Sanding Sponge vs Paper on Curves: Pro Results

If you’ve ever stood in your garage at 9 p.m., holding a cup of coffee with one hand and a carved table leg with the other, you know the moment: the curve looks great until you touch it with the wrong abrasive. Flat spots appear, sharp lines soften, and suddenly the piece loses the crisp profile you loved. I’ve been there countless times—chair arms, bowl rims, crown molding returns—each one begging for finesse. The first time I switched from paper to a sanding sponge mid-project, it felt like I’d finally turned down the static and could hear the wood speaking again. The foam hugged the profile, didn’t dig in, and let me smooth without erasing detail.

This article is about that decision point: sponge versus paper on curved surfaces. I’m Lucas Moreno, and in my shop I treat sanding like joinery—it’s a craft of pressure, path, and precision. A good sanding sponge can save an edge you’d otherwise ruin; a well-backed sheet of paper can keep a long, sweeping cove true. Both have their place. The trick is knowing when to deploy each, which grits to choose, and how to move—literally, what direction and what rhythm—to keep your curves elegant, crisp, and ready for finish. We’ll cover real shop techniques, quick tests, and a full step-by-step on a curved chair arm. By the end, you’ll reach for the right abrasive with confidence and stop sacrificing detail for smoothness.

Quick Summary: On curves, a sanding sponge preserves profiles and distributes pressure, while paper—used with the right backers—maintains straightness and sharp edges; use both strategically with controlled pressure and grit progression for flawless contours.

Curves change the sanding game

Curves aren’t just straight lines bent into shape; they change how abrasive pressure interacts with the surface. On a flat, your block or pad spreads force evenly. On a convex or concave curve, you’re creating pressure points—small contact areas that can cut faster than you intend. That’s why flat spots and washed-out details show up so quickly on carved legs, chair arms, and moldings.

Let’s break down what’s happening. A rigid-backed paper behaves like a plane: it bridges highs and misses lows. That can be great for flattening a slightly wavy convex surface, but dangerous when you intend to follow an existing profile. Conversely, a compliant abrasive—like a sanding sponge—conforms to irregularities and distributes force, removing material evenly across the contact patch. This reduces the risk of faceting and helps keep a constant radius.

What matters more than the tool? Your touch. If you press hard at the apex of a curve, you’ll cut disproportionately at that high spot. If you sand across the grain on tight radii, you’ll create scratches that telegraph through finish. The key is controlled pressure, aligned strokes, and a suitable backer.

Three workshop tips to dial in curves:

- Use a pencil guide coat. Lightly scribble the surface before sanding. The pattern tells you where you’re removing material; stop when the coat is uniformly faint, not gone.

- Match the backer to the curve. On tight concaves, wrap paper around a dowel that matches the radius; on gentle convexes, use a soft interface pad or a sanding sponge.

- Slow your stroke near transitions. Where curves blend into flats, lighten pressure and shorten your stroke to avoid rounding crisp lines.

Bottom line: Curves magnify technique. The right abrasive and a steady hand protect the shape you worked so hard to create.

Why a sanding sponge wins on curves

When the goal is preserving a profile, a sanding sponge is my go-to. The foam core acts like suspension on a truck—absorbing micro-variations and distributing pressure over the surface. That means fewer flats on convex moldings, more even scratch patterns in coves, and less risk of rolling an edge.

Sponges shine anywhere you need compliance. On carved details, the foam compresses and rebounds, letting the abrasive make consistent contact without digging in. On inside curves, a radius-edge sponge reaches corners that paper tends to crease or cut. In practice, I’ll grab medium or fine grits (120–220) for shaping and refinement, then jump to 320 for pre-finish smoothing. I avoid super-soft foam for heavy stock removal; instead, I’ll rough-shape with a file or hard-backed paper and switch to the sponge to blend.

Advantages you can feel:

- Edge safety: The foam’s give reduces “hot spots” at corners, so you don’t wash out line breaks.

- Conformability: The sponge hugs tight profiles without splitting or wrinkling like paper.

- Even scratch: Because pressure spreads out, the scratch pattern is uniform, making finish coats lay flatter.

