Cork vs Rubber Sanding Block: Even Pressure, Better Finish

You feel it before you see it: the drag of abrasive across primer, the subtle chatter in your wrist, the way dust plumes differently at the edge than it does in the center. The project might be a cabinet door with raised panels, an automotive quarter panel wearing its first coat of high-build, or a mid-century tabletop with a veneer you refuse to risk. Regardless of the substrate, the instrument in your hand—a sanding block—is the difference between flat and faceted, between crisp and crowned. When the pressure is wrong, the finish is wrong. The telltale symptoms appear later: telegraphed low spots under gloss, rounded edges where a sharp reveal should live, swirl hazing that refuses to die at the next grit.

In the shop, choice is a discipline. Do you reach for cork or rubber? Both promise even pressure, both promise control. But they behave differently in your hand and on the surface. Cork offers a forgiving face that conforms without collapsing, transmitting a broad, uniform pressure profile. Rubber, depending on durometer, can be firm and decisive, locking a plane into flatness and suppressing chatter. Over a long session, those differences compound into measurable outcomes: more consistent scratch depth, better grain reveal, cleaner edge retention, less rework. Picking the right block is not a matter of preference; it’s a workflow decision that governs abrasive performance and the data you can trust from your surface.

Let’s map the mechanics behind cork versus rubber, then translate that into a repeatable sanding workflow that advances from shaping to surfacing with minimal risk of overcutting. We’ll test pressure uniformity, pair blocks with appropriate grits and backings, and build ergonomics into the process so your hands aren’t the variable the finish inspector finds.

Quick Summary: Choose cork when you need forgiving conformity and scratch blending; choose rubber when you need firmness, flatness, and edge discipline—then match each to the right grit, backing, and stroke pattern for even pressure and a predictable finish.

Why even pressure governs the finish

Even pressure is the control variable that keeps scratch depth predictable and topography stable across passes. With hand sanding, the interface—your block—redistributes load from your fingers to the abrasive. A good block equalizes peaks and valleys; a poor one prints your grip into the surface.

The physics is straightforward. Local pressure (P) drives material removal rate (MRR); for a given grit and abrasive mineral, MRR is roughly proportional to P up to a threshold where grain fracture and loading alter the curve. On a compliant substrate (wood, body filler, primer), uneven pressure cuts deeper at high spots, lifts at lows, and rounds edges by concentrating load at the radius. On a rigid substrate (metal), excessive local pressure can glaze the abrasive or create deep furrows that are costly to chase out.

Block compliance controls contact area. A too-soft interface expands the footprint, lowering pressure but smearing scratches and telegraphing underlying waviness. A too-hard interface focuses the load, yielding fast, flat cutting—but it also raises the risk of digging at edges and bridging over shallow lows. The “evenness” we want is not equal force everywhere; it’s controlled pressure distribution appropriate to the surface and task.

Diagnostic tools help quantify this. Lightly pencil a crosshatch grid across the work. After five strokes with a consistent pattern, read the removal map. Uniform fade indicates even contact; patchy erasure suggests pressure bias. For more rigor, place carbon paper under a sacrificial sheet and press the block to capture a pressure imprint. Cork typically produces a smooth gradient; a firm rubber block shows a crisp, rectangular footprint with slightly higher edge pressure. Neither is “better” globally—each is optimal for different phases of the workflow.

In practice, even pressure translates to these outcomes: fewer grit steps (because scratches are uniform), less need for filler or spot priming, crisper edges where design intent demands it, and surfaces that accept topcoats without surprise. The right block makes even pressure repeatable.

Selecting a sanding block by durometer

When we say cork versus rubber, what we’re really choosing is interface stiffness—measured for rubber as Shore A durometer and experienced for cork as compressive compliance. A typical rubber sanding block ranges from Shore A 40 (semi-flexible) to Shore A 70 (firm). Cork doesn’t map cleanly to Shore scales, but as a rule it compresses modestly and rebounds slowly, spreading load while damping vibration.

Use a firmer rubber sanding block (Shore A 60–70) when you need to preserve flatness and geometry:

- Leveling wood panels after glue-up with 80–120 grit where flat is non-negotiable.

