Choosing Ceramic vs Silicon Carbide Sandpaper

You can hear it before you see it: the sander spins up, the deck light pools across a panel, and the first passes scratch a story into the surface. On a chilly Saturday morning, I’m in a small body shop with two stacks on the cart—one ceramic-oxide disc set, one pile of silicon carbide sandpaper sheets. The job is a split personality: strip rust from a welded bracket, level high-build primer on a fender, then color-sand a fresh clear coat. The wrong abrasive wastes time and ruins finish; the right abrasive turns minutes into clean geometry and predictable gloss. And the smartest choice changes as the substrate, coating, and workflow change.

There’s a temptation to think “grit is grit,” but cutting mechanics differ. Two P220 sheets can generate wildly different scratch shapes, heat, and dust loading. On tough, ductile materials (stainless, nickel alloys, hardwood end grain), ceramics micro-fracture under pressure, renewing sharp points and resisting heat. On brittle surfaces (glass, stone, cured clear coat), silicon carbide excels by cleaving cleanly and shedding debris when run wet. Choosing well means mapping abrasive behavior to material response, and knowing where speed, heat, and pressure intersect with consistent finish quality.

You feel the difference under your fingertips: ceramic’s steady pull and long life versus SiC’s crisp initial bite and glass-smooth scratch in wet work. The discipline is simple to state: decide for the substrate, then commit to the workflow—dry versus wet, pressure range, tool speed, grit ladder, and change intervals. Done right, you land on flat, uniform cuts with minimal rework and no surprise burn-throughs.

Quick Summary: Use ceramic abrasives for high-pressure cutting on tough, ductile substrates and coatings; use silicon carbide sandpaper for wet finishing on brittle materials, clear coats, and precision scratch refinement.

Material science beneath the grit

Ceramic alumina and silicon carbide are both “ceramic” in the broad sense, yet they behave differently at the point of contact. The differences start at microstructure and play out as cut rate, heat resilience, and scratch morphology.

Ceramic alumina is engineered as microcrystalline sintered alumina. Under load, it micro-fractures—controlled, fine-scale breakage that refreshes cutting edges without catastrophic grain failure. That self-sharpening is pressure-dependent: you need a threshold of contact stress to activate it. As a result, ceramic shines in high-pressure sanding and grinding on ductile, high-tensile materials such as carbon steel, stainless, and nickel-based alloys. It tolerates heat, resists dulling, and often displays a longer useful life per disc at the same grit than conventional fused aluminum oxide or SiC.

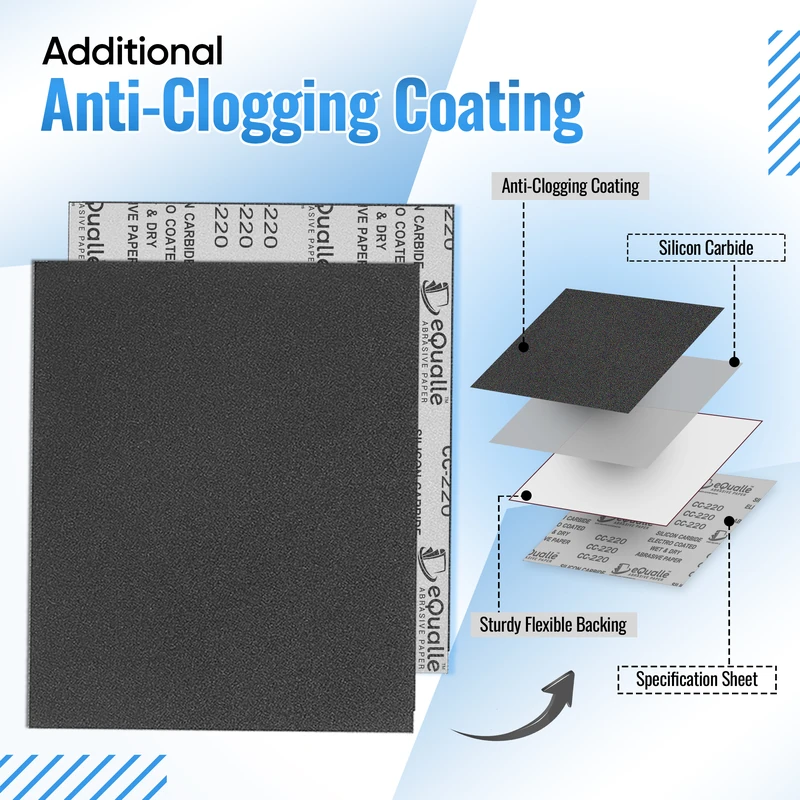

Silicon carbide, by contrast, is very hard and quite brittle, with a sharper initial geometry. It cuts aggressively on first contact and excels at shearing hard, brittle surfaces—glass, stone, ceramics, and fully cured automotive clear coat. Because SiC fractures more readily, it benefits from lubricated environments; in wet sanding, the water carries swarf away, cools the interface, and allows the paper to keep cutting with less loading. The resulting scratch tends to be crisp and shallow for a given grit, which is exactly what you want when refining finishes before buffing or recoating.

