Grit Progression for Bare Wood: A Practical Guide

The shop is quiet except for the low thrum of the dust collector warming up. A mug of coffee cools on the bench while you run your fingertips across a fresh board—straight from the planer, faint ridges under the grain. Last time, you started too fine and paid for it with stubborn tear-out lines that only became visible after stain. This time you want a better plan. You want a clear grit progression that fits the wood, the project, and the finish you’ve chosen.

It’s not just about sanding more; it’s about sanding smarter. Grit progression is how you move from coarse to fine abrasives in controlled steps, each one removing the scratches of the last while preparing the surface for stain, paint, or a natural finish. Do it right and you’ll avoid swirl marks, blotchy color, and that dreaded “plastic” look. Do it wrong and you’ll chase defects for hours, or worse, lock them under a finish you can’t easily fix.

There’s craft in this. The wood species, the way your boards were milled, even the humidity in your shop: they all influence where to start and where to stop. Pine face frames don’t want the same sequence as a white oak tabletop. Water-based finishes raise grain, oil finishes reward extra refinement, and paint needs “tooth.” The steps don’t have to be complicated, but they do need to be intentional.

Let’s slow down and walk it through—what to check before you pick up paper, how to choose starting grit, when to stop, and how to handle edges, end grain, and tricky spots. Along the way, you’ll pick up practical checkpoints so you know when you can move on without second-guessing. By the end, you’ll have a repeatable, confident routine for bare wood that actually saves time and elevates your results.

Quick Summary: A smart grit progression removes defects efficiently, matches the project and finish, and ends at the coarsest grit that achieves a flawless surface—typically 180–220 for most bare wood.

Start smart: assess the wood

Before choosing a single sheet, read the board. The right starting grit depends on how the surface was prepared, the species, and the defects you see and feel.

- Milling marks and tear-out: If you see planer ridges or shallow tear-out, start at 80 or 100. If a jointer left faint scallops, 100–120 is typical. For sawn faces or reclaimed lumber, 60–80.

- Species and density: Softwoods (pine, fir) bruise easily and can burnish early; start moderately coarse (100–120) and avoid over-sanding. Dense hardwoods (maple, white oak) often need 80–100 to fully remove tool marks.

- Flatness and glue lines: High spots and dried squeeze-out require a coarse grit to level quickly. Don’t torture 150 grit trying to erase a ridge that 80 grit will fix in a few passes.

Test with your senses. View under raking light (a flashlight at a low angle) to highlight scratches and defects. Lightly “pencil-squiggle” the surface before each pass; when the squiggles disappear evenly, you’ve hit every area. Touch matters too: close your eyes and run your fingers along the grain to feel remaining ridges that your eyes may miss.

Pick a sensible starting point:

- Freshly planed hardwood with light ridges: 100

- Pine face frames from a good planer: 120

- Tabletop with visible tear-out: 80–100

- Veneer or thin stock: 150 (be cautious and use a firm backer)

Resist starting too fine. If 120 can’t remove a planer ridge in 30–45 seconds on a 5" random orbit sander, drop to 100 or 80. The first grit does the heavy lifting; after that, you’re refining the scratch pattern. Keep the sander flat, move at a measured pace (about 1–2 inches per second), and let the abrasive cut—no added pressure.

Dialing in grit progression by project type

Here are reliable, project-based sequences that prioritize efficiency and finish quality. Use them as starting points and adapt to your wood and tools.

- Tabletop (hardwood, clear finish): 100 → 120 → 150 → 180 → hand-sand with the grain at 180. For ultra-smooth oil finishes, add 220 after raising the grain (mist with water, dry, then sand).

- Painted cabinets and trim: 100 → 150. Stop at 150 for better mechanical tooth. After primer, scuff sand 220 before topcoat.

- Stained pine face frames: 120 → 150 → 180. Stop at 180 to help color penetrate evenly and reduce blotching. Consider a pre-stain conditioner if needed.

- Cutting boards (end grain): 80 → 120 → 150 → 180 → 220. End grain loves to drink finish; stop at 220 for clean fibers without burnishing.

