lbf with J-weight belts and 6–9 lbf with X/Y backings. Validate by keeping belt speed drop under 8%, seam temperature under 70°C, and drift under 1 mm/min during a one-minute pass.

Q: Why do my sanding belts walk only when I press harder?

A: Load shifts change contact pressure across the platen, amplifying minor crown or platen unevenness. Under tension, the belt doesn’t resist that lateral force. Verify platen flatness, replace worn graphite pads, and increase tension by about 1 lbf, then re-center track.

Q: How do I know if I’ve over-tensioned the belt?

A: Signs include rising seam temperature at light load, bearing hum, and increased vibration. If your tach shows minimal speed drop but the seam hits 70–80°C quickly, back off tension by 1–2 lbf and re-test.

Q: Do different abrasive grains affect tracking stability?

A: Indirectly. Ceramic and zirconia belts typically use stiffer backings and run best at slightly higher tension. AO on J-weight backing conforms more easily to the crown and may track fine at lower tension, but it’s more sensitive to humidity.

Q: How should I store belts to avoid tracking problems later?

A: Coil belts loosely (18–24 in diameter), keep them in sealed bags, and store at stable humidity. This prevents backing curl and splice stress that can bias tracking when first installed. Warming a cold belt at idle for 30–60 seconds helps it settle before cutting.