Smart ways to use a sanding sponge:

- Work in arcs along the curve, not straight across it. Your path should mimic the profile you’re keeping.

- Rotate the sponge as you go so you’re not wearing a groove into one spot of the foam.

- Clean frequently. Tap the sponge on your palm or blow it out; loaded grit cuts hotter and streakier.

If you’re fighting flat spots, you’re likely using too rigid a backer or too much pressure. That’s the exact scenario where a sanding sponge earns its place in your kit.

Paper tactics that still matter

Sanding paper hasn’t become obsolete—especially on curves that need to stay true over distance. Think of a long, shallow convex edge on a tabletop or the sweep of a boat gunwale: if you use something too compliant, you’ll mirror the bumps. Paper with the right backer lets you average highs and lows and keep that long line straight.

Here’s how I use paper on curves without losing control:

- Backer choice: On gentle curves, a semi-rigid pad (like a cork block with eased edges) spreads pressure but still conforms. On tighter radii, I swap to a dowel, a soft rubber sanding block with a matching curve, or even a custom MDF form wrapped in thin mousepad foam.

- Paper wrap: Tear paper into narrower strips and wrap it around your backer at a slight bias. This avoids creasing and keeps the abrasive tight as you move. For inside coves, spiral-wrap around a dowel and hold the tail under your thumb.

- Progression: Use slightly finer grits than you would on a flat when you’re near a crisp detail. For example, if you might grab 120 on a panel, choose 150–180 on a carved profile to reduce scratch depth and edge risk.

Three targeted tips:

- Float the edge. When sanding near a sharp line, lift off slightly as you approach it so you don’t “flip” over the edge and round it.

- Use guide blocks. For repeated profiles (cabinet doors, trim), make a template block that matches the curve. Wrap paper, sand a few passes, rewrap, and continue. Consistency skyrockets.

- Avoid finger ridges. Never press with fingertips directly behind paper on curves; you’ll create grooves. Always use some sort of backer—even a folded pad of leather or felt works in a pinch.

Paper remains unbeatable for controlled straightening and for early-stage removal on curves—just keep the backer honest and let the grit, not your force, do the work.

Grits, pressure, and pattern on profiles

The three levers that control curved sanding are grit, pressure, and motion path. Get these right, and your surface will look cut, not smeared, under finish.

Grit selection for curves:

- Shaping: 100–150 grit to fair bumps or blend tool marks. On delicate details, start at 150–180 to avoid accidental reshaping.

- Refining: 180–220 grit to remove shaping scratches and unify the sheen.

- Pre-finish: 320–400 grit (wood) or 400–600 grit (paint/varnish between coats). With a sanding sponge, 320 often leaves a perfect tooth for waterborne finishes.

Pressure control:

- Think “firm handshake,” not “crank bolt.” On a scale of 1–10, keep it at 3–5. If your abrasive isn’t cutting, the grit is wrong or loaded—not your arm.

- Pulse pressure in transitions. As you hit a tight inside corner or a detail change, lighten up for two strokes, then resume.

Motion path on curves:

- Follow the grain where possible, but don’t be afraid to skew 10–15 degrees along the curve to keep scratches from stacking in one track.

- Use short, overlapping arcs on concaves; long, graceful strokes on convex sweeps.

- Reset often. Lift the abrasive, rotate your wrist slightly, and continue. This evens wear and keeps your pattern from grooving.

Troubleshooting checklist:

- Flat spots on a convex: You used a rigid backer or pressed too hard at the apex. Switch to a sanding sponge or add a soft interface pad.

- Washed-out bead detail: Grit too coarse or sponge too soft. Drop to a firmer sponge or move up one grit grade.

- Chatter marks: Paper buckling around the curve. Narrow the strip, bias the wrap, or change to foam-backed abrasive.

According to a article

In practice, a radius-edge sponge gives you two tools in one: flats for blending and a curved edge for inside corners. Pair that with the grit plan above, and you’ll maintain your curves while speeding up the finish cycle.

Wet sanding, dust, and durability

Curved sanding often happens on trim, doors, and chair parts in lived-in spaces—so dust control matters. A sanding sponge has an unsung advantage here: the foam traps a surprising amount of dust before it escapes, and many sponges tolerate light wet sanding that knocks the dust down entirely. Paper can do wet sanding too, but it needs to be labeled for wet/dry use and backed properly so it doesn’t tear.

