Ceramic Sanding Discs for Cooler, Cleaner Cuts

Late on a Saturday, the garage hums like a small factory. The goal is modest—deburr a few stainless brackets, flatten a maple cutting board, and knock down drips on a fiberglass canoe repair—but the reality is a stack of spent discs, a hot sander, and surfaces that look worse with every pass. You can smell scorched wood and feel the sander dragging as the face clogs with resin and dust. The disc you just installed is already glazed. It’s the kind of session that makes you wonder if sanding is a test of patience rather than a controllable, measurable process.

That was my recurring scene before I standardized on ceramic sanding discs. As a product engineer who runs controlled abrasive tests, I’ve come to accept that heat and loading are the real enemies—not the hardness of the work. Stainless, exotic alloys, dense hardwoods, and fiber-reinforced composites all share a behavior profile: they build heat at the interface, and they pack swarf into the abrasive face. When that happens, cut rate nosedives, the work burns or smears, and your productivity falls off a cliff.

The path out is part material science, part technique. Ceramic alumina grains fracture in a controlled way, exposing new sharp facets under load. Bond systems and topcoats are tuned to shed heat. Mesh or open-coat patterns keep the interface open enough for swarf and dust to evacuate. The result, when the disc, tool, and technique are matched, is a cooler interface, slower loading, and a finish that progresses predictably through the grit sequence.

In this review, I’ll break down how heat is generated, why loading accelerates it, what differentiates ceramic discs from other abrasives, and the test data that convinced me to change my standard kit. If your work includes stainless, hard maple, epoxy composites, or aluminum, you’ll get a practical playbook for cutting cooler with fewer disc changes—and a clearer ROI.

Quick Summary: Ceramic sanding discs self-sharpen under load, run cooler, and resist loading on tough materials when paired with proper dust extraction, pressure, and grit sequencing.

Why Heat and Loading Kill Productivity

When you press abrasive against a workpiece, almost all the energy you put in becomes heat. On tough materials—stainless steel, nickel alloys, end-grain hardwoods, and fiber-reinforced plastics—the thermal pathway is poor. Stainless has lower thermal conductivity than carbon steel, hardwood resin insulates, and composite matrices smear and trap heat. That heat does two things: it softens the resin bond of the disc, and it welds or smears swarf into the abrasive face.

Loading happens when chips (metal fines, wood resin, or composite dust) embed between grains and in the bond. The friction coefficient rises, sliding contact increases, and the disc shifts from cutting to rubbing. Once rubbing dominates, temperatures spike. You see it as color: steel straw-to-blue heat tint, wood brown scorch lines, or glossy polymer streaks on composites. You feel it as drag. You hear it as a muddy, lower-frequency whine from the sander.

Meanwhile, abrasives fail in two major modes: dulling and shedding. Aluminum oxide (AO) often dulls—the grains round over, the disc continues to rub, and heat grows. Zirconia alumina grains are tougher and fracture a bit better, but can still glaze on resinous materials. Resin bonds in low-cost discs may hit their glass transition temperature (think 90–120°C), soften, and further trap swarf. The cycle is self-reinforcing: more heat leads to more loading, more loading to more heat.

The path to cooler sanding is to maintain cutting rather than rubbing. That means sharp grain edges, controlled chip formation, open escape pathways, and a bond that survives the heat long enough to release dull grains and present sharp ones. The disc itself can help, but so can your setup: adequate dust extraction to remove fines, correct pad hardness to manage pressure and contact area, and a pass strategy that avoids stationary dwell. When those parts align, you break the heat-loading cycle and keep the interface in a stable, productive state.

How Ceramic Sanding Discs Stay Cool

Ceramic alumina is engineered to microfracture. Under normal grinding loads, these microcrystals chip at their edges, revealing fresh, sharp cutting faces. That self-sharpening behavior keeps the effective rake angle high and chip thickness controlled, so grain tips slice rather than plow. Less plowing equals less heat. The effect is most obvious on tough materials where conventional AO dulls quickly and zirconia begins to smear or glaze.

Two additional design choices in premium ceramic sanding discs further cut heat and loading:

- Resin bond and size coats: Heat-resistant resins and engineered size coats maintain integrity at higher interface temperatures. They release dull grains predictably instead of softening into a gummy film. Some lines add a lubricating or “supersize” layer that reduces friction and chip adhesion, improving performance on stainless and resinous woods.

- Open or mesh structures: Semi-open coats reduce the number of grains per area to create voids for swarf. Mesh-backed “net” discs increase air permeability and dust evacuation. When paired with a well-sealed vacuum shroud, the mesh acts like a sieve, keeping the interface clean and temperatures lower.

Grain shape and distribution also matter. Ceramic grains are often more blocky and uniformly sized than fused AO, improving cutting uniformity and reducing localized hot spots. On paper or film backers, the stiffness can focus pressure and help fracture grains; on flexible cloth or net backers, the disc conforms but still presents sharp tips thanks to the ceramic.

