Boat Sanding Grit Guide for Antifouling Prep

You feel it as soon as the travel lift sets your boat on the stands: that mix of relief and responsibility. The hull looks taller on land, the waterline a faint stain of the season gone by. There’s a quiet rhythm to the boatyard in the early hours—compressors breathe, gulls trade commentary, coffee cools beside a bucket of scrapers. You run your hand over the bottom paint and feel the story of boat sanding before you even begin: the hard, glossy ridges where the sander skipped, the chalky patches that might be underbound, the thin spots the sea worked harder than you realized. It’s tempting to rush the job and get straight to brushing on antifouling. But prep is where the next season is won. Choosing the right grit is the difference between a coat that stays put and one that blisters, powders, or peels when the boat is back in her element.

If you’re new to antifouling paint prep, grit numbers can feel counterintuitive—lower means rougher, higher means finer. And yet, the “right” grit is never one-size-fits-all. It depends on what’s already on the hull, what you want to achieve (stripping, fairing, or just scuffing), and what you’ll apply next. The good news: a thoughtful approach to grit selection saves time, materials, and elbow grease, while reducing dust and waste. This guide walks you through when to use 60 vs. 80 vs. 120, how to work a sander without gouging, and why a smooth-but-toothy surface is everything. We’ll keep it practical: specific grit roadmaps, tool choices, safety, environmental care, and finishing steps so your antifouling bonds cleanly and lasts.

Quick Summary: Choose grits to match your goal—60–80 for removal and fairing, 80–120 for scuff-sanding existing antifouling, and 120–180 for between-coat smoothing—then sand methodically with dust control and light pressure for a toothy, even profile that locks in new paint.

Antifouling prep, demystified

The goal of antifouling prep is not a mirror-smooth hull; it’s a controlled surface profile that the next coat can key into. Too coarse, and you’ll waste paint and create drag; too fine, and the new coating can’t grip. Most bottoms already have layers of old antifouling. Your first decision: remove or refresh.

- Refresh/scuff-sand: When the existing paint is sound—no widespread flaking, blisters, or soft spots—your job is to clean, dull the gloss, and create micro-scratches for mechanical adhesion. This is usually an 80–120 grit task.

- Partial removal/fairing: If there are ridges, runs, or transitions between paints, you’ll level them first. This calls for 60–80 grit in localized areas, then a blend-out with 100 grit.

- Full strip: When adhesion has failed, incompatible paints were used, or you’re switching systems, you’ll strip chemically or mechanically. Mechanical stripping often begins coarser (36–60 grit) but takes skill and care to avoid hull damage.

Surface cleanliness matters as much as the scratch pattern. Wash the hull to remove salt and slime; salt crystals are abrasive and can scar gelcoat. After drying, identify “failure” areas—flaking edges, chalking zones, or exposed substrate. Mark them with a wax pencil. Plan your passes: broad scuff sanding for the whole bottom, spot-fairing where needed, and careful attention at waterline, through-hulls, and strakes.

Dust control is more than a courtesy; it’s a health and environmental requirement in many yards. Opt for vacuum-extracted sanding setups and ground tarps. Finally, think ahead to the paint you’ll apply. Hard epoxies, ablatives, and copper-free formulas may each specify a target grit or prep method. Following that guidance ensures warranty coverage and performance.

Choosing grit for boat sanding and fairing

Let’s turn the chaos of grit numbers into a simple roadmap. Grit sets the size and shape of the scratches you put into the existing coating. Those micro-grooves increase surface area and give the new antifouling something to bite.

- 60–80 grit: Use for flattening ridges, sanding old drips and runs, knocking down heavy buildup, and fairing transitions. Keep your touch light—this grit can dig fast.

- 80–100 grit: The sweet spot for scuff-sanding sound antifouling paint. It dulls gloss uniformly and leaves a toothy surface without oversizing the scratches.

- 120 grit: Good for final passes on hard, dense coatings and for smoothing after localized fairing. Especially helpful if your next paint prefers a slightly finer profile.

- 150–180 grit: Typically for between-coat smoothing of primers or barrier coats, not for initial antifouling scuff. Too fine on a glossy bottom can reduce adhesion.

