Glass Sanding: Keep Surfaces Wet to Control Heat

You know that afternoon light that hits your workshop just right—sawdust floating like golden confetti, the radio low, a mug ring etched into the bench? That’s where precision starts for me. I remember the first time I tried to smooth a chipped glass shelf salvaged from a vintage cabinet. I treated it like hardwood: dry paper, firm pressure, and a “let’s get this done” pace. Ten minutes in, the edge flashed white, my pad squealed, and the glass pinged with that terrifying, crystalline chatter. I learned fast: glass doesn’t forgive heat. It stores stress the way steel stores spring.

Glass sanding is different. The grit, the touch, the patience—they all matter—but the real game changer is water. Keeping surfaces wet transforms the job. You cut friction, dump heat, clear debris, and see exactly what you’re doing. Whether you’re easing a sharp edge on a glass tabletop, polishing an art panel, or cleaning up a cut on plate glass, water is the quiet partner that lets your abrasives do clean work without cooking the surface.

Maybe you’ve felt that tiny shock of heat rise through your fingertips while grinding a bottle edge or rounding an acrylic corner. Maybe you’ve watched a perfect pass end in a microchip because the surface went from cool to hot in seconds. Those moments aren’t about bad luck—they’re about temperature control. Keep it wet, and your sanding becomes repeatable, predictable, and professional. Today we’ll walk step by step through how to set up wet sanding for glass and other heat-sensitive materials, how to pick abrasives and speeds, how to manage slurry and power safely, and how to avoid the classic mistakes that cost time and parts. We’ll get practical: simple rigs that work, grit progressions that don’t bite back, and a feel for pressure that you can trust job after job.

Quick Summary: Wet sanding controls heat, prevents chipping, and delivers cleaner glass edges—use water flow, light pressure, and proper grits to build a flawless finish safely.

Why water beats heat in the workshop

Friction is heat, and heat is the enemy of precision on glass. When abrasive meets silica, the cut is microscopic and constant, and any heat you don’t pull away accumulates in the top fraction of a millimeter. That’s where stress builds and edges fail. Water interrupts that cycle. It lubricates the interface, carries away swarf, and acts as a thermal sink so your abrasive cuts instead of smears.

The result is immediate: quieter passes, a darker, clearer scratch pattern, and fewer mystery chips appearing two inches after your stroke ends. Wetting lets your grit do the work it was designed to do. It also keeps your abrasive cool, extending pad life and reducing loading. On glass and stone, silicon carbide and diamond media are your best friends; both thrive with water. Aluminum oxide will work in a pinch, but it dulls quicker on glass and tends to glaze if you run it dry.

There’s a safety layer too. Wet sanding lowers airborne dust—which is crucial when you’re dealing with respirable silica. That doesn’t mean you can ditch PPE; keep a P100 respirator handy for cleanup and a face shield when edges are exposed. Gloves with good tactile feel help, and I’m fond of a rubberized apron; it keeps slurry off your clothes and puts your mind on the work.

Use water smartly around electricity. Keep cords dry and elevated, plug tools into a GFCI-protected circuit, and prefer double-insulated, low-voltage equipment where you can. For hand work, a gravity-fed squeeze bottle or a small drip line is enough. For benchtop machines, a shallow tray and a controlled feed prevent splatter. The goal is consistent, modest flow—not a flood—so the surface stays wet, cool, and readable without running a river across your shop floor.

Pro moves for glass sanding and cooling

This is where the craft shows. A clean, safe, chip-free glass edge is built by sequencing grits, managing pressure, and feeding water to keep temperatures tame.

Step-by-step for a typical edge repair:

- Break the edge. Start with 220–320 grit silicon carbide or a fine diamond pad. Round off the knife-edge with three light passes, water running. Keep the pad flat; rocking digs.

- Establish the scratch pattern. Move to 400–600 grit. Sand in a different direction to track progress. You’re done when the coarser scratches are gone and the edge feels uniform—no hot spots.

- Refine and pre-polish. Hit 800–1200 grit with steady water flow. Pressure should be just enough to keep the pad in contact—think two fingers, not your whole hand.

