Grit Steps That Unlock Beautiful Concrete Polishing

The café opens just before sunrise, the first light catching on cups and chrome as someone flips the sign to “Open.” Footsteps echo across the floor—once dull, scuffed, and interrupted by patchy coatings. A few weeks ago, the owner debated a full remodel. Instead, she chose a different path: refining what was already there. With a plan centered on careful grit steps, the team ground, honed, and finally achieved a reflective finish through concrete polishing. Now the floor turns light into soft ribbons. It feels new without losing its character; the aggregate tells a story, the surface is smooth, and maintenance is suddenly predictable. People pause when they walk in. They notice the room before they notice the menu.

That transformation isn’t a magic trick. It’s craftsmanship and sequence. The clarity you see in a polished surface is created by the choices you make with abrasives: how coarse you begin, how thoroughly you erase the previous scratch pattern, when you densify, and how far up the ladder you climb. Each decision leaves a fingerprint. The result can be a matte satin that absorbs daylight or a mirror-like sheen that turns concrete into a design feature.

If you’re new to the process, this guide will unpack the grit steps for honing and polishing—what they do, when to use them, and how to avoid common pitfalls. If you’re experienced, consider it a tune-up: a chance to tighten your sequence, sharpen your inspections, and select tools that deliver consistent, repeatable results on real-world slabs. Either way, the fundamentals don’t change: a disciplined sequence, matched to the slab in front of you, is what makes great floors look effortless.

Quick Summary: The right grit progression—verified at each step—turns raw concrete into a durable, low-maintenance finish with reliable clarity and shine.

From grind to gloss: the big-picture path

Concrete finishing is a process of refinement, not just removal. The path from raw slab to high-gloss finish moves through three stages: grinding, honing, and polishing. Each stage uses different grit ranges and bonding types to control both the depth and shape of scratches, which determines how light reflects off the surface.

- Grinding establishes the plane and exposure. Metal-bond diamonds in coarse grits (often 16–40) remove high spots, coatings, and profiling marks; intermediate metals (60–80) and finer metals (100–150/180) flatten and begin closing the surface. Think of grinding as setting the canvas—flatness, exposure level, and initial scratch uniformity.

- Honing transitions from metal removal to surface refinement. Resin or transitional hybrid pads between roughly 50 and 400 grit reduce scratch depth, even out the surface, and start producing a soft, diffuse sheen. A thorough hone eradicates the last remnants of metal scratches and makes later polishing efficient.

- Polishing increases clarity and reflectivity. Resin pads at 400–800–1500–3000 (and sometimes higher) tighten the surface so that light reflects cleanly. This is where you see “depth,” not just shine.

Two levers define your result: the chosen sequence and the quality of scratch removal between steps. Skipping verification leads to haze or “ghost scratches” that show up at the worst time—right when you expect the final gloss. Before moving up, confirm that the current grit has completely erased the previous one. This discipline moves you from “shiny but cloudy” to “glossy and crisp.”

Densifiers and guards support the sequence, not replace it. Densifier is typically applied during honing once the slab is receptive; a topical guard may fine-tune gloss and stain resistance but should never be used to hide incomplete refinement. In short: set the plane, refine the surface, then elevate the reflectivity—with a grit ladder that makes sense for your space, timeline, and performance goals.

Choosing grit sequences for concrete polishing

While no two slabs are identical, proven grit ladders remove guesswork. The key is to choose a starting grit based on slab condition and to climb in manageable increments that fully remove the previous scratch pattern before moving on. Below are common sequences for different scenarios.

- Heavy removal and medium aggregate exposure:

- Metals: 30/40 → 60/80 → 120/150

- Transition: 50/70 hybrid

- Resins (honing): 100 → 200 → 400

- Resins (polishing): 800 → 1500 → 3000

- Light removal or cream finish:

- Metals: 60/80 → 120/150 (or begin with a sharp 80 if flat)

- Transition: 50/70 hybrid as needed

- Resins (honing): 100 → 200 → 400

- Resins (polishing): 800 → 1500

- Remodel with tight timeline (moderate gloss target):

- Metals: 60/80 → 120/150

- Resins (honing): 100 → 200 → 400

- Resins (polishing): 800

- Finish with guard for easier maintenance

Honing typically concludes at 200 or 400, depending on your definition and desired sheen. Many contractors consider 400 the first true polishing step because you begin to see more specular reflection; others mark 200 as the end of honing. What matters is consistent criteria on your projects.