- 220+ grit: Rare under the waterline during prep for antifouling; risks polishing rather than preparing.

Actionable steps:

- Start with a test patch: Sand a one-square-foot area with 80 grit on a random orbital sander, vacuum attached. Wipe clean and inspect. If gloss remains, drop to 60–70 grit locally; if you get deep swirl marks, bump up to 100–120.

- Blend, don’t leap: If you must use 60–80 grit to flatten, follow with a quick pass of 100–120 over a wider halo so you don’t leave coarse “targets” that telegraph through paint.

- Crosshatch: Move the sander in overlapping passes at roughly 45° angles, then cross the pattern. This avoids low spots and ensures even tooth.

- Treat edges gently: Switch to a soft interface pad or hand-sand with a block at chines, strakes, and around through-hulls to avoid gouges.

Common mistake to avoid: using one coarse grit across the entire hull for speed. You’ll remove too much material, increase drag, and consume more paint. Let your goal dictate your grit.

Sander types, technique, and dust control

Tool choice affects the scratch pattern as much as the grit. For most boat bottoms, a 5" or 6" random orbital sander (ROS) with variable speed and a quality dust-extracting vacuum is the gold standard. The random orbit motion reduces swirl marks and helps you keep an even touch over curves.

Technique that works:

- Speed and pressure: Run your ROS at medium speed with very light hand pressure—just enough to keep the pad planted. Pressing hard slows the pad, clogs abrasive, and creates swirl scars. If the tool isn’t cutting, your grit is too fine or your disc is spent.

- Keep it moving: Work in zones you can finish without fatigue. Move at a steady 1–2 inches per second with 50% overlap. Pause only with the pad off the surface.

- Fresh discs, often: Change discs at the first sign of glazing. A dull disc generates heat, melts old paint, and produces sticky dust pancakes that scratch unpredictably.

- Interface pads: Use a 1/4" soft interface pad to sand around curves and prevent edge-cutting—especially important in the 60–80 grit range.

- Hand sanding: For tight spaces, scuppers, and trailing edges, a cork or foam block with the same grit keeps your scratch pattern consistent.

Dust and safety:

- HEPA vacuum: Connect your sander to a HEPA-rated extractor. This reduces airborne copper and biocide dust and keeps the surface cleaner for inspection.

- PPE: Wear a P100 respirator, eye protection, and gloves. Antifouling dust is not something your lungs or skin want to meet.

- Containment: Lay ground tarps and use skirts around stands. Many yards require this, and it makes cleanup faster.