- Turned bowls and spindles: 80 → 120 → 150 → 180 → 220, with the lathe slowed down for finer grits to minimize heat.

As a rule of thumb, avoid giant jumps. A good “ratio” is to keep each jump around 50–70% higher than the previous grit (e.g., 120 to 180 is 50% higher). Big leaps like 80 to 220 can leave hidden scratches that reappear after stain or finish.

When to stop:

- Natural/clear finishes: 180–220. Going to 320 on dense woods can burnish the surface, reducing finish adhesion and causing blotchy stain.

- Stain: 150–180 on softwoods; 180–220 on hardwoods. Maple is especially sensitive: stop at 180 and consider a dye or toner to even color.

- Outdoor projects: 120–150. A slightly rougher surface improves finish grip and is forgiving in real-world wear.

Watch edges and end grain. Edge profiles are easy to over-sand—use a soft pad and keep it moving. For end grain, sand one or two grits higher than the face (e.g., if faces end at 180, take end grain to 220) to equalize absorption and color.

Between grits: technique, tools, and touch

Grit progression isn’t just the numbers—it’s the method. The way you move from one grit to the next determines whether you’re actually removing the previous scratches or just polishing them in place.

- Clean between steps: Vacuum dust from the surface, pad, and paper. Dust trapped under the pad acts like rogue coarse grit, creating fresh swirls.

- Mark your work: Light pencil squiggles reveal missed areas, especially on large panels and near edges.

- Slow down: Keep the sander flat and move steadily. On a random orbit, “hovering” too long while the pad isn’t spinning freely can cause pigtails.

- Pair abrasives to material: Aluminum oxide is an all-rounder. Ceramic or zirconia cuts cooler and lasts longer on hardwoods. Film-backed discs resist loading and help create consistent scratch patterns.

- Use the right pad: A firm pad levels quickly at coarse grits; a soft interface pad conforms on profiles at finer grits.

Hand-sand with the grain for the final pass at the grit you plan to stop. This aligns micro-scratches with the wood fibers, making them disappear under finish. Do not skip this on tabletops and show faces.

Raise the grain before waterborne finishes. Mist the surface, let fibers stand up, then sand lightly at your final grit (often 180–220). This prevents the first coat from feeling rough.

If you struggle to know when a grit is “done,” set simple checks: can you no longer see the previous grit’s pattern under raking light? Did pencil marks vanish evenly? Does a quick wipe with mineral spirits reveal uniform sheen with no cross-grain scratches?

A useful sanity check: many experienced woodworkers stop bare wood sanding around 180 for natural finishes, especially on softwoods. According to a article—that aligns with wide shop practice and avoids over-burnishing.

Prepping for stain, paint, or clear coat

Your finishing plan should steer the last two grits. Each finish type benefits from a slightly different endpoint and prep routine.

Stain

- Softwoods (pine, fir, spruce): Stop at 150–180. Sanding too fine can seal earlywood and cause blotchy absorption. Consider a washcoat or pre-stain conditioner for even uptake.

- Hardwoods (oak, walnut, cherry): 180–220. Cherry can get blotchy; testing on offcuts is essential. For maple, dye first or use a toner rather than pushing grit too high.

- Technique: After final sanding, vacuum thoroughly and wipe with a water-dampened cloth to raise grain. Once dry, lightly sand at the same final grit to knock down raised fibers.

Paint

- Bare wood: 120–150 before primer gives enough tooth. Spot-sand repairs at 100 to flatten, then blend to 150.

- After primer: Scuff sand at 220 to smooth nibs and improve adhesion of the top coat.

- Edges: Prime early and avoid over-sanding edges, which can quickly cut through and create adhesion weak spots.

Clear coat (oil, shellac, lacquer, waterborne)

- Oil and oil/varnish blends: Stop at 180–220. Oils highlight the grain; excessively fine sanding can reduce depth.

- Shellac/lacquer: 180–220 on bare wood; level coats between applications with 320–400 once cured as recommended by the manufacturer.