- Polish optional. If you want clarity, use a dedicated felt or foam pad with cerium oxide slurry. Light, slow passes keep temperature out of the red zone.

Practical tips:

- Keep it wet, not wild: a steady bead or mist is better than blasting. You should always see a milky slurry trail; that’s cutting debris leaving the work.

- Ride the pad, don’t lean. If you feel heat through gloves, you’re pushing too hard or running too dry.

- Reset between grits. Rinse the glass and pad before switching. Carryover grit is a scratch factory.

- Use the whole pad face. Shorten dwell time on corners; they build heat fastest.

For edges on tempered glass, do not attempt heavy removal—the residual stresses can release unexpectedly. For annealed or laminated glass, confirm the laminate’s tolerance for water exposure at the edge. Always support the work off the bench with a rubber mat so you can overhang the edge safely without flex.

Dialing in grits, pads, and pressure

Grit selection is your roadmap. For scratches you can feel with a fingernail, begin around 220–320. For microchips and saw marks, 400–600 starts cleaner. Past 800, you’re refining, not correcting—stay longer at the coarser stage to save time later. With silicon carbide sheets, change often; if the sheet looks polished, it is. Diamond pads last longer but still benefit from water and light dressing on a sacrificial tile to keep them cutting true.

Pad hardness matters. A soft foam-backed diamond pad will conform to curves and spread pressure, keeping heat down. A hard backing cuts fast but concentrates energy—use only when you need to flatten or re-square an edge. Maintain a medium speed; on a variable-speed tool, think 2–3 out of 6. Too slow, and you’ll stutter and grab. Too fast, and heat spikes between water beads.

For flat faces, a platen with a thin water film gives the most even finish. Rotate the work often and alternate stroke directions with each grit change so you can visually track when the previous scratches are fully replaced. If you’re chasing perfection, finish each stage with a few feather-light passes—pressure drops heat dramatically and refines the scratch edges.

Wet methods aren’t just safer—they’re documented to reduce thermal shock. According to a article, wet grinding helps prevent excessive heat buildup and lowers the risk of breakage. That’s exactly what you feel in your hands when the pass stays cool and the edge stays calm.

Rule of thumb for pressure: if water isn’t streaming off the edge and you can hear the abrasives singing rather than squealing, you’re in the zone. If you see steam, stop immediately—wipe, cool, and resume with more water and less force.

Water management that actually works

Good water control keeps you efficient and dry. You don’t need a factory setup—just a steady supply, containment, and safe power.

Simple rigs:

- Squeeze bottle and tray: Place your work on a rubber mat inside a shallow plastic bin. Drip from a condiment bottle as you sand. The bin catches slurry; the mat keeps the glass stable.

- Gravity drip: Hang a 1–2 liter reservoir (even an IV-style plant watering bag works) and run vinyl tubing to a pinch valve clipped near your hand. Dial the drip to a slow bead across the work line.

- Recirculating loop: For longer sessions, set a small submersible aquarium pump in a bucket with clean water. Pump to your work via tubing, and return slurry to a separate waste bucket so you’re not grinding with grit-laden water.

Keep power safely away. Elevate cords, use GFCI outlets, and institute a “dry hands on plug” rule. If you’re using a corded sander, consider a splash guard or a simple corrugated plastic shield between the tool body and the wet area. Battery tools minimize cord risk but still require careful handling; don’t drip water onto vents.

Slurry disposal matters. Let the bucket sit overnight; sediment will settle. Decant the clear water up top for reuse or disposal per local rules, and collect the sludge in a sealable container. Never pour glass fines down a sink—they’ll set up like concrete in traps. Wipe tools and pads with a damp rag before they dry; dried slurry is abrasive and shortens tool life.

Temperature checks are small but smart. Touch the edge with the back of your finger every few passes—if it’s warmer than your skin, add flow or pause. On long runs, rotate parts in and out so each has time to cool naturally. A cheap infrared thermometer makes you honest: keep surfaces below 90–95°F for stress-free work.

Finishing, inspection, and fixing mistakes

Your finish is only as good as your inspection. Raking light is the truth-teller—place a bright lamp low to the surface and tilt the glass until scratches pop. Use directional sanding with each grit so you can see patterns cross and replace. When the previous direction disappears, move on.

