Boat Sanding: Wet Techniques to Control Marine Dust

There’s a particular quiet to the yard before sunrise. The halyards ping, the coffee steams in a chipped thermos, and the hull you’ve been avoiding stands there like a promise you can’t put off. I’ve been on both sides of that moment—rushing, dusty, and regretting shortcuts later—and the method that changed the game for me was wet boat sanding. Not because it’s pretty, but because it’s efficient, safer for your lungs, and easier to keep the neighbors and the yard manager happy. You control the mess. You protect the water you love. And you end the day with a hull that’s flatter, cooler, and ready to bond.

If you’ve ever sanded antifouling dry, you know the aftermath: paint dust on everything, the sickly chemical tang in the air, and the nagging worry that you’re spreading toxins. Wet sanding flips that script. The water captures the particles before they can fly, keeps abrasives from loading, and absorbs heat so you don’t smear paint or burn gelcoat. It’s the same mindset I bring to the shop: slow is smooth, smooth is fast. Prep right, move steadily, and every pass counts.

Picture the workflow. Bunded tarps catch slurry. A bucket with a dash of surfactant keeps the paper cutting. Your sander hums—not screams—while you guide it with two hands, crossing passes like mowing a lawn. The rinse water doesn’t run away; it’s contained, vacuumed, and disposed of correctly. At the end, you don’t look like you fought a chalk storm. You look like someone who planned the work and worked the plan. That’s the heart of good craftsmanship—taking control of the process so the results take care of themselves.

I’m going to walk you through the exact setup, the grits that work, the pressure that won’t gouge, and the cleanup that keeps you compliant. Whether you’re a first-time DIYer or a pro with a packed spring calendar, wet sanding is the clean, consistent path to a better hull.

Quick Summary: Wet sanding captures dust at the source, keeps surfaces cool, and delivers flatter, cleaner results—if you plan containment, use the right grits, and manage slurry.

Plan the job, protect the water

Before you touch an abrasive, build the stage. Good wet sanding is 70% prep, 30% passes. Your goals: contain every droplet, keep the hull cool and wet, and give yourself a safe, repeatable workflow.

- Containment: Lay a heavy-duty ground tarp under the boat with a 3–4 inch bund (roll pool noodles or foam backer rod along the edges and tape them to create a dam). Tape plastic sheeting around the hull to create a skirt that overlaps the tarp by 6–8 inches. This way, rinse water and slurry run down, not out.

- Water source: Ideally, use a low-flow hose with a trigger nozzle. If you’re on a jetty or a yard without a hose, keep a 5-gallon bucket and a squeeze bottle. Add a small squirt of biodegradable soap to break surface tension; it prevents paper from clogging and helps the slurry settle.

- Power plan: If you’re running corded tools, use a GFCI and keep cords elevated. On remote docks, a quality inverter or a small generator with a long-duty eco mode is fine—just keep it clear of spray. Many pros go cordless for hull work; today’s brushless, variable-speed sanders have the torque.

- PPE: Yes, wet sanding slashes airborne dust, but antifouling and old coatings are still hazardous. Wear a P100 respirator, nitrile gloves, eye protection, and a disposable suit. Your future lungs will thank you.

- Yard rules: Walk the site manager through your plan so there are no surprises. Many yards require containment and waste capture; show them your bunded tarp, wet vac, and disposal plan.

Tips to lock in success:

- Work in shade or early morning to keep the substrate cool.

- Sand in 3–4 foot zones so slurry doesn’t dry on you.

- Always check the forecast—wind will move your tarp “walls” and spray. Reinforce with spring clamps.

Boat sanding the wet way: tools and setup

You don’t need a truckload of gear to do this right, but the right pieces make it efficient and repeatable.

- Sanders: A 5–6 inch random orbital sander (ROS) with variable speed is the workhorse. For bottom paint removal or leveling, add a geared dual-action (forced rotation) model. Keep speeds moderate; wet sanding relies on sharp grit and glide, not brute force.

- Interface pads and backing: Use a 5 mm foam interface pad for curved hulls and to prevent edge gouging. Stick with hook-and-loop discs—easier swaps when wet.

