Block Sanding Techniques for Dead-Flat Panels

The first time you notice the wave is rarely under shop fluorescents. It’s usually on a quiet evening, when the sun sits low and your freshly primed quarter panel mirrors a rippling skyline instead of a straight horizon. You run a hand over the surface—smooth, no pinholes, no obvious highs—yet the reflection trembles as if it remembers every hammer blow. That’s the moment every builder meets the truth: paint doesn’t hide shape. Only block sanding, done methodically with the right abrasives, pressure, and board geometry, can translate good bodywork into panels that read as laser-straight in unforgiving light.

The physics are simple but ruthless. Fillers and high-build primers add thickness; they don’t add flatness. Any low spot lets light bend and telegraph unevenness, while highs sand off instantly and return as shiny islands. The board is your straightedge-in-motion, a traveling datum that averages micro-peaks and shears off long-wave distortions. The goal isn’t just “smooth to the touch,” it’s uniform shape across the entire panel length. That distinction—shape over smooth—is what separates a driver-level refinish from a show-grade finish.

In this article, we’ll engineer a repeatable workflow for straightening wavy doors, hoods, and quarters. We’ll trade “feel” for measurable technique: stroke angles, grit progression, block stiffness, and guide-coat auditing that tells the truth on every pass. We’ll discuss how abrasive performance changes with load, how board length determines the wavelengths you can correct, and how to avoid rounding edges and print-through. Above all, we’ll make block sanding efficient—because the right process turns hours of guesswork into minutes of decisive shaping.

Quick Summary: Use long, flat blocks, coarse-to-fine abrasives, and guide coats in cross-hatched passes to remove long-wave distortion and achieve true, paint-ready flatness.

Why Panels Go Wavy

Waviness is shape error, not surface roughness. It comes from three main sources: metal distortion, filler thickness variation, and primer build inconsistency. Each produces different wavelengths of error:

- Long-wave distortion (8–36 inches): panel stretching from heat or over-hammering, often visible on doors and quarters.

- Mid-wave distortion (3–8 inches): uneven filler application, transition ridges, or block flex.

- Short-wave chatter (1–3 inches): aggressive DA patterns, interface pad ripple, or overly soft blocks.

Understanding wavelengths guides your tool choice. A board can only “span” and average defects longer than its contact patch. A 16-inch rigid longboard corrects 8–12 inch waves; a 24–30 inch board can iron out doors and hoods where reflections travel across feet of panel. Conversely, a 6–8 inch hand block is for local clean-up, not primary straightening.

Thermal and structural factors matter too. MIG-welded patches shrink; grinding concentrates heat; even panel adhesive can introduce stiffness gradients that read as low spots nearby. Filler shrinkage changes the surface weeks after application if catalyzation ratios or temperature were off. High-build primers can print the substrate’s character, especially if the underlying panel wasn’t uniformly blocked before priming.

Diagnosis precedes correction. Use raking light and a dry guide coat to map highs (shiny through-cuts), lows (persisting guide color), and plane transitions. Check with a 24–36 inch straightedge and light behind it to locate gaps. Pencil the panel into 6–8 inch grids; it helps correlate what you feel with what you see in the guide coat. If the metal is oil-canned or loose, no sanding sequence can lock it flat—address tension first with mechanical shrinking or controlled heat.

Block sanding strategy for true flatness

Block sanding is controlled averaging. Your board length, stiffness, and stroke angle define what wavelengths you eliminate and which you accidentally chase. Two rules keep you honest: always use the longest, flattest board you can control, and cross-roll your strokes in opposing diagonals.

- Stroke geometry: Work at 35–45° to the panel’s long axis, switching diagonals each pass. This cross-hatch approach prevents scalloping and reveals bias in your hand pressure. Keep stroke length long—18–24 inches where space permits—to let the board “read” shape beyond local defects.

- Pressure management: Apply roughly 1–2 psi of uniform pressure. If you see finger marks or striping in the guide coat, you’re gripping too hard or letting the board hinge at your wrists. Use an open palm and drive with shoulders, not fingers.

- Board stiffness: Start with a rigid, dead-flat longboard (16–24 inches) against straight or gently crowned areas. Move to a slightly flexible board when you must follow shallow crown radius (think outer door skins). Flex is a last resort; it should conform to shape, never create it.

- Path discipline: Keep full-panel passes. Don’t “spot fix” lows; that only deepens them. Let the board knock down highs around the low until it disappears in the next grit stage.

As a baseline sequence over high-build primer, start at P120 or P150 on a rigid board with dry guide coat. Once you have uniform guide removal and no shiny break-throughs on highs, recoat guide and move to P180–P220. Maintain the cross-hatch. The final pre-sealer pass (P320–P400) is for unifying scratch pattern, not correcting shape. Shape work ends by P220; anything finer only polishes your errors.

