Mastering sandpaper grit for deep scratch removal

The first pass felt promising. Under the raking light, your tabletop—once scored by a moving box staple—looked flatter after a few steady minutes with the sander. But as you wipe the dust and the surface flashes under a shop lamp, new lines appear, marching in a tidy, parallel pattern. You didn’t make the damage worse; you simply revealed the truth. Deep scratches are not single defects; they’re profiles with depth, flanks, and torn fibers or gouged metal. Managing that geometry is why sandpaper grit selection and step-down discipline matter as much as the tool in hand.

Whether you’re reclaiming a hardwood desk, blending a scratch in a clear-coated fender, or restoring a hazed headlight, the path to clarity is the same: progressively refine the scratch pattern so each subsequent abrasive removes the previous one’s “signature” completely. The rhythm is technical, not artistic. It’s about choosing the right starting grit to fully reach the bottom of the deepest defect, then applying controlled changes in pressure, pad compliance, motion, and grit spacing to exit cleanly at the finish you need. When you understand the interaction between grit size, backing stiffness, and substrate hardness, you stop chasing ghosts and start hitting finish thresholds on schedule.

If you’ve ever jumped from an aggressive cut straight to a polish, you’ve seen the cost: lingering troughs that a compound cannot bridge, or swirls that blossom only after stain or clear magnifies the micro-topography. The fix is not more passes with the same sheet—it’s a disciplined sequence that fully replaces one scratch family with a finer one, confirmed by inspection, before you proceed. This article distills those step-down rules into practical workflows across wood, metal, and plastics, so you get from damage to defect-free with fewer surprises and less material loss.

Quick Summary: Choose a starting grit that fully reaches scratch depth, then reduce grit incrementally (about 1.4–1.6× jumps), replacing each scratch pattern completely before moving on.

Why deep scratches persist

A “deep scratch” isn’t just a thin line; it’s a channel whose depth and flank angle depend on the original defect (a dragged screw, a grit particle, a burr) and the substrate (cellular wood grain, ductile metal, or viscoelastic plastic). When you sand, you’re not polishing the surface; you’re planing down the surrounding terrain until the floor of that channel disappears. If your abrasive can’t reach the bottom, it can only shine the sidewalls. Under liquid or finish, those sidewalls reflect as persistent lines.

Three mechanisms make deep scratches linger:

- Insufficient depth reach: Starting too fine leaves the trough intact. Finishing passes only “dress” the edges, so the line survives.

- Scratch stacking: Skipping too many grits creates intersecting scratch families of different depths; finer abrasives reduce peaks but cannot erase the valleys left by coarse steps.

- Heat and loading: On metal and plastics, heat softens the substrate and loads the abrasive, rounding cutting edges and smearing material. The tool “glides,” failing to cut to the required depth.

Scratch removal is a depth budget problem. Approximate abrasive particle size (FEPA P-scale) corresponds to scratch potential: P80 ~201 µm particles with typical scratch depths up to roughly 10–30 µm depending on backing stiffness and pressure; P400 ~35 µm particles, scratch depths roughly 2–6 µm. While the exact numbers vary, the principle holds: each step must be able to remove at least the prior step’s deepest valleys. If you leap from P120 to P400, P400’s maximum removal depth may be insufficient to obliterate P120’s troughs in a reasonable time, especially on hard coatings.

Substrate matters. Wood’s earlywood/latewood density swing makes end grain behave like a field of straws; coarse scratches “telegraph” even after planing. Metals tend to smear and form built-up edges, creating secondary scratches if the abrasive loads. Plastics can melt, rounding over scratch tips so they become diffuse, then reappear after the surface cools and shrinks. That’s why pressure discipline, dust extraction, and fresh abrasives are non-negotiable for scratch erasure.