Here’s my shop routine:

- Dry to shape, wet to refine. I’ll do the bulk of curve blending dry at 150–220. For pre-finish smoothing on paint or varnish, I switch to a fine-grit sanding sponge and a mist of water with a drop of dish soap. The water acts as a lubricant and slurry, giving a glassy, even scratch.

- Rinse to refresh. When a sponge loads, a quick rinse and a squeeze (don’t wring hard; you’ll split the foam) brings it back for another pass. Paper, once loaded, usually stays that way.

- Dust extraction on paper. When using paper on curves with a power sander and interface pad, connect dust extraction and use a foam interface disc to keep the pattern consistent and the air clean.

Durability and value:

- A quality sanding sponge can outlast multiple sheets of paper on curves because it resists creasing and edge tear-out. It’s the creases and folded edges that kill paper first in curved work.

- Store sponges dry and flat, away from heat. If they conform to a weird shape in storage, you’ll be fighting that shape on your workpiece.

Three practical tips:

- Label your sponges. A quick Sharpie mark for grit on the spine saves guesswork mid-project.

- Dedicate sponges to material types. Keep separate sets for raw wood, primer, and topcoat. Cross-contamination introduces scratches.

- Use a light tack cloth after wet sanding once the surface is dry; it lifts the last of the slurry without smearing.

When the job is messy or finish-sensitive, a fine-grit wet-capable sanding sponge is a clean, controlled way to finesse curves without filling the room with dust.

Step-by-step: refinish a curved chair arm

Let’s put it all together with a project I’ve run in both client work and weekend fixes: refinishing a curved chair arm with a subtle cove and a proud bead at the edge.

Tools and materials:

- Sanding sponges: medium (150), fine (220), extra-fine (320)

- Paper sheets: 150 and 180 grit

- Backers: 3/4-inch dowel, cork block with eased edges

- Pencil, tack cloth, water spray bottle with a drop of dish soap

- Optional: foam interface pad and 5-inch sander if the curve is gentle

Steps:

- Inspect and mark. Wipe the arm clean. Use a pencil to mark out scratches, nicks, and any shiny finish left. Lightly scribble a guide coat over the entire arm.

- Protect the bead. Mask just past the crest of the bead if it’s especially crisp. This gives you a visual stop line and a small margin of safety.

- Fair the long curve. Wrap 150-grit paper around the cork block and take five long passes along the convex sweep, following the grain and curve. Lift between passes. You’re flattening bumps without changing the radius.

- Blend the cove. Switch to the 3/4-inch dowel wrapped with 150. Work in short arcs along the inside curve. Keep strokes light; if the pencil coat disappears evenly, stop.

- Switch to the sanding sponge. Grab a 220 sanding sponge and run it along the entire arm—cove, bead shoulder, and convex face—in continuous strokes. Rotate the sponge as you go. This unifies the scratch and removes any facets from the previous step.

- Preserve the bead. Using the corner of the 220 sponge, tickle the bead lightly—two or three passes max. If the bead starts to look soft, stop and use a tighter paper wrap around a small dowel to crisp the engagement line without touching the crest.

- Pre-finish smoothing. Mist the surface lightly and run a 320 sanding sponge with just enough pressure to float. Aim for a uniform, matte sheen.

- Clean and inspect. Dry the arm, tack cloth it, then inspect under raking light. If any pencil marks or shiny spots remain, address them with the 220 sponge and repeat the 320 pass.

- Finish. Apply your chosen finish. If you’re sanding between coats, use 400–600 grit wet with a fresh fine sanding sponge to level without cutting through edges.

Common pitfalls and fixes:

- Flat spot near the apex: You lingered with a rigid backer. Rebuild the curve by feathering with a medium sponge, then refine.

- Rounding the bead: Grit too coarse or too much pressure. Mask closer to the edge and use the edge of the sponge, not the face.

- Uneven sheen after finish: Scratches didn’t unify. Re-sand with 220 sponge across the whole profile, then repeat the 320 pre-finish.