Precision cues matter: the board should “float” with a consistent hiss from abrasive cutting. Change paper the instant the sound dulls; a loaded sheet slides and rounds edges. Keep the board overlapping panel edges but protect adjacent radii with masking tape to avoid flat-spotting.

Abrasive selection and board geometry

Abrasive performance is your second straightedge. Ceramic-alumina and premium aluminum oxide sheets cut cooler and maintain grain sharpness longer than budget paper—critical when you’re removing millimeter-scale highs over large areas. For primer and filler, use open-coat, stearated abrasives to resist loading; for bare metal, prefer non-stearated sheets to avoid paint adhesion risks and to maintain consistent scratch depth.

- Grit progression: P120–P150 (shape), P180–P220 (refine), P320–P400 (pre-sealer). Skipping grits saves minutes but costs hours fixing embedded deep scratches that telegraph after color.

- PSA vs. hook-and-loop: PSA on rigid boards keeps a perfectly flat interface with zero nap; hook-and-loop can introduce micro-cushioning that softens the cut. Use PSA for shape-critical stages and switch to hook-and-loop only if your board design requires it.

- Interface pads: Avoid foam interfaces during shape work. Any compressible layer rounds, not levels. Reserve thin interface pads (2–3 mm) for later scratch refinement on gentle crowns, never for long-wave correction.

Board geometry governs the “averaging span.” Keep a stable of boards:

- 24–30 inch rigid longboard for doors, quarters, and hoods.

- 16–18 inch semi-rigid board for moderate crowns.

- 8–11 inch hard block for local transitions and jamb areas.

- Narrow beam blocks (1–1.5 inch width) for sail panels and wheel arch flats where a wide board bridges into curves.

Custom boards help on unique panels: glue PSA to milled aluminum or composite beams with proven flatness, or use laser-cut acrylic to ensure straightness. Check every board with a machinist’s straightedge; a bowed block teaches you the wrong lesson.

According to a article, long boards are non-negotiable for large, flat classics—short blocks simply ride the waves. That advice scales to modern panels: the longer the reflection, the longer your board should be.

Guides, glazes, and error-proof workflows

Guide coats turn invisible shape errors into obvious maps. Powder guide coats are dry, mess-free, and reapply in seconds; aerosol guides work but can load paper sooner. Apply guide coat after every primer build and between grit changes. Your rule: never sand without guide.

A reliable workflow:

- Rough-level filler with a 16–24 inch board and P80–P120. Stop when the guide shows uniform, faint traces in lows; don’t chase the last speck.

- Spray or roll two medium-wet coats of high-build 2K urethane primer; allow full cure per technical data sheet and temperature. Avoid premature sanding; undercured primer gums and rounds edges.

- Reapply guide and block at P120–P150 in cross-hatch passes until the surface reads uniformly flat with no persistent lows.

- Spot skim with glazing putty (polyester finishing glaze) only after the P150 stage, not before. Feather with P180 and re-prime small areas as needed rather than overworking adjacent flats.

- Finalize at P220, then P320–P400 to set a uniform scratch for sealer.

Field-proven tips that save time and shape:

- Work dry during shape stages. Wet sanding disguises loading and mutes guide visibility, prolonging errors.

- Use fresh, sharp paper. Rotate to a fresh third of the sheet as soon as the cut rate drops; dull grains skid and compress.

- Pencil critical lines and gaps (door-to-quarter, hood-to-fender). Sand toward the pencil, not across it, to keep panel breaks crisp.

- Tape off body lines and tight radii with 3–4 layers during coarse stages. Remove for final grit to restore a clean, crisp edge.

- Vacuum the panel every few passes. Dust accumulation under the board acts like rolling bearings and cancels your averaging effect.

Glazing putty is a scalpel, not a trowel. Apply paper-thin layers to fill micro-porosity and shallow lows (<0.3 mm). If you’re tempted to load it on, your panel needs another round of longboarding instead. A good glaze session is followed by a quick P180 block, a light prime for isolation, and an immediate return to P220 with guide.

Dust extraction, edges, and micro-contours

Dust isn’t just a housekeeping issue—it changes friction, heats the surface, and loads abrasives. Dustless longboards connected to a variable vacuum maintain a constant cut rate and reduce clogging by an order of magnitude. If you don’t have vacuum-capable blocks, at least use a brush and compressed air after each 5–10 strokes, keeping the nozzle at a shallow angle to avoid embedding dust.

Edges and body lines are where straight panels go to die. A longboard will happily flatten a body line if you let it. Protect these with tape stacks during P80–P150 work and train yourself to “walk off” an edge: finish each stroke by lifting the trailing edge of the block to reduce pressure as you cross a line. When refining, switch to a narrow, hard block and sand parallel to the line to preserve its radius and sharpness.