- Blocking automotive high-build primer with 180–320 grit to eliminate orange peel and guide-coat lows.

- Dressing epoxy fills or polyester body filler where a rigid interface prevents “dishing.”

Opt for a semi-flexible rubber block (Shore A 40–50) when surfaces include gentle contours and you want pressure stability without telegraphing finger pressure. These shine on cabinet rails/stiles, curved moldings, and rolled fenders.

Choose cork when you need subtle conformity and scratch blending:

- Final passes on veneer with 220–320 grit, where the goal is uniform reflectivity without cutting through.

- Scuff-sanding between coats of paint or lacquer, where a forgiving interface maintains film build.

- Edge-safe work around profiles where a firm block would cut a flat into a radius.

Cork’s microcellular structure dampens high-frequency chatter. This matters with finer grits (P240 and up), where inconsistent pressure can create patchy sheen (“holidays”) that only appear under raking light. Rubber’s advantage is shape fidelity; its rebound is faster and its pressure curve steeper, so it “decides” the plane and holds it.

Grip and ergonomics enter the equation too. Rubber blocks typically have molded contours, allowing better torque control and reduced hand fatigue. Cork blocks are lighter and transmit more tactile feedback—you feel the surface through them—useful when hunting highs or feathering edges.

A practical way to decide: align block stiffness with the tolerance of the geometry. If you measure flatness with a straightedge and feeler gauge, reach for firm rubber. If you assess by gloss uniformity and tactile smoothness, cork will often get you there more safely. Many pros keep both, swapping as they move from shaping to surfacing.

Cork vs rubber: contact mechanics

Contact mechanics explains why cork and rubber leave different signatures on a surface. Under load, a firm rubber block with a thin paper backing establishes “planar contact”—a broad, flat footprint that cuts high spots aggressively and ignores lows until they rise to the plane. It is a mechanical reference, similar to a hand plane’s sole: the flatter the block, the flatter the result.

Cork behaves as a compliant foundation. Its cellular matrix compresses locally around peaks, increasing local contact area (reducing pressure) while maintaining contact in adjacent lows (raising pressure slightly there). This self-leveling tendency blends scratches and reduces the “striping” you can see after staining or under gloss when a rigid interface has cut in discrete tracks.

On edges and corners, the difference is stark. Rubber tends to concentrate stress at edges, particularly if the paper wraps around to the side. This is excellent for crisping a chamfer or defining a reveal but risky on veneer or thin film builds. Cork, because of its compliance, diffuses that edge pressure, making it the safer choice for edge preservation.

Backing strategies amplify or moderate these effects:

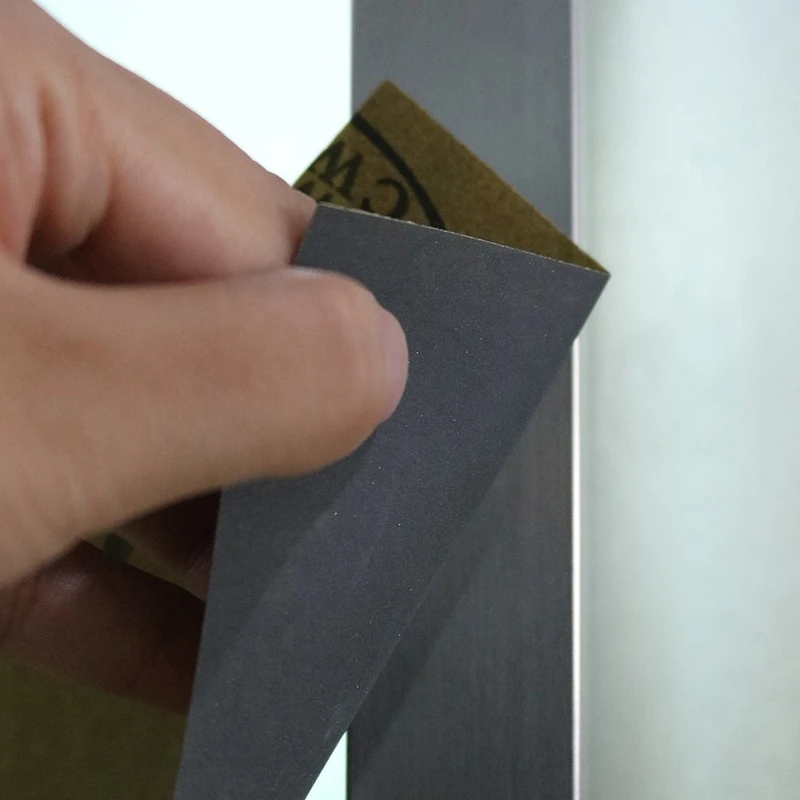

- Bare block with wrapped paper: maximizes the block’s native stiffness profile. Good for aggressive leveling with rubber or high feedback with cork.

- PSA (pressure-sensitive adhesive) sheets: improve coupling, reduce slip, and sharpen cut. Pair PSA with rubber when uniformity is critical.

- Hook-and-loop interface: adds a thin foam layer, increasing compliance. This effectively “softens” a firm rubber block and can make cork feel too soft; reserve H&L for contoured work or final blending with P320+.

A quick shop test illustrates the mechanics. Apply a guide coat (dry powder or light mist of contrasting paint) and take ten overlapping strokes at 45 degrees with each block. The rubber block will erase the guide coat in a crisp, planar pattern and leave untouched lows until subsequent passes. The cork block will show a more diffuse removal, kissing into lows earlier and leaving fewer hard transitions.

Noise and vibration are also signals. Firm rubber transmits a consistent, low chatter that tells you when you’re on plane. Cork dampens that chatter; instead, you’ll feel subtle drag variations as the surface evens out. With practice, these feedback modes become reliable indicators of when to stop and advance grits.

Workflow: grit sequences and coupling

A block is one variable; grit, abrasive mineral, and coupling method complete the system. If you want even pressure to translate into even cutting, pair each block type with an appropriate grit range and backing.

Woodworking example (maple tabletop, film finish):

- Shaping and flattening: Rubber block, Shore A ~60, P80 → P120. Use wrapped paper or PSA to keep the interface rigid. Take diagonal passes, then with grain, checking with a straightedge.

- Refinement: Switch to cork with P150 → P180. The cork will blend scratch transitions and reduce edge aggression.

- Pre-finish: Cork with P220 → P320 as needed for film prep. A thin H&L interface can help follow subtle figure without faceting.

Automotive primer blocking:

- Leveling primer: Firm rubber block, P180 → P240, using a guide coat on each step. Long strokes across the panel’s crown, alternating directions.

- Refinement: Semi-flex rubber or cork with P320 → P400 to unify the scratch and preserve panel curvature. Use dry powder guide coat to verify uniformity before sealer.

Paint scuff between coats:

- Cork with P320 → P400 for waterborne; P400 → P600 for solvent-borne. Light pressure, large overlapping circles or with-the-grain strokes. The goal is mechanical adhesion with minimal film removal.

Coupling matters. PSA sheets tie the abrasive tightly to the block, preventing slip and maintaining true pressure distribution—great for flat work and rubber blocks. Hook-and-loop introduces compliance; it’s beneficial when you need forgiveness or are chasing micro-contours. Open-coat aluminum oxide papers manage dust better on wood; stearate-coated sheets resist loading in painted and resinous substrates. Ceramic or silicon carbide can be overkill with hand sanding unless you’re on hard coatings; they cut fast but can dig if pressure spikes.

According to a article, rubber interfaces tend to deliver firmer, more even pressure with reduced vibration—attributes that align directly with the “flat first, blend second” approach outlined here.

Process control ties it all together:

- Always mark the surface with a pencil grid or guide coat before each grit.

- Sand with a consistent stroke length and overlap (50–70%), varying direction at each grit step to reveal residual scratches.

- Vacuum or wipe clean between grits; dust acts like rogue coarse particles and can seed deeper-than-expected scratches.

- Advance grits by typical multipliers (P80 → P120 → P180 → P240 → P320). Skipping more than 1.5× can leave subsurface scratches that telegraph later.

Ergonomics, dust, and consistency controls

Even pressure is not just a materials property; it’s also an operator habit. The way you hold the block, manage dust, and structure passes can either stabilize or destabilize your results.