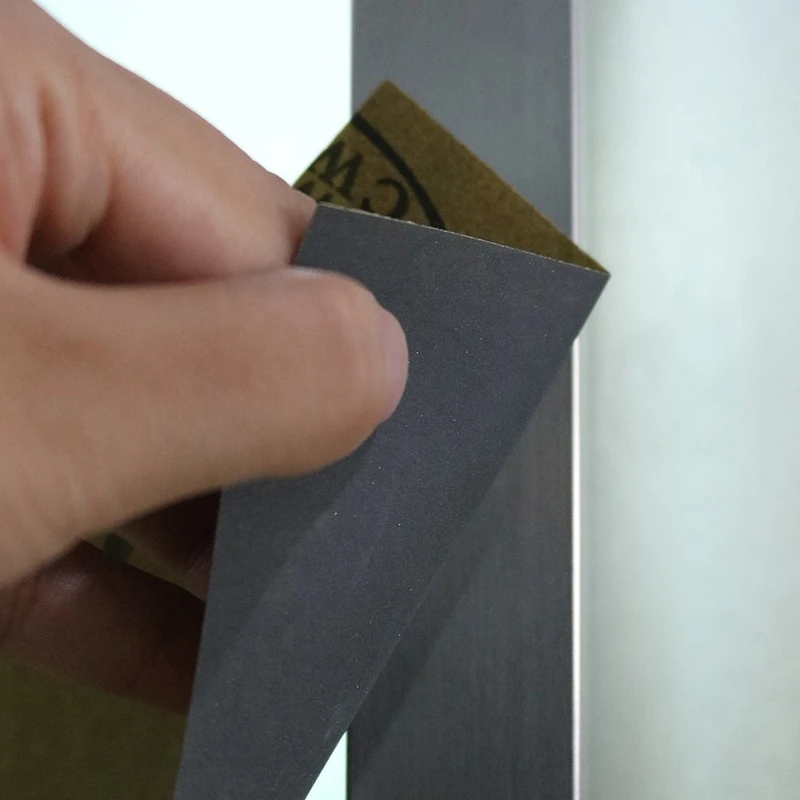

- Wet vs. dry: Some yards prefer wet sanding to keep dust down. If wet sanding, choose wet/dry paper in the 100–120 range, keep the surface rinsed, and be mindful of runoff containment.

According to a article

Pro tip: Mark each zone with painter’s tape and note the last grit used. You’ll maintain consistency across work sessions and reduce accidental over-sanding.

Grit roadmaps by hull material

Not all substrates behave the same. Gelcoat, aluminum, steel, and wood each need a slightly different approach to protect the structure while achieving the right tooth.

Fiberglass/gelcoat

- Scenario A: Sound existing antifouling you’ll refresh

- Clean thoroughly, then scuff with 80–100 grit ROS. Spot-fair ridges with 80 grit and blend with 120. Wipe with a compatible solvent or cleaner per paint specs.

- Scenario B: Thin or patchy antifouling

- Feather edges with 80 grit and blend with 100–120. If you expose gelcoat, avoid polishing it smooth—stop at 120 in those areas so primer or paint can grip.

- Scenario C: Stripping to gelcoat and re-priming

- Use chemical strippers designed for fiberglass or cautiously sand 60–80 to remove bulk paint, then 80–100 to fair. Avoid cutting into gelcoat. Follow with barrier coat per manufacturer.

Aluminum

- Avoid aggressive grits that create deep scratches susceptible to corrosion. Target 80–120 for scuffing and 100–150 for primer prep. Use aluminum-safe, copper-free antifouling. Vacuum thoroughly; no steel wool.

- Keep dissimilar metal dust away. Dedicated abrasives prevent contamination.

Steel

- You’ll often be addressing rust and coatings systems. Mechanical prep might start with 60–80 on heavy scale (or blasting by a pro), then 100–120 before primer. Maintain a clean, dry surface between steps—flash rust can appear quickly.

- Follow coating manufacturer’s required profile (often expressed as SSPC standards) if blasting.

Wood

- Gentle and even. Start at 100 for scuffing existing antifouling, rarely coarser than 80 unless fairing epoxy or fillers. Wood fibers fuzz if over-sanded; finish with 120 prior to primer or antifouling.

Composite/epoxy barrier coats

- Treat barrier coats with care. Typically 120–180 grit between coats per spec; for antifouling over barrier, many systems call for 80–120 scuff to ensure bond without compromising the barrier.

Three quick checks before painting:

- Wipe test: After sanding and vacuuming, wipe with a clean white rag. If you pick up lots of colored dust, clean again. Dust is a bond-breaker.

- Water break: Mist water on the surface; it should sheet evenly. Beading suggests contaminants—wash and lightly re-sand.

- Uniform dullness: Look for consistent matte finish and no glossy pits. Glossy specks are spots you missed.

When to prime, when to paint

Grit selection and primer decisions go hand-in-hand. Antifouling paint needs either a sound, compatible old coating or a suitable primer/barrier beneath it. Know when to stop at a scuff and when to add a primer tie-coat.

Prime first if:

- You’ve exposed bare gelcoat, aluminum, or steel in more than small spots.

- You’re switching between incompatible antifouling types (e.g., from a hard paint to some ablatives) and the new system calls for a tie-coat or sealer.

- You see widespread chalking—sand can’t fix chemically degraded surfaces.

- You’re building or renewing an epoxy barrier system for osmosis protection.

Skip primer if:

- The existing antifouling is intact, you’ve scuff-sanded uniformly with 80–100 grit, and your chosen paint lists the previous coating as compatible.

- Touch-up areas are small and feathered well; many antifoulings can bridge minor transitions over a properly sanded surface.