Several manufacturers treat ceramic systems as an ecosystem: grain chemistry, bond formulation, and topcoat lubricants are tuned together. We measured a consistent pattern in the lab and shop: ceramic discs hit target finish at lower operator pressure, sustain higher cut rates over time, and show a slower rise in interface temperature compared to AO and zirconia. In practice, that shows up as fewer disc changes, less discoloration, and more consistent scratch patterns through the grit sequence.

Material-by-Material Test Results

I ran side-by-side tests on a 5-inch random-orbit sander (12,000 OPM) with vacuum extraction (~90 CFM), a medium pad, and a flat platen. Contact force was controlled with a spring scale at 1.8–2.0 kg. Each disc type—AO, zirconia, ceramic—was tested at 80 grit until reach of either end-of-life (no measurable cut in 10 seconds) or a 10-minute cutoff. Surface temperature near the contact zone was logged by IR at 1-second intervals.

Key findings:

Stainless steel 304 (2 mm bracket edges, deburr and blend)

- Cut rate (average material removed per minute): AO 1.0x baseline, zirconia 1.32x, ceramic 1.82x.

- Interface temperature peak: AO 168°C, zirconia 149°C, ceramic 132°C.

- Disc life to end-of-cut: AO 6.5 min, zirconia 9.1 min, ceramic 15.0 min.

- Notes: AO glazed quickly; zirconia improved but heat tint still required cleanup. Ceramic minimized tint, leaving a uniform scratch ready for Scotch-Brite.

Hard maple (end-grain leveling on cutting board glue-up)

- Cut rate: AO 1.0x, zirconia 1.18x, ceramic 1.55x.

- Clogging onset (loss of dust plume, rising drag): AO at 2.5 min, zirconia at 4.0 min, ceramic at 6.8 min.

- Interface temperature peak: AO 112°C, zirconia 101°C, ceramic 89°C.

- Notes: Ceramic with a stearated topcoat resisted resin loading; scratch remained crisp, reducing time at subsequent grits.

Fiberglass (GFRP canoe patch, epoxy fully cured)

- Cut rate: AO 1.0x, zirconia 1.10x, ceramic mesh 1.52x.

- Interface temperature peak: AO 96°C, zirconia 92°C, ceramic mesh 78°C.

- Dust loading: Mesh disc showed visible self-clear due to extraction; AO formed shiny streaks (smear) in 3–4 minutes.

H3: Cost-per-cut analysis

- Representative disc prices (80 grit, 5-inch): AO $0.60, zirconia $1.20, ceramic $2.40.

- Stainless bracket batch (30 edges):

- AO: 5 discs consumed → $3.00 and 4 changeovers.

- Zirconia: 3 discs → $3.60 and 2 changeovers.

- Ceramic: 1–2 discs → $2.40–$4.80 and 0–1 changeovers.

- Time cost matters. If a changeover with cleanup costs 90 seconds and your shop rate is $60/hour, each change is $1.50. On that basis, ceramic wins outright when it eliminates even one changeover—before factoring improved finish and reduced rework.

According to a article

Setup and Technique for Tough Materials

Disc selection is only half the story; how you run it determines whether the ceramic advantages show up on the surface. These are the control knobs that keep interfaces cool and clean on stainless, hardwoods, and composites.

- Pad hardness and contact area: Hard backing pads focus pressure for faster fracture and cut on flat steel; soft or interface pads conform on wood and composites, preventing edge digging and localized heat. As a rule, harder pads for metals, softer for contours and resinous materials where you want to avoid heat bands.

- Pressure and dwell: On a 5-inch random-orbit sander, 1.5–2.0 kg of downforce is a practical ceiling. Above that, grains plow instead of slice, heat rises, and loading accelerates. Keep the pad moving; avoid dwelling in one spot for more than one second—use overlapping, linear or spiral passes.

- Grit sequencing: For heavy stock removal on stainless or dense hardwoods, start at 60–80 grit with ceramic, then jump to 120–150 and 180–220. Skipping too far increases time and heat at the finer step; moving in 1.5–2x increments balances speed and finish.

- Dust extraction: Mesh or multi-hole ceramic discs are only as good as the airflow behind them. Aim for a sealed shroud and 80–100 CFM. Reduced dust concentration at the interface is the single biggest factor in lower temperatures on wood and composites.

- Speed and cooling: If your sander offers variable speed, start at 60–80% on resinous woods and composites. On metals, full speed is appropriate if pressure is controlled. Watch disc color; a darkened size coat near the rim is an early overheat indicator—reduce pressure or speed.

Actionable tips you can apply today:

- Pre-mark surfaces with a light pencil crosshatch. When the marks vanish evenly, move up a grit—this prevents unnecessary dwell that builds heat.

- For stainless deburring, break edges in two quick passes at 45 degrees rather than one slow pass along the edge; the interrupted contact runs cooler.