Ergonomics first. A block that fits your hand reduces micro-tilt and the urge to “thumb press” a problem area. Rubber blocks often feature contoured grips that lower fatigue over long strokes and help keep wrists neutral. Cork blocks, while simpler, are lighter and transmit surface feedback effectively; pairing them with a wraparound paper that adds texture can improve grip. For large flats, consider a longer block (8–16 inches). Length averages highs and lows; the longer the block, the less it will follow small undulations. Reserve shorter blocks for tight areas and localized defects.

Edge management is a repeatable technique. Chamfer the paper’s edges slightly to reduce cutting aggression at the paper’s boundary. Avoid wrapping paper tightly around sharp block edges when working near delicate corners; instead, flush-trim the paper to the block face so the edge isn’t a cutting tool. For profiles, add a thin foam interlayer to a rubber block or switch to cork to diffuse edge pressure.

Dust control matters for both health and surface quality. Dust between the block and work acts like random grit, creating scratches that ignore your grit step strategy. Vacuum the surface frequently, blow off the paper, and consider anti-clog papers with stearate for paints and resins. For wet sanding (common on cured lacquer or automotive clears), cork excels—its damping is pleasant with water, and the slurry helps refine the scratch. Keep the block face clean; spent grains fracture and can scratch unpredictably.

Build consistency with measurable checks:

- Use a raking light to inspect scratch uniformity. If sheen is patchy, pressure isn’t even.

- Log your grit sequences and block choices for recurring projects; your future self will thank you.

- Replace paper on time. When cutting slows or dust smears, the paper is glazed and you’ll start pressing harder—ruining your pressure discipline.

Actionable tips:

- Do the pencil grid test before each grit. If the pattern disappears uniformly in 10–15 strokes, your block choice and pressure are correct; if not, adjust block stiffness before changing grits.

- For fragile veneers, stack a cardstock shim between paper and cork to stiffen just enough to prevent wave imprinting without losing forgiveness.

- On long panels, use a two-hand, push–pull stroke with a slight diagonal bias; it reduces local pressure spikes and averages your body movement.

- When blocking primer, always use a guide coat and a firm rubber block first; only switch to cork after the guide coat erases uniformly to avoid chasing lows prematurely.

- If edges are thinning, switch to cork and mask edges with low-tack tape to mechanically limit pressure and film removal at the boundary.

Are you using — Video Guide

A concise video breakdown explores when to use rigid, semi-rigid, flexible, or contoured blocks, with practical scenarios for each. It clarifies how block stiffness influences scratch depth, flatness, and edge safety, and shows how to select a block that matches the surface geometry and task.

Video source: Are you using the wrong kind of sanding block? What you need to know...

220 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (10-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Refined medium-fine abrasive for final surface leveling on primed or sealed materials. Great for smooth touch-ups before finishing. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: When should I use cork instead of rubber?

A: Use cork when you need subtle conformity and blending, such as final passes on wood at P180–P320, scuff-sanding between coats, or working near edges and profiles where a firm block might overcut. Cork’s damping reduces chatter and helps even sheen.

Q: What durometer rubber block is best for leveling?

A: For flatting panels or primer, a firm rubber block in the Shore A 60–70 range maintains plane and resists following small waves. Use Shore A 40–50 when the surface includes gentle curves and you want controlled flexibility.

Q: How do I verify even pressure during sanding?

A: Mark the surface with a pencil grid or guide coat and take a set number of strokes. Uniform erasure indicates even contact. You can also use a carbon paper imprint to visualize pressure distribution across the block face.

Q: Should I use PSA, hook-and-loop, or wrapped paper?

A: PSA provides the most rigid coupling—ideal for firm rubber blocks and flatting operations. Hook-and-loop adds compliance, useful on contours or with finer grits. Wrapped paper is versatile and preserves the native feel of the block; chamfer edges to reduce cut aggressiveness.

Q: Why do edges burn through or round over?

A: Edges concentrate pressure, especially with firm blocks and paper wrapped around corners. To prevent this, trim paper flush at the block edge, reduce pressure at edges, switch to cork for blending, or mask edges temporarily to protect film build.