Micro-contours—like the subtle crown near a beltline or the slight dish at the top of a door skin—require selective compliance, not soft foam. Use a thin, semi-rigid board that you can preload with slight hand-induced curvature so it matches the panel’s intended arc without printing finger pressure. Keep the same cross-hatch pattern but shorten strokes to fit the contour without crossing into adjacent flats.

Finish planning matters. If you’re applying metallics, aim for P400 uniformity under sealer; for solid single-stage, P320 often suffices per system TDS. Before committing to sealer, wipe with wax and grease remover, dry completely, then inspect under raking light at two angles. If reflections still “swim,” go back to P150 with guide—polishing a wave only makes it shinier.

Finally, temperature control counts. Cold panels harden primers and make abrasives skate; hot panels smear. Keep the panel, abrasive, and air within the coating manufacturer’s recommended window. If your hand feels warmth after a few passes, reduce pressure, refresh paper, and clean dust—heat is a reliable indicator you’re sliding instead of cutting.

Block Sanding Primer — Video Guide

The video “Block Sanding Primer - Essential Steps to a Mirror Finish” demonstrates the core workflow after body filler is shaped: using long blocks on primed panels to achieve a flat, reflective surface. It walks through guide coat application, diagonal strokes, and grit sequencing to control both long and mid-wave errors.

Video source: Block Sanding Primer - Essential Steps to a Mirror Finish

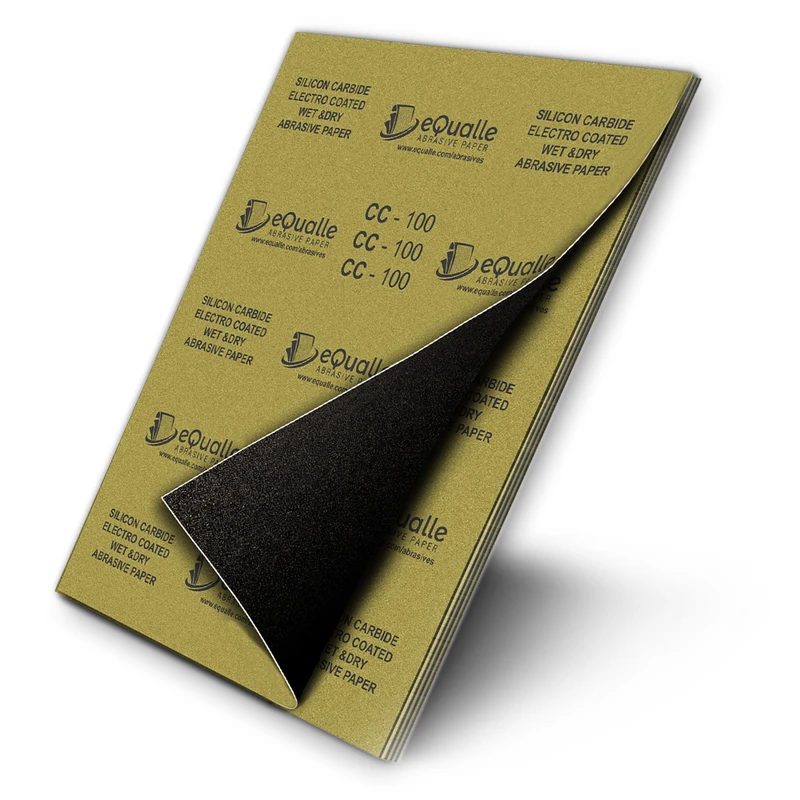

80 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (50-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Durable coarse abrasive that evens out irregular surfaces and clears old coatings. Ideal for early sanding stages in woodworking, fiberglass, or metal preparation. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: How long should my block be to straighten a door skin?

A: Use a rigid 24–30 inch longboard for primary shape. Shorter blocks (8–12 inches) can refine transitions, but they won’t remove long-wave distortion across the panel’s length.

Q: What grit should I start with on high-build primer for waves?

A: Begin with P120–P150 dry using a rigid longboard and a guide coat. Do shape correction at that stage, then refine to P180–P220, and finish at P320–P400 before sealer.

Q: Can I use a soft foam pad to follow slight crowns?

A: Avoid foam during shape correction. Use a thin, semi-rigid board that you can preload to the crown. Foam compresses and rounds, masking lows instead of leveling highs.

Q: How do I prevent flattening a crisp body line?

A: Stack tape over the line during coarse stages, sand parallel to the line with a narrow hard block, and lift off pressure as you cross edges. Unmask for the final grit pass.

Q: Why does the wave reappear after a week?

A: Likely primer or filler shrinkage from under-cure or incorrect mix ratio. Allow full cure per TDS, maintain temperature, and re-block with guide before moving to finer grits.