H3: Typical grit ladder by goal

- Satin matte, high clarity: up to 400 or 800, guard optional

- High-gloss traffic areas: to 1500 or 3000, densify mid-hone

- Maximum distinctness of image (DOI): to 3000, burnish, tight maintenance

According to a article. It reinforces a core truth: once you reach 200–400, you’re not removing much material—you’re perfecting scratches and closing pores. That mental shift helps you slow down, verify, and avoid chasing gloss with too-fast grit jumps. Keep grits close enough that each one truly erases the previous: doubling or less is a safe rule (e.g., 100 → 200 → 400 → 800).

Reading the slab: variables that change the plan

Good contractors don’t choose grits in a vacuum. They read the slab and adapt. Several variables influence your starting grit, increments, and support chemistry.

- Hardness: Soft concrete (low psi mix, high sand, young slabs) can “micro-fracture” under metals and load up resins. Hard slabs resist cutting, demanding sharper tools and more dwell time. A simple scratch test or Mohs kit helps define the approach. Softer slabs may favor slightly higher metal grits (e.g., start at 60/80) to avoid tearing cream and creating deep scratches that are hard to remove later.

- Aggregate exposure: Desired exposure dictates how deep you cut. Cream finishes require minimal metal passes and perfect flatness; salt-and-pepper needs controlled, uniform grinding; larger aggregate exposure means coarser starting grits and more metal passes. Remember: exposure is permanent—commit before you start.

- Surface history: Coatings, mastics, and patchwork require tailored removal steps, edge tooling, and often a test area to gauge productivity. Transitional pads are your friend when metal scratches resist resins, especially around repairs or soft/hard variations.

- Moisture and porosity: Highly porous surfaces benefit from a mid-hone densifier application (often after 100 or 200 resins) to consolidate paste, improve scratch response, and tighten pore structure. On very tight, hard surfaces, densify later (after 200/400) so it can penetrate effectively.

- Edges and detail: Edges and columns can telegraph as dull bands if their grit ladder doesn’t match the field. Plan edge tooling with the same grit sequence, and aim for blended scratch patterns rather than “close enough.”

Document what the slab tells you in the first 200 square feet. Adjust head pressure, tool choice, and grit increments based on dust, scratch morphology, and how quickly each step erases the last. In other words: let the slab write the spec, and let your sequence respond.

Execution: passes, dust control, and inspection

Technique turns a solid grit plan into a standout floor. When execution is disciplined, you’ll see fewer surprises in the final gloss.

- Overlap and speed: Maintain consistent, 30–50% overlap with steady machine speed. Too fast leaves “racing stripes”—visible at higher grits as alternating dull and bright bands. If you can’t tell whether a pass erased the previous one, slow down and add overlap.

- Head pressure and tooling: Match pressure to grit and slab. Excess pressure can create deep, noisy scratches at low grits and cause resin pads to hydroplane or burn at higher grits. Let the diamonds cut; don’t force them. Keep discs sharp—dress metals as needed and swap resins before they glaze.

- Dry vs. wet: Dry grinding with effective dust extraction speeds inspection and keeps the work area clean. Wet honing or polishing can reduce heat and extend resin life but complicates visual checks and cleanup. If you go wet, rinse thoroughly and avoid slurry trails that re-deposit fines, which dull the finish.

- Inspection cadence: After each grit, stop and check the surface under varied light (raking light is your best friend). Look for parallel scratch lines from the previous grit, resin halos, or “picture framing” around aggregate. If you see ghosts, you’re not done—don’t climb the ladder yet.

- Clean between steps: Vacuum meticulously. Fine dust left behind acts like rogue abrasive, creating micro-scratches at the next grit. Wipe checks with a white microfiber towel—if you see gray, keep cleaning.

Densifier timing matters. On absorbent slabs, apply after 100 or 200 resins. On tight, hard surfaces, shift to 200 or 400. Work it in evenly, allow proper reaction time, then remove excess to avoid brittle residue that can blur clarity. Finally, consider a light burnish at the end (especially after 1500–3000) to pop the finish—just make sure the underlying scratch work is complete, or you’ll only burnish in the haze.

Pro tips for consistent clarity

Small habits compound into clean outcomes. These field-tested tips help you preserve clarity and reduce callbacks.

- Map the floor in zones: Divide the job into manageable sections (e.g., 400–600 sq ft) and complete the full grit ladder in each before moving on. This prevents inconsistent dwell times and tool life variations that cause patchy gloss.

- Use “erase tests” at every jump: On each new grit, run a short pass and inspect if the new scratch fully erases the last. If not, adjust pressure, speed, or grit—not later when haze is locked in.

- Break edges early: After your first metal pass, edge to the same grit before climbing. Repeat at each stage. The cost of returning to fix a dull perimeter is far higher than staying synced as you go.

- Calibrate with a gloss or DOI meter: Quick readings at 400, 800, and final step help confirm your process is trending in the right direction. Use them as checks, not goals—visual inspection still rules.