If you’re going for a frosted satin edge, stop at 600–800. For a glossy edge, refine to 1200 or 1500 before switching to polish. Mix cerium oxide to a thin cream and apply lightly with a felt pad. Keep the polish wet—cerium generates heat quickly. Clean pads frequently; loaded polish burns.

Common fixes:

- White haze or bloom: That’s heat. Back up one grit, increase water, and lower speed. Finish with feather-light passes.

- Microchips along the edge: Your pressure concentrated at corners. Slightly chamfer both arrises before refining the flat. Use a softer backing pad to spread force.

- Tiger striping (alternating dull and bright streaks): Uneven contact. Flatten your backing, refresh your pad, and ensure the work is fully supported.

Edge safety is part of the finish. A tiny break—just a pass or two at 400–600—at both arrises reduces chipping in use and makes handling safer. For laminated glass, keep breaks minimal to protect the interlayer from water ingress; finish with isopropyl wipe-down and dry thoroughly.

Don’t neglect cleanup. Rinse glass with clean water, then wipe with microfiber to avoid re-scratching. Dry tools and bins, then lightly oil steel surfaces on your machines. Label used pads with their grit and “glass” so you don’t cross-contaminate with wood or metal—stray steel on a glass pad can scratch deep and unpredictably.

Beginner Sanding Mistakes — Video Guide

If you’re new to sanding—or you’ve learned the hard way that “just push harder” isn’t a plan—this video breaks down the fundamentals. It reframes sanding as a skill: managing pressure, reading the scratch pattern, and letting the abrasive do the work without forcing it. While the focus is on woodworking, the principles map directly to wet sanding on glass—especially the parts about staying patient and keeping consistent motion.