Step-down strategy by sandpaper grit

The governing rule: the next grit must fully remove the previous scratch pattern, with controlled, modest jumps in particle size. In practice, 1.4–1.6× grit steps (by number) are efficient without risking lock-in. On FEPA P-scale sheets and discs, this typically looks like:

- Coarse leveling: P80 → P120 → P150/180

- Refinement for bare wood finishing: P180 → P220 → P320 → P400 (stop at P180–P220 before stain for most woods; refine to P320–P400 for clear finishes)

- Refinement for coatings: P220 → P320 → P400 → P600 → P800 (primer/surfacer sanding)

- Pre-polish for clears/plastics/metals: P800 → P1000 → P1500 → P2000 → P3000 foam/film

If you’re erasing a known defect, select a starting grit that can cut to the bottom of that defect in a few passes. A linear 200–300 µm-deep gouge in hardwood typically demands P80 or P100 to flatten promptly; a shallow clear-coat scuff on a car might start at P1500 or P2000.

Practical sequences:

- Hardwood tabletop gouge: P80 (level) → P120 → P180 → P220. If clear-finishing, continue P320 → P400. Re-establish flatness with a hard block early; switch to a softer pad for refinement.

- Bare metal (aluminum/steel) scratch prior to primer: P120 → P180 → P240 → P320 → P400. Avoid dwelling on edges; use interface pads to prevent burn-through.

- Headlight lens or bumper clear: P800 (if deep) → P1000 → P1500 → P2000 → P3000, then compound. Ensure water flush to control heat; plan for a UV-stable topcoat on polycarbonate lenses.

Actionable tips:

- Keep grit jumps conservative when leaving a coarse regime. From P80, don’t leap beyond P150; from P220, you can jump to P320 or P400 safely if inspection confirms removal.

- Replace paper/discs at the first sign of loading or drop in cut. A dull P800 behaves like a random scratch generator that won’t reach depth.

- Cross-hatch 10–15° between steps. Changing angle makes the prior pattern easy to see and confirms full replacement.

Terminology note: FEPA P-grits (P400, P800) are not identical to ANSI/CAMI numbers (400, 800). When mixing brands, check the size chart, and favor P-marked abrasives for consistent step-down planning.

Abrasive types and backing choices

Your abrasive chemistry and backing stiffness control both removal rate and scratch morphology. Choose them intentionally:

- Aluminum oxide (AlOx): Tough, friable enough to micro-fracture and stay sharp on wood and many metals. Excellent general-purpose choice for P80–P400 leveling.

- Silicon carbide (SiC): Sharper, more brittle, excels in wet sanding, plastics, composites, and between-coats on finishes. Preferred for P800–P3000 and for leveling hard coatings or glass-like plastics.

- Ceramic alumina and zirconia: High-pressure, cool-cutting grains ideal for heavy stock removal on metals. Often overkill for finish sanding but superb when you must erase deep steel scratches quickly.

Backing and coat:

- Paper vs film vs cloth: Film-backed abrasives deliver the most uniform scratch pattern at fine grits (P800+), essential before polishing plastics or clears. Paper-backed sheets are cost-effective for wood; cloth excels in belts and for contour work.

- Closed coat vs open coat: Open-coat leaves more voids between grains, reducing loading in soft woods and paints during coarse steps. Closed-coat cuts faster and leaves more uniform patterns at finer grits.

- Stearate loadings: Anti-clog coatings that reduce loading on paints and resins; helpful for between-coat sanding and plastics.

Interface and pad compliance:

- Hard blocks and hard backing pads keep surfaces flat and bring scratches to depth quickly—use them for the first one or two steps.

- Medium/soft interface pads conform to curves and reduce edge aggression—use them once the deepest troughs are gone to avoid “dishing” around defects.

Tooling parameters matter. Dual-action (DA) sanders with 5–7 mm orbits remove material faster but can create “pigtails” if dust is trapped or discs are worn. Use dust extraction—pigtails are micro-spirals that often survive several grit steps if not addressed early.

Inspection checkpoint: After each step, wipe with mineral spirits or water (compatible with substrate) and view under raking light at 30–45°. If any prior-angle scratches remain, do not step up. This is where many headlight and clear-coat attempts fail—ending at P2000 without complete P1500 removal leaves residual haze that compound cannot dig out efficiently. According to a article.