Thermal behavior matters. On metals and tough plastics, heat invites pigtails and smears; ceramics resist that more effectively. On finishes and brittle media, heat is the enemy of clarity and can soften binders—SiC, especially in waterproof backings, mitigates this under wet conditions. Understanding these traits lets you pick by outcome: long-life heavy cut versus precise, low-depth scratch refinement.

Workflows for predictable stock removal

Abrasive choice only pays off when the workflow supports it. Three controls dominate results: pressure, speed, and lubrication. Manage these intentionally and your scratch pattern becomes predictable.

Pressure. Ceramic abrasives need enough pressure to trigger micro-fracture and maintain fresh edges. If you feather-touch ceramic on stainless, it glazes and skates. Aim for firm, even pressure with a stable pad and full face contact—particularly at coarse to mid grits (P60–P240). Conversely, silicon carbide performs best at moderate pressure, especially when wet, to avoid chunking grains and deepening scratches.

Speed and stroke. On random orbit tools, orbit diameter and OPM work with grit to set aggressiveness. For ceramic at coarse grits on metal, higher OPM (8–12k) with a 5–8 mm orbit speeds removal. For SiC wet work on clear coat, back off to 5–8k OPM with short orbits to stabilize the scratch field. Keep the pad flat; toeing-in edges overheats, digs, and creates non-uniform scratches regardless of abrasive.

Lubrication. Use water with a few drops of surfactant for wet SiC sanding. The surfactant reduces surface tension, improves flush, and minimizes hydroplaning. For ceramic dry work on metals, dust extraction and stearate-coated grains help reduce loading; avoid wetting unless the product is rated for it, as some ceramic discs use backings and bonds that are not water-tolerant.

Grit ladders and change intervals. Map your path: coarse establish, mid refine, fine finish. Typical metal leveling might run P80 → P120 → P180 → P240 with ceramic, then switch media only if you’re transitioning to a brittle topcoat. Clear coat refinement might go SiC wet P1000 → P1500 → P2000 → P2500. Change discs proactively—ceramic when the cut slows (not when it smears), SiC when the sheet loads or loses sharpness.

Heat management. Feel the panel. If it’s hot to the touch, pause. Ceramics tolerate heat but still transmit it; coatings soften and smear if overheated. Stop pigtails before they start by keeping fresh interface pads and clean air paths.

Executed consistently, these controls turn your abrasive selection into a repeatable process rather than a guess.

According to a article

When ceramic beats silicon carbide sandpaper

The simplest rule: pick ceramic when the substrate fights back. If the material is tough, ductile, or heat-sensitive under load, ceramic’s self-sharpening grain and superior thermal endurance deliver faster stock removal and steadier scratch depth.

Choose ceramic over silicon carbide sandpaper when:

- You’re leveling or deburring high-tensile metals: carbon steel, stainless, tool steels, and nickel alloys. Ceramic maintains edge integrity under pressure and heat, cutting cleaner without glazing.

- You need to remove welds, scale, or mill marks where aggressive, uniform removal is required. Ceramic’s micro-fracture behavior keeps the cut rate high as the disc wears.

- You’re working tough polymers and composites that smear with heat: glass-filled nylon, UHMW-PE, carbon fiber laminates in early stages. Ceramic resists heat buildup and reduces resin streaking at appropriate speeds.

- You’re flattening hardwoods or dense end grain. While both grains will cut, ceramic maintains a steady bite and resists loading, especially with a dust extractor and open-coat design.

There are caveats. On delicate coatings and brittle media, ceramic can cut too deep and build heat that lifts edges or prints through. For cured automotive clear coat, gelcoat, glass, stone, and epoxy top layers at finishing grits, SiC wet dominates. SiC produces a narrower scratch for the grit size and clears swarf in water, which prepares the surface for compounding without deep grooves that require extra correction.

A hybrid workflow often wins: begin with ceramic to correct shape or remove defects rapidly (for example, leveling orange peel in primer at P180–P320), then transition to SiC wet for topcoat refinement (P1000 and above). The transition point is practical: switch as soon as you’re done with high-pressure bulk removal and ready to control scratch optics.

Surface prep on paints, gelcoats, and epoxy

Coatings behave differently than metals and bulk plastics; binders soften with heat and clog abrasives, and optics matter. For finishes where you ultimately expect gloss, your choice of grain is a choice about scratch architecture.

For primer and high-build surfacers, ceramic at P180–P320 is efficient for leveling. Use a medium interface pad to follow gentle contours without bridging lows, maintain even pressure, and keep your vacuum extraction on to prevent packed dust from smearing. Guide coats (dry powder) help visualize scratch depth and remaining texture; a uniform removal of the guide coat indicates flatness.