- Keep a “rescue” pad handy: A transitional hybrid around 50/70 or a sharp 100 resin can clean up stubborn metal signatures. If you hit 200/400 and see faint lines, don’t climb; drop one step, fix them, then proceed.

H3: When to stop climbing

- Stop at 400–800 for satin clarity and slip-conscious spaces.

- Go to 1500 for high-gloss in retail entries and showrooms.

- Add 3000 and burnish where maximum DOI is the design intent.

- If maintenance will be minimal, favor a slightly lower final grit with a quality guard—more forgiving in the long run.

Precision isn’t about doing more steps; it’s about doing the right steps, thoroughly. Finish each stage cleanly, and the next one becomes easier, faster, and more predictable.

Polishing with Micro — Video Guide

A helpful demonstration shows how a complete abrasive progression builds shine: using micro-mesh pads in nine increasing grits to move from dull to glossy. While the example isn’t concrete-specific, the principle is identical—each grit removes the previous scratch pattern and tightens the surface until it reflects light cleanly.

Video source: Polishing with Micro Mesh Pads

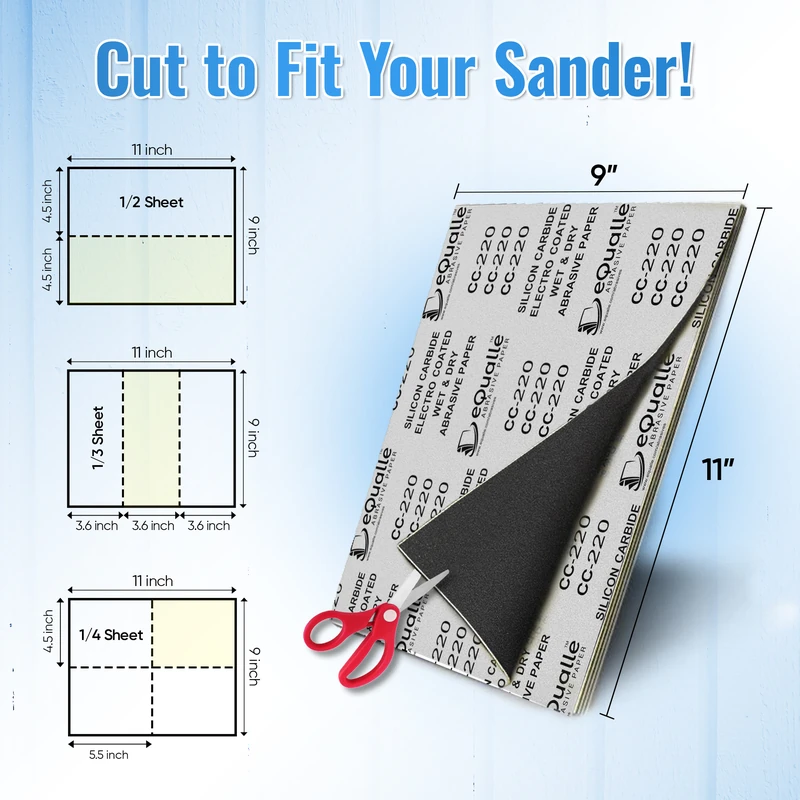

2000 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (100-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Super-fine grit for restoring deep gloss on automotive paint, resin, or metal. Removes micro-defects and surface haze. Ideal for precision polishing prior to waxing or compounding. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What’s the difference between honing and polishing on concrete?

A: Honing (roughly 100–400 grits) refines the surface, removes metal scratches, and builds a matte to low-sheen finish. Polishing (often 400–3000) increases clarity and reflectivity, tightening the surface so it reflects light sharply. Densifier is often applied during honing to support both stages.

Q: When should I apply densifier in the grit sequence?

A: On porous or softer slabs, apply after 100 or 200 resins to consolidate the paste and improve scratch response. On dense, hard slabs, shift to after 200 or 400 so it can penetrate. Always remove excess to prevent residue that clouds clarity.

Q: Can I skip grits to save time?

A: Skipping usually costs more time later. Each grit must fully erase the previous scratch pattern. If you need efficiency, reduce the number of passes at each grit—but keep logical jumps (e.g., 100→200→400→800). Verify with raking light before moving up.

Q: How far should I polish—800, 1500, or 3000?

A: Match the final grit to appearance and maintenance. 400–800 suits satin finishes and higher-traction needs. 1500 is a high-gloss sweet spot for many retail spaces. 3000 adds maximum DOI and depth but demands consistent maintenance to keep the look.

Q: Dry or wet polishing—what’s better?

A: Dry cutting with strong dust extraction improves inspection and speed; wet steps can extend pad life and reduce heat. Many teams grind dry, hone wet for certain slabs, and finish dry. Choose based on slab behavior, tools, and your dust control capability.