Workflow: wood, metal, and plastics

H3: Wood finishing workflow

- Assess depth and grain orientation. End grain magnifies scratch visibility; treat it as one to two grits coarser than face grain.

- Start aggressive enough to reach trough depth fast (P80–P120 for gouges). Use a hard, flat block to avoid sculpting a low spot.

- Step through P150/180 → P220 for stain prep. For clear finishes, continue to P320–P400 with reduced pressure. Vacuum between steps; dust under the pad seeds random deep scratches.

- Use a graphite or pencil “guide coat” scribble before each step; sand until all marks vanish uniformly. This verifies full pattern replacement.

H3: Metal prep prior to paint

- For steel or aluminum scratches, begin P120–P180 with a firm interface. Keep stroke time short on edges; mask sharp break lines to prevent burn-through.

- Move through P240 → P320 → P400. If priming high-build, you can stop at P320; if going to sealer or basecoat directly, refine to P400–P600 as specified by the coating.

- Control heat: Cool-to-the-touch is mandatory. If the surface warms, your disc is glazing instead of cutting. Swap discs early; wax-like loading indicates smearing.

- After primer, flatten with P400–P600 on a hard block; switch to P800–P1000 before color if directed by the paint system.

H3: Plastics and clear polymers

- Polycarbonate lenses and painted bumpers behave differently. Uncoated lenses need wet sanding with SiC film: P800 → P1000 → P1500 → P2000 → P3000 foam. Maintain a steady water film and rinse the pad often.

- Painted bumper repairs: Knock down filler and high spots at P80/P120 on a hard block; refine to P180/P220 before primer. After primer, step P320 → P400 → P600, then pre-scuff blend areas at P800–P1000.

- Plastics are sensitive to heat. Use light to moderate pressure and keep the abrasive moving. A foggy appearance after drying often means the prior grit wasn’t fully removed—repeat the last step until uniform.

Pro tips:

- On end grain, stop one grit coarser than face grain before stain to avoid over-burnishing and blotchy uptake.

- For lenses, always reapply a UV-stable clear; polishing alone restores clarity temporarily but invites rapid re-haze.

Inspection and finish prep

You can only manage what you can see. Build an inspection routine that quantifies readiness to step up:

- Raking light: Place a bright LED 18–24 inches above the surface, angled 30–45°. Rotate your viewing angle to confirm scratch direction and uniformity.

- Solvent or water break test: On bare wood or metal, a quick wipe darkens the surface and mimics the way finish will highlight valleys. Any linear features that persist need more work at the current grit.

- Guide coats: Use a powdered guide coat (or dry pigment) lightly over primer or filler. Sand until the powder disappears uniformly, proving flatness and full scratch replacement.

Micron thinking helps. Clear coats range 30–60 µm total on many automotive finishes. A P1000 scratch can be around 3–5 µm deep; a P400 scratch can exceed the available clear thickness. If you sand P400 into a finished panel, no amount of polishing will “fill” that valley without re-coating. The same logic applies to wood: burnishing to P600 on dense maple can close pores and cause finish adhesion or color issues; stopping at P180–P220 before stain leaves enough micro-tooth for even uptake.

Common error modes:

- Pigtails: Tiny spirals from DA sanders caused by debris or worn discs. They survive multiple grit steps and bloom under finish. Prevent with clean discs, vacuum extraction, and interface pads; remove by returning one or two grits coarser.

- Dishing: Over-sanding soft putty relative to surrounding metal/wood. Use hard blocks early and confine sanding to high spots.

- Edge burn-through: Edges cut faster; reduce pressure and increase pad compliance near edges, or mask them during early, coarse steps.

Actionable control checks:

- At each step, change sanding direction slightly and stop only when the prior angle’s scratches are completely gone.

- Use timed passes to avoid overworking: e.g., two slow cross-hatched passes per area, inspect, then decide to continue or step up.