Once you approach color or clear, shift to silicon carbide sandpaper and go wet. SiC’s brittle grains slice without smearing and shed worn edges into the slurry. Typical clear coat refinement steps: P1000 to knock texture, P1500 to remove P1000 scratches, P2000 to remove P1500, and optionally P2500–P3000 if you want faster buffing with a fine compound. Keep the surface uniformly wet; a light surfactant in the water improves flushing and reduces random deep scratches caused by trapped grit.

Epoxy and gelcoat demand temperature control. If you’re leveling an epoxy primer or fairing compound, ceramic at mid grits works well—as long as you manage heat and avoid overworking edges. For fully cured gelcoat finishing, SiC wet outperforms: its sharper geometry and slurry flush avoid clogging, and the resulting scratch is easier to bring to gloss.

A note on interfaces and pads: firm pads produce flatter results but transmit heat; soft pads conform to curves but can round edges and unevenly load. Match pad firmness to the stage—firmer for early leveling with ceramic, softer for final SiC finishing on complex shapes. This balance keeps the scratch field even and prevents breakthrough on high spots.

Practical tips and grit mapping

Translate theory into repeatable moves with crisp, material-specific practices.

- Set pressure thresholds. For ceramic at P60–P240 on metals, target firm hand pressure (roughly 3–5 kg over a 125 mm pad) to trigger micro-fracture without stalling the tool. For SiC wet on clear coat, lighten to 1–2 kg; let the grit and slurry work.

- Control speed and orbit. Use 8–12k OPM with 5–8 mm orbit for ceramic heavy stock removal; drop to 5–8k OPM with 2.5–5 mm orbit for SiC finishing to keep the scratch short and consistent.

- Switch media at the right moment. Run ceramic until shape is correct and the defect field is gone, then swap to SiC when the task becomes optical (scratch visibility) rather than geometric (flatness). Don’t “polish” with ceramic at fine grits on sensitive coatings—go SiC wet instead.

- Manage slurry and dust. For SiC wet, add two drops of dish soap per liter of water. Wipe and refresh every 3–5 passes to prevent recutting loose grit. For ceramic dry, clean discs with a crepe block or change early to avoid glazing.

- Map your grit ladder by substrate:

- Metals: Ceramic P80 → P120 → P180/240; finish with non-woven or ceramic P320 if painting, then primer.

- Primers: Ceramic P180 → P240 → P320; then SiC wet P600/P800 if moving to color.

- Clear coat: SiC wet P1000 → P1500 → P2000 → P2500/P3000 before compound.

- Composites: Ceramic P120 → P180 for fairing; SiC wet P400/P600 for gelcoat prep.

Consistency here is ROI: fewer discs, fewer surprises, and a finish that behaves in the booth and on the buffer.

Color Sanding Aluminum — Video Guide

A useful visual comparison pits aluminum oxide against silicone (silicon) carbide for color sanding, asking which abrasive wins on automotive clear and single-stage paint. The demonstration walks through cut speed, scratch depth, and post-sanding clarity, highlighting how wet SiC refines the finish with minimal clogging while general-purpose aluminum oxide struggles to deliver the same optical quality.

Video source: Color Sanding Aluminum Oxide Vs Silicone Carbide Sandpaper - Which Is Best!? (Yes, there Is a Best)

60 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (10-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Extra-coarse Silicon Carbide abrasive for rapid stock removal and reshaping. Excels at stripping paint, smoothing rough lumber, or eliminating heavy rust on metal surfaces. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: When should I switch from ceramic to silicon carbide during a job?

A: Switch as soon as the task shifts from bulk correction to optical control. After ceramic has established flatness (e.g., primer leveled at P240–P320), move to silicon carbide sandpaper for wet refinement on color or clear so you build a shallow, uniform scratch that buffs quickly.

Q: Can ceramic abrasives be used wet like SiC?

A: Some ceramic products are rated for wet use, but most ceramic discs are optimized for dry cutting with dust extraction. SiC benefits markedly more from wetting because it sheds swarf into the slurry and maintains a finer effective scratch. Check the manufacturer’s rating before introducing water to ceramic discs.

Q: How do I prevent pigtails and random deep scratches?

A: Keep the pad and interface clean, maintain consistent pressure and full pad contact, and match grit to the task. For wet SiC, flush often and wipe the surface between passes. For ceramic, replace discs at the first sign of glazing and ensure vacuum holes are clear to avoid entrapped debris.

Q: What grit ranges best showcase ceramic vs SiC strengths?

A: Ceramic excels from coarse through mid grits (P36–P320) on metals, composites, and primers where high pressure and heat are present. SiC shines at fine grits (P600–P3000) in wet sanding of clear coats, gelcoats, glass, and stone, producing a tight, shallow scratch for fast polishing.

Q: Is silicon carbide appropriate on aluminum and soft metals?

A: It can cut, but loading is common. For aluminum and soft, gummy metals, ceramic or specialized non-loading aluminum oxide with stearate is usually better for dry work. If you must use SiC, run wet and clean frequently to mitigate clogging.