- Waterborne poly: Raise the grain, then finish at 180–220. Waterbornes can feel extra rough after the first coat; plan on a light 320 scuff between coats.

Always test on the same species, from the same batch, milled the same way, with your intended finish. A 3" x 10" cutoff is cheap insurance. Wipe with mineral spirits to preview how scratches will telegraph and note whether end grain needs an extra step.

Troubleshooting and pro-level tips

Even with a great sequence, the details matter. Use these targeted fixes and refinements.

Common problems and fixes

- Persistent swirl marks: Switch to fresh discs and check pad rotation; overloading stops the orbit. Slow your pass and hand-sand with the grain at the last grit.

- Blotchy stain: Back up one grit (e.g., 180 to 150) on softwoods, or apply a washcoat/conditioner. For maple, consider dye-plus-toner rather than pushing grit finer.

- Shiny, “plastic” look under clear finishes: You may have burnished the surface. Back up to 180, hand-sand with a block, and reapply finish.

- Raised grain after waterborne finish: Pre-raise with a light mist before finishing. After the first coat dries, scuff with 320–400 and recoat.

Pro-level practices

- Use a card scraper before sanding. It removes tear-out without compressing fibers, allowing you to start at a finer grit (e.g., 120 instead of 80).

- Map your surface. Pencil squiggles every pass, front and back. It’s the simplest way to hit everything evenly—especially on tabletops.

- Calibrate your “stop point.” On an offcut, sand half to 180 and half to 220, then apply your finish. Choose the side that looks better, not just smoother.

- Control heat. High speed and pressure glaze resinous woods and earlywood. Let the abrasive cut; if it feels hot to the touch, you’re pushing too hard.

- Keep abrasives clean. Use a crepe cleaning block on loaded belts and discs. Packed grit smears resin and creates new scratches.

Actionable tips you can apply today

- Standardize three core sequences on a shop card: “Natural/clear: 100–150–180; Stain: 120–150–180; Paint: 120–150.” Tape it near your sander.

- Keep two pads: firm for 80–120, soft/interface for 150+. Label them. This alone reduces swirls and over-rounding.

- Always end with a hand-sand along the grain at your final grit. Two minutes per panel can erase visible orbit patterns.

- Use raking light and pencil marks every grit. If you can’t see the previous scratch pattern, you’re ready to move on.

- Water-pop before waterborne finishes, then finish-sand at the same grit. You’ll avoid the rough first coat surprise.

Step By Step — Video Guide

A recent step-by-step video on sharpening kitchen knives walks through abrasive progression as a universal skill: start coarse to set the geometry, then refine through finer grits to erase the previous scratches. The presenter uses humor and shout-outs to supporters while methodically proving why each step matters.