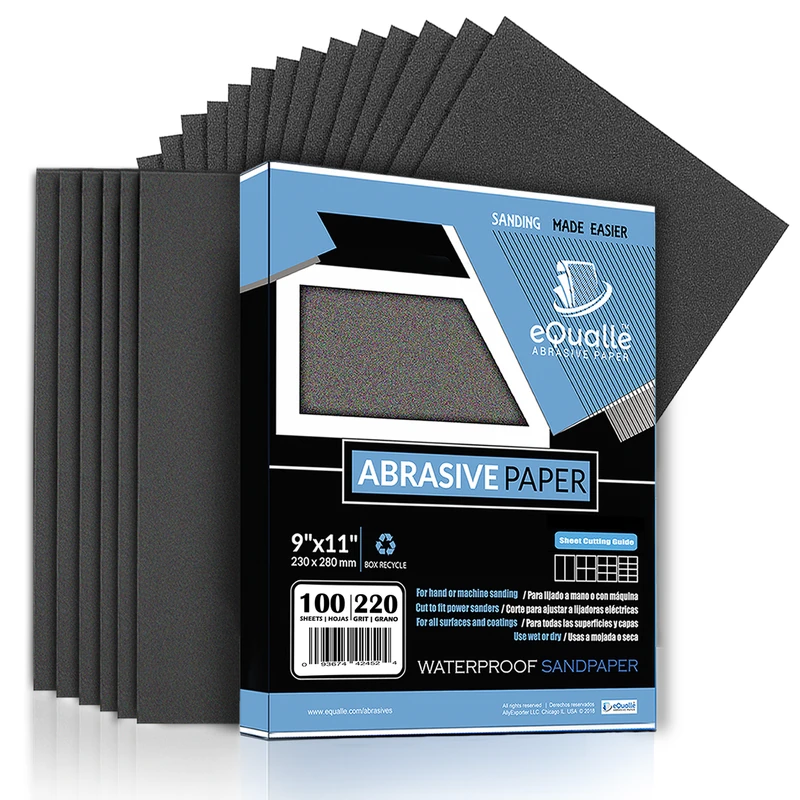

- Abrasives: Quality wet/dry discs matter. For antifouling scuffing between coats, 120–180 grit works. For heavier removal, 80–100 grit controlled passes. For gelcoat oxidation repair, move into 800–1500 grit ranges, finishing with 2000 if you’re polishing after.

- Water delivery: A trigger spray bottle keeps control at your fingertips. For continuous flow, a gentle hose mist is perfect. Don’t flood; aim for a thin film that carries slurry without making a skating rink underfoot.

- Buckets and additives: A 5-gallon pail with clean water gets refreshed often. Add one small drop of soap per gallon—enough to help, not enough to leave residue.

- Slurry capture: A wet/dry vac with a drywall bag and a water separator (a simple cyclone lid over a bucket works) lets you collect heavy slurry without wrecking the vac. Use absorbent socks at the base of the keel and under low spots to corral flows.

- Hand tools: A longboard or stiff, curved sanding block is insurance for problem areas near chines and around through-hulls. Power can’t reach everything.

Setup sequence I use:

- Lay and tape the tarp with a bund.

- Hang a skirt along the hull overlap.

- Stage your buckets, squeeze bottle, and vac on the “dry” side of the tarp so you don’t wade in your own mess.

- Mark 3–4 foot zones with painter’s tape; it keeps you honest about coverage and progress.

- Do a 12-inch test patch with your planned grit to verify removal rate and surface response.

Pro note: If your sander bogs when wet, reduce pressure, drop speed one notch, or step to a slightly coarser grit. Let the abrasive cut—your job is to guide.

Grit choices, passes, and pressure

The right grit and pass pattern are what separate a fast, flat job from a smeared, streaky one. Think in stages: cut, refine, and finish prep.

For antifouling paint:

- Scuffing between coats: 120–180 grit wet is plenty. You’re not trying to remove; you’re giving the new coat a tooth.

- Controlled removal: 80–100 grit with light pressure, crosshatching passes. If paint is thick or flaking, scrape the worst first, then sand; don’t try to “grind it all” with one grit.

For gelcoat oxidation:

- Start at 800–1000 grit wet for mild oxidation, 1200–1500 for maintenance. Move to 2000 before compound if you want a mirror finish with minimal heat.

Technique that works:

- Wet the panel until it shines but isn’t dripping.

- Hold the sander flat, two hands, and let it ride. Make 50% overlapping passes left-right, then up-down—like mowing a lawn.

- Keep pressure just enough to maintain contact. If the pad slows, you’re pressing too hard.

- Check the slurry color. Dark colored slurry means you’re cutting paint; if it turns translucent quickly, the grit is spent or you’re through the layer.