Grit-to-primer pairing:

- Bare fiberglass: 80–100 grit to promote epoxy primer adhesion.

- Epoxy primer to antifouling: 120 grit as a final pass, then apply within the primer’s overcoat window.

- Aluminum or steel: Follow the coating system’s specified profile; commonly 80–120 before an epoxy or zinc-rich primer.

Timing matters. Many primers have a recoat window where the next layer bonds chemically without extra sanding. If you miss it, a light 120–180 grit scuff restores adhesion. Keep a log on your hull of dates, temps, humidity, and products used—future you will thank present you.

Five actionable tips:

- Use a gray Scotch-Brite pad to scuff tight corners after sanding; it evens out scratch patterns.

- Store abrasives in a sealed bin. Humidity softens backing and clogs grit prematurely.

- Label your sander speed setting for each grit. Consistency reduces swirl marks.

- Keep two sanders set up with different grits for efficiency and to avoid constant disc swapping.

- Vacuum, then tack-cloth with a paint-system-approved wipe—no silicone or oily rags.

Minimizing drag without over-sanding

A fast, efficient bottom is about balance. Antifouling needs bite, but a forest of deep scratches increases friction. Here’s how to keep hydrodynamics in mind while you prep.

Focus on fair, not flawless. Longboard or block-sand filler and high spots with 60–80 grit only where needed. Immediately follow with 100–120 to reduce the scratch depth. The large-surface scuff should sit mainly in the 80–100 range. Reserve 120 for smoothing patches and between-coat work, not the whole hull.

Edges and appendages—keels, rudders, skegs—deserve special care. They’re drag multipliers if rough, and they often show more damage. Hand-sand these with a block to keep profiles crisp. On rudders, inspect for hairline cracks and water ingress; repairs come before sanding.

Mind your paint film build. Heavy coats fill scratches but add weight and texture. Two well-applied coats with even tip-off usually beat three sloppy ones. If you can feel scratch ridges after sanding, you probably went too coarse or pushed too hard. Back off and refine.

Performance check:

- After scuff-sanding, run a gloved hand across a few zones. You want uniform “tooth” without pronounced grooves.

- Sight along the hull in low-angle light. High and low patches pop; address them locally, not across the entire surface.

Finally, document what worked. Note the grits, tools, and time per section. Next season’s prep gets faster and more predictable when you repeat a proven scratch profile rather than reinventing it.

Bottom Job Paint — Video Guide

If you prefer to learn by watching, there’s a thorough how-to video that walks through removing old bottom paint, sanding methodically, and applying fresh antifouling on a sailboat. You’ll see an orbital sander in action, how to manage dust, and where a coarser grit is justified versus when to switch finer.

Video source: Bottom Job Paint Removal , Sanding and Painting Your Boat: How to Step by Step on a Sailboat, 2024

280 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (10-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Fine abrasive for leveling varnish or clear coats with precision. Creates a refined surface before high-gloss finishing. Performs reliably on wood, resin, or painted materials in wet or dry conditions. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What grit should I use to scuff existing antifouling?

A: For most sound antifouling paints, 80–100 grit with a random orbital sander creates ideal tooth. If the surface is very hard or glossy, finish with 120 in a light pass.

Q: Is hand sanding good enough, or do I need a power sander?

A: Hand sanding works for tight areas and small boats, but a vacuum-equipped ROS delivers faster, more uniform results with better dust control. Many yards prefer or require dust extraction.

Q: Do I need primer if I only sanded through to bare gelcoat in a few spots?

A: Yes—spot-prime any exposed substrate per the paint system’s instructions. Feather edges, prime those areas, then proceed with antifouling over the whole hull.

Q: Can I go finer than 180 grit before antifouling for a smoother finish?

A: Generally no. Too-fine sanding can polish the surface and reduce adhesion. Save 150–180 for between-coat primer smoothing and finish your antifouling prep at 80–120.

Q: How do I avoid swirl marks that show through the paint?

A: Use light pressure, keep the sander moving, run at medium speed, and step up one grit to refine after any 60–80 grit fairing. A soft interface pad also helps on curves and edges.