Video source: Step By Step Grit Progression Kitchen Knife Sharpening

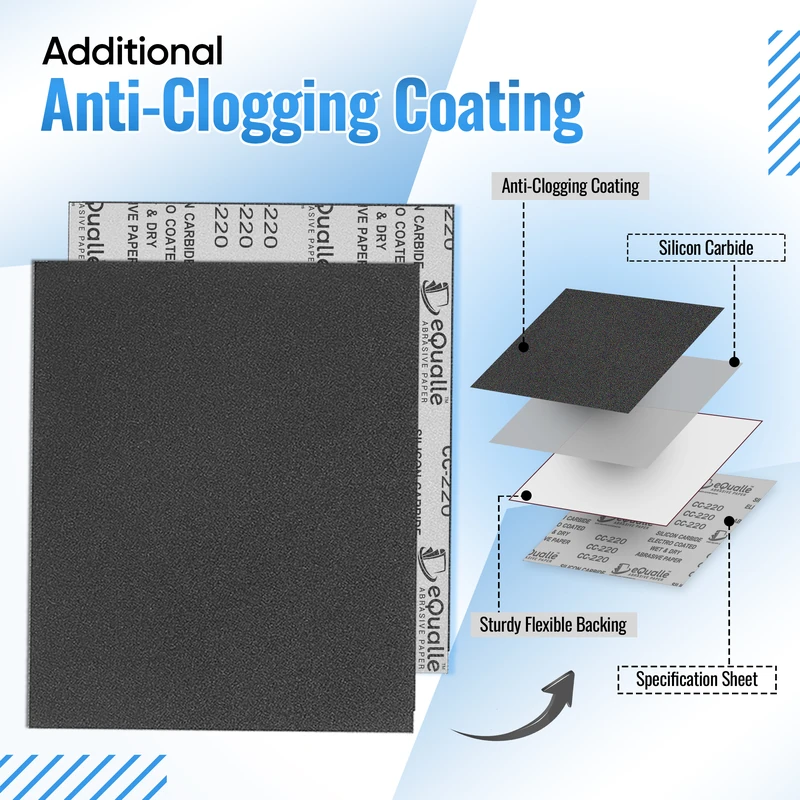

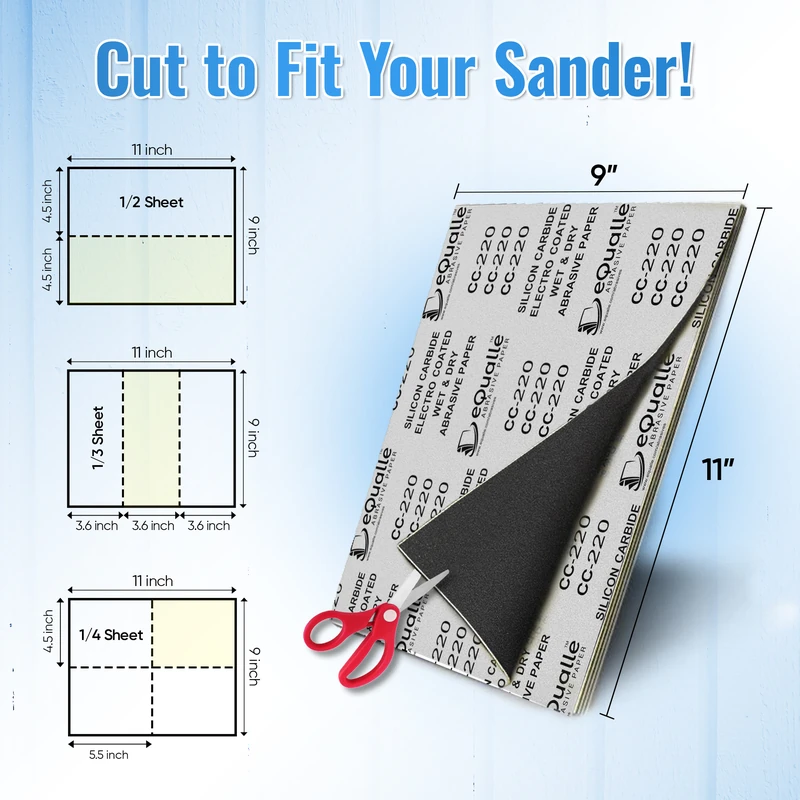

120 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (50-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Refines surfaces after coarse sanding by removing scratches from lower grits. Consistent performance on wood, drywall, and metal. Ideal for wet or dry finishing before applying primer or stain. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What grit should I start with on planed maple?

A: If the planer left faint ridges, start at 100. If you see tear-out, drop to 80. After the first pass erases milling marks, continue 120 → 150 → 180, and hand-sand with the grain at 180 or 220 depending on your finish.

Q: Is 220 too fine before stain?

A: Often yes on softwoods, where 150–180 gives more even color. On hardwoods, 180–220 is safe. Test on an offcut; if the color looks weak or blotchy, back up one grit or use a conditioner/dye approach.

Q: Can I skip from 80 to 180 to save time?

A: It backfires. Big jumps leave deep 80-grit scratches that reappear under finish. Keep jumps moderate—80 → 120 → 150 → 180 is efficient and ensures each step fully removes the prior scratches.

Q: How do I avoid swirl marks with a random orbit sander?

A: Keep the pad flat, use light pressure, clean dust between grits, and make steady passes. Use a firm pad for coarse grits and a soft interface for finer grits, then finish with a hand-sand along the grain.