- Wipe, inspect with raking light, and pencil-mark high spots. Sand just until the marks fade; it’s a great control method for fairness.

Health check: According to a article, antifouling dust and residues are hazardous. Wet sanding reduces airborne risk, but you still need proper PPE and waste control.

Three guardrails to avoid damage:

- Edges and radiuses: Back off pressure and make shorter strokes; these areas thin first.

- Through-hulls and transducers: Hand-sand around them. Power tools can undercut bedding.

- Heat: If the panel feels warm to the touch, pause, mist, and move to the next zone.

When to step grits: If you’re pushing hard and going nowhere, step coarser. If the surface looks torn or “hairy,” step finer and lighten up. Always finish each zone before moving on—half-finished panels are where mistakes happen.

Manage slurry and stay compliant

You haven’t finished the job until the slurry is in a container and the hull is clean, de-waxed, and ready for what’s next. This is where pros earn their quiet yard exits.

Slurry capture and disposal:

- Keep the bund intact. As you work, use a floor squeegee to pull slurry to a collection corner. Vacuum it up periodically with your wet/dry vac hooked to a separator.

- Line your separator bucket with a contractor bag. Let solids settle overnight, decant the clear water back into your waste system, and tie off the bagged solids for hazardous disposal per local rules. Never pour into drains or soil.

- Wipe the hull with wet microfiber as you go; don’t let slurry dry on the surface. Dried fines are harder to remove and can contaminate coatings.

Surface prep for recoating:

- After sanding, wash the hull with clean water and a fresh microfiber to remove fines. Switch to new water as soon as it clouds.

- For topsides and gelcoat polish prep, follow with a dedicated surface prep: first a mild detergent rinse, then an appropriate solvent wipe (e.g., a dewaxer) with lint-free towels. Change towels often—cross-contamination creates adhesion failures.

- Check hull moisture if you’ve chased blisters or opened laminate. No coating goes over a wet substrate. Give it air and time.

Staying inside yard rules:

- Post a “wet work in progress” sign and keep your PPE on. Showing care goes a long way with inspectors and dock neighbors.

- Keep spill kit items nearby: absorbent pads, socks, and a small trash can with lid. If a bund breaches, you can close it fast.

- Take photos of your containment before and after—useful for your records and any compliance questions.

Final checks before coating:

- Run your palm over the surface. It should feel even, not slick or greasy, with consistent dullness for paint or uniform satin for polish prep.

- Tape a 6-inch square and do a light solvent wipe. If the towel picks up color, there’s still residue—re-wash that area.

- Read the coating tech sheet for recoat windows. Wet sanding often allows quicker turnaround since surfaces are cooler and cleaner.

Wet Sanding vs. — Video Guide

If you’re weighing wet sanding against dry for oxidation removal and bottom prep, this short walk-through by a marine detailer breaks down the trade-offs in plain language. He shows how wet sanding keeps the surface cooler, reduces loading, and captures the dust as slurry—especially useful when dealing with chalky gelcoat or sunburnt topsides. You’ll see pass patterns, pressure cues, and when to swap grits to keep the cut efficient.

Video source: Wet Sanding vs. Dry Sanding Explained | Boat Detailing Tips

60 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (50-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Extra-coarse Silicon Carbide abrasive for rapid stock removal and reshaping. Excels at stripping paint, smoothing rough lumber, or eliminating heavy rust on metal surfaces. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Is wet sanding allowed in most boatyards?

A: Many yards prefer it because it controls dust, but they often require containment, PPE, and proper slurry disposal. Always check and show your plan before you start.

Q: What grit should I start with on antifouling?

A: For scuffing between coats, 120–180 wet is enough. For controlled removal, start at 80–100. Do a small test patch to confirm the removal rate before committing.

Q: Do I still need a respirator if I’m wet sanding?

A: Yes. Wet sanding minimizes airborne dust, but residues and splash can still expose you to toxins. Wear a P100 respirator, gloves, and eye protection.

Q: Can I wet sand gelcoat without risking burn-through?

A: Use higher grits (800–1500), keep the pad flat with light pressure, and work in short zones. Inspect often with raking light. If edges or corners thin, switch to a hand block.

Q: How do I know the surface is ready for new paint?

A: It should be evenly dulled with the target profile (e.g., 120–180 for antifouling), clean of residue, and fully dry. Do a tape-and-wipe check—if the wipe stays clean, you’re ready to coat.