Video source: Beginner Sanding Mistakes | How to Sand

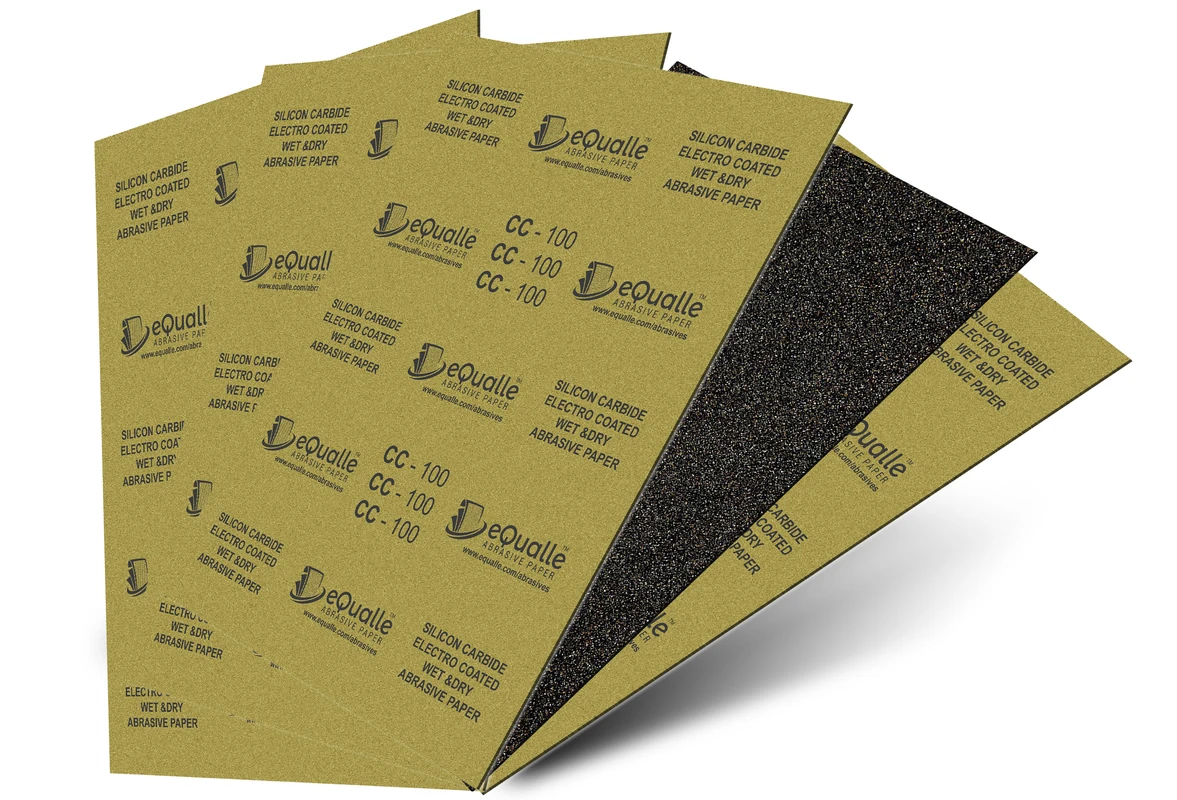

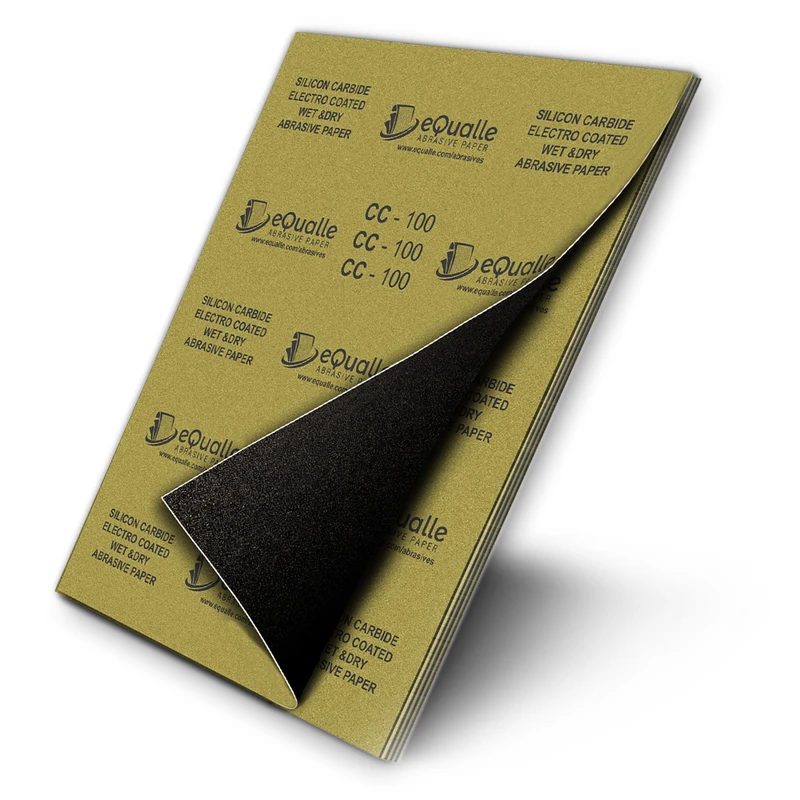

280 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (100-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Fine finishing grit for delicate work—ideal for flattening varnish layers and creating a pre-polish smoothness on wood or resin. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Can I dry sand glass if I’m careful?

A: You can, but it’s risky. Dry sanding builds heat fast, raises chip risk, and creates hazardous silica dust. Wet methods cut cooler, cleaner, and safer—use water.

Q: What grits should I use for a chipped glass edge?

A: Start around 220–320 to break the edge, move to 400–600 to remove damage, then 800–1200 to refine. For a glossy edge, finish with a cerium oxide polish.

Q: How much water is enough during glass sanding?

A: Aim for a steady bead that keeps a milky slurry present. The surface should stay visibly wet without pooling. If you feel warmth, increase flow or reduce pressure.

Q: Is diamond better than silicon carbide on glass?

A: Diamond cuts cooler and lasts longer, especially on hard glass. Silicon carbide is affordable and effective but wears quicker. Both require water for best results.

Q: How do I stop corners from chipping?

A: Lightly chamfer both arrises first, use a soft backing pad, keep pressure even, and shorten dwell time at the ends of your stroke. Always keep the edge wet and supported.