Three final tips for chair arms:

- Support the work. Clamp the chair or brace it against your hip so both hands can control the abrasive.

- Count strokes. Symmetry matters on left/right arms; match your passes to keep profiles identical.

- Let the grit do it. If you’re sweating, you’re forcing it—go finer or clean the abrasive.

Norton ProSand Sanding — Video Guide

There’s a short demo highlighting pro-grade foam abrasives titled along the lines of Norton ProSand Sanding Sponges. The clip shows how sharp, long-lasting grains paired with quality foam make finishing faster and more consistent, especially on contoured surfaces and moldings.

Video source: Norton ProSand Sanding Sponges

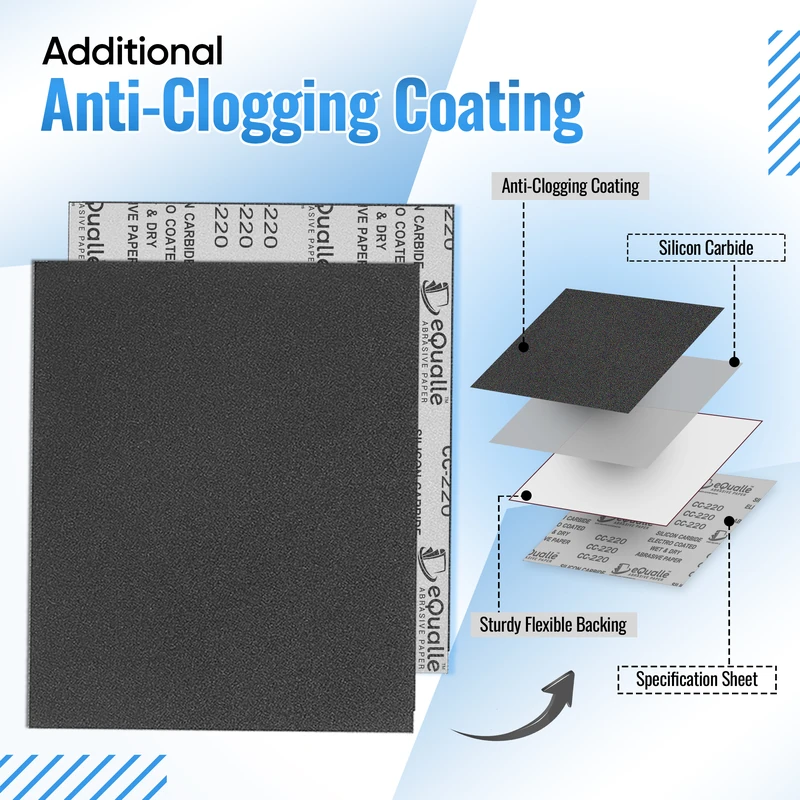

80 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (10-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Durable coarse abrasive that evens out irregular surfaces and clears old coatings. Ideal for early sanding stages in woodworking, fiberglass, or metal preparation. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: When should I choose a sanding sponge over paper on curves?

A: Use a sanding sponge when preserving a profile matters—carved details, inside coves, and any curve where flat spots are a risk. Paper is best with a matched backer for fairing long, gentle curves or for initial shaping before switching to a sponge to blend.

Q: What grit sequence works best for curved wood surfaces?

A: Start at 150–180 for shaping, move to 180–220 to refine, and finish at 320 before coating. For between-coats on paint or clear finishes, use 400–600 wet with a fine sanding sponge.

Q: How do I avoid rounding crisp edges and beads?

A: Float pressure near edges, use a firmer sponge or a properly backed paper wrap, and sand up to the line—not over it. Mask close to the crest for a visual stop, and use the sponge’s edge sparingly to “kiss” the detail.

Q: Can I wet sand with any sanding sponge?

A: No. Use sponges labeled for wet/dry work. Lightly mist the surface with water and a drop of soap, then rinse the sponge occasionally to prevent loading. Let the workpiece fully dry before finishing.

Q: Why does my paper crease and leave chatter on curves?

A: The paper is wrapping too sharply or is too wide for the radius. Tear narrower strips, bias the wrap, and use a matching backer like a dowel or a foam interface. If chatter persists, switch to a sanding sponge to even out the pattern.