Learn Plastic Bumper — Video Guide

A concise training video shows a blue plastic bumper being sanded with coarse abrasives, the surface deliberately scratched with 80-grit, and then filled and refined. The instructor demonstrates how aggressive grits rapidly level repairs and why stepping down is essential before priming. You’ll see angle control, block selection, and the transition from shaping to surfacing—exactly where many DIY jobs go wrong.

Video source: Learn Plastic Bumper Repair Vid 2/5: Sand & Fill

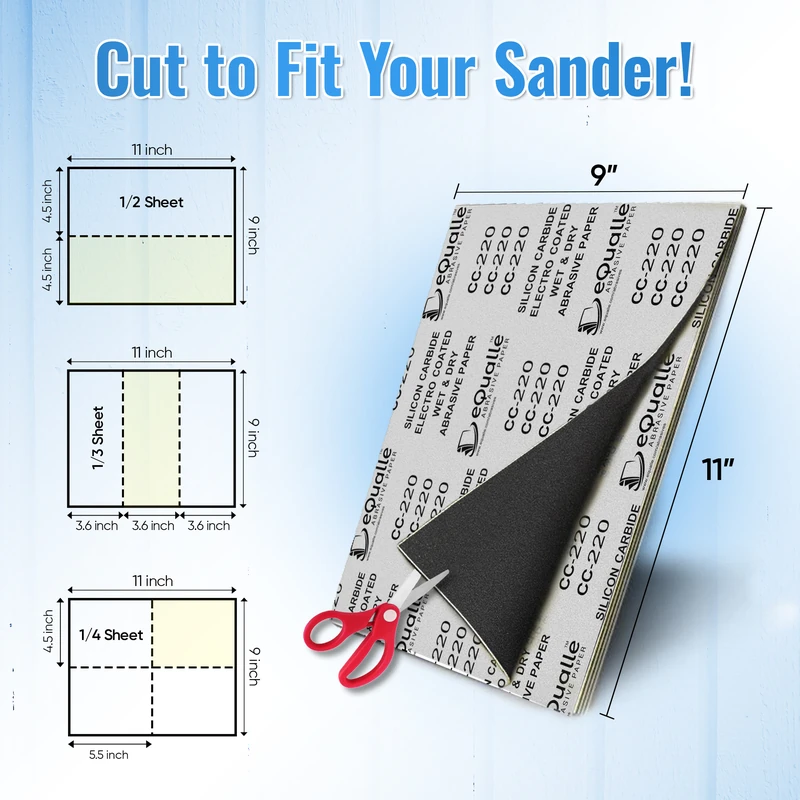

180 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (100-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Reliable grit for producing a uniform texture on wood, metal, or filler layers—often used before varnishing or applying topcoats. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: How do I pick a starting grit for a deep scratch?

A: Choose the coarsest grit that can reach the bottom of the deepest trough in a few passes: P80–P120 for significant gouges in wood or bare metal; P800–P1000 for clear plastics. If your first inspection still shows the original defect after two cross-hatched passes, you started too fine.

Q: What grit jumps are safe without locking in scratches?

A: Keep steps to roughly 1.4–1.6× in grit number (e.g., P120 → P180 → P240 → P320). Larger jumps risk leaving the prior valleys intact, forcing extra time or a return to the coarser grit.

Q: Can polishing compound remove P1000 or coarser scratches in clear coat?

A: Compounds remove only a few microns efficiently. They can clear P1500–P3000 patterns in most systems, but P1000 or coarser scratches often remain visible unless you sand through P1500–P2000 first.

Q: Should I sand wood beyond P220 before stain?

A: Usually no. P180–P220 preserves pore openness for even color. Dense woods may tolerate P320 with dye stains; however, over-burnishing can cause blotching and adhesion issues. For clear finishes, refine to P320–P400 after sealing.

Q: Why do “pigtail” swirls appear after I thought I was done?

A: They originate from debris trapped under a DA disc or from worn abrasive. Use dust extraction, clean discs, and inspect after each step under raking light. If you spot pigtails, drop back one or two grits and fully remove them before proceeding.