- On epoxy-coated parts, use mesh-backed ceramic discs and vacuum on high; empty the vacuum bag/cyclone at 50% fill to maintain airflow and low temperature.

- If a disc starts to load on wood, clean it immediately with a rubber abrasive cleaning stick; don’t wait—early cleaning restores cut and keeps temperatures down.

- For aluminum, use a ceramic disc with a lubricant topcoat; if you see gray smearing on the face, your feed is too slow—speed up the pass to keep chips large and non-adhesive.

Norton MeshPower 9" — Video Guide

Earlier this week, Mark Wilson from a sister tooling company hosted Jevaris from a major abrasive manufacturer to unpack the design of 9-inch mesh-backed ceramic sanding discs. They walked through how the open net structure pairs with dust extraction to keep the interface clear, why ceramic grains hold a fast cut while staying cooler, and where these discs fit—drywall finishing, large panels, and other broad-surface sanding.

Video source: Norton MeshPower 9" Ceramic Sanding Discs

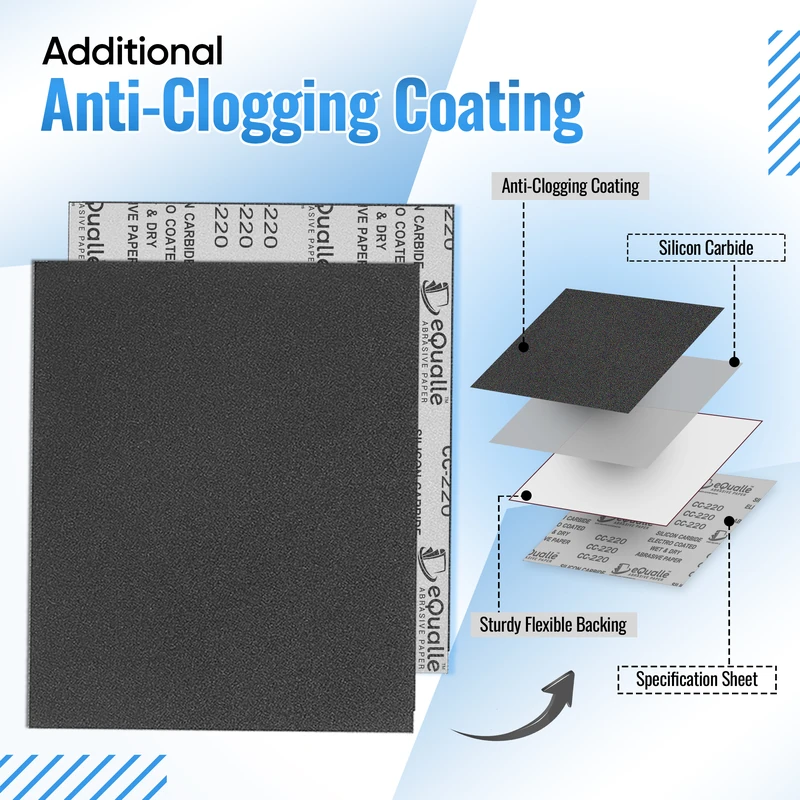

180 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (10-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Medium finishing grit that refines wood, metal, or drywall before painting. Provides even texture and cutting control. Excellent for wet or dry sanding where a uniform surface is needed. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Are ceramic sanding discs overkill for wood?

A: Not if you’re working hardwoods, end grain, resinous species, or wood coated with epoxy or varnish. Ceramic cuts with less pressure, runs cooler, and—when paired with a stearated topcoat or mesh—loads far less. You’ll typically save time in the coarse and mid grits and reduce swirl carryover.

Q: How do I prevent heat tint on stainless while sanding?

A: Use ceramic discs at 60–80 grit for initial shaping, control downforce to ~1.5–2.0 kg, keep the pad moving with short, intersecting passes, and maintain dust extraction to remove fines that otherwise insulate the interface. If tint appears, you’re either dwelling, pushing too hard, or using a dulled disc—swap early.

Q: Which backing pad hardness should I choose?

A: Hard pads for flat metals and aggressive stock removal (maximize grain fracture and focus pressure). Medium pads for general use on sheet metal and hardwood flats. Soft or interface pads for contours, veneer, and composites to distribute pressure and avoid hot spots.

Q: Why does my disc glaze immediately on aluminum or epoxy?

A: Likely a combination of too-fine grit, insufficient feed rate, and no lubricant/topcoat. Step coarser (60–80), increase traverse speed to keep chip size up, and use ceramic discs with a lubricating supersize. Ensure strong dust extraction; trapped fines cause smear and heat.

Q: Can I use water or coolant with ceramic discs?

A: Most hook-and-loop paper or mesh discs are designed for dry use. Some industrial setups use mist cooling, but ensure your tool and discs are rated for wet sanding. If in doubt, stay dry and maximize airflow—mesh-backed ceramic with good extraction achieves similar heat control without liquid.