Sandpaper Grit Chart: Verify Scratches Before Upgrading

On a quiet Saturday morning, you clamp down a panel you’ve been saving for a fresh finish—maybe a guitar body, a dresser drawer front, or a primered door skin. Coffee’s cooling. The shop is clean, the plan is set, and your stack of abrasives sits like a neatly organized ladder next to your bench. You’ve mapped your progression: P120 for shaping, P180 to refine, P220 to remove print-through, then P320 for primer surfacing. A sandpaper grit chart is within reach, annotated with your go-to sequences. The temptation is strong to move briskly through those steps. After all, each finer grit will “clean up” the last, right?

But as you rotate the piece under raking light, you spot it—one low arc that catches the angle differently. It looks faint, barely there, easy to ignore. That faint arc is a deeper valley from your previous pass, and if you jump ahead now it will migrate through your entire workflow. Hours later, after paint or oil or clear coat, it will telegraph back as a ghost line. What you do next—right now—determines whether you end today with a flawless substrate or a perfectly polished mistake.

Verifying scratch removal before you move up is not superstition; it’s process control. Grit numbers on a sandpaper grit chart tell you expected cut and finish, but they don’t guarantee uniformity. The actual surface state depends on pressure, dwell time, abrasive friability, loading, and material response. The master craftsperson doesn’t rely on grit alone—they run a disciplined verification routine at every transition. With the right sequence, lighting, and tests, you’ll stop carrying defects forward and start finishing faster, not slower.

Quick Summary: Don’t move up a grit until your verification routine proves every previous scratch is erased; light, direction, witness marks, and solvent wipes are your proof.

Why Scratches Hide Between Grits

Scratches persist through grit changes due to geometry and mechanics. A coarse grit creates valleys deeper than their width; a finer grit then rides the peaks, burnishing rather than excavating those valleys. This “bridging” effect leaves legacy scratches barely visible until a finish magnifies them. On wood, early/latewood density swings amplify it; on metals, burnishing can produce false sheen that masks valleys. Plastics add another trap—heat softening and smear can round peak edges, making valleys harder to see yet impossible to remove without cutting back aggressively.

Random orbital sanding introduces its own challenge: pigtails. A single embedded particle or loaded grain can plow a spiral that survives three grit steps if you don’t detect it under raking light. Pressure profiles matter, too; an interface pad on a DA can conform around low spots, reducing local pressure and skipping the very areas that need cut. Excessive pressure or clogged discs “skate,” burnishing peaks and reducing cut rate. Conversely, too little pressure reduces friability (grain fracturing), so the abrasive stops refreshing its cutting edges and starts polishing.

Another common culprit is cross-contamination. One rogue P80 particle on your P220 disc will seed deep gouges in a field of fine scratches. Dust management and pad hygiene are not cosmetic—they’re core to scratch removal. So is planarity. If the work surface isn’t flat to the backing, you’ll achieve a deceptive sheen with islands of uncut coarse scratches living in low areas. At transitions—say P120 to P180 on primer or sealer—establish a clearance step: remove enough material to level the topography left by the last grit. When that step is rushed, you end up applying more passes at higher grits with lower removal rates, multiplying time and still missing the valleys.

The physics is unforgiving: removing a P120 valley with P220 can take 4–6 times longer than with P150, and even then, you risk burnishing rather than cutting. The solution is controlled verification at each step, not optimism.

Visual and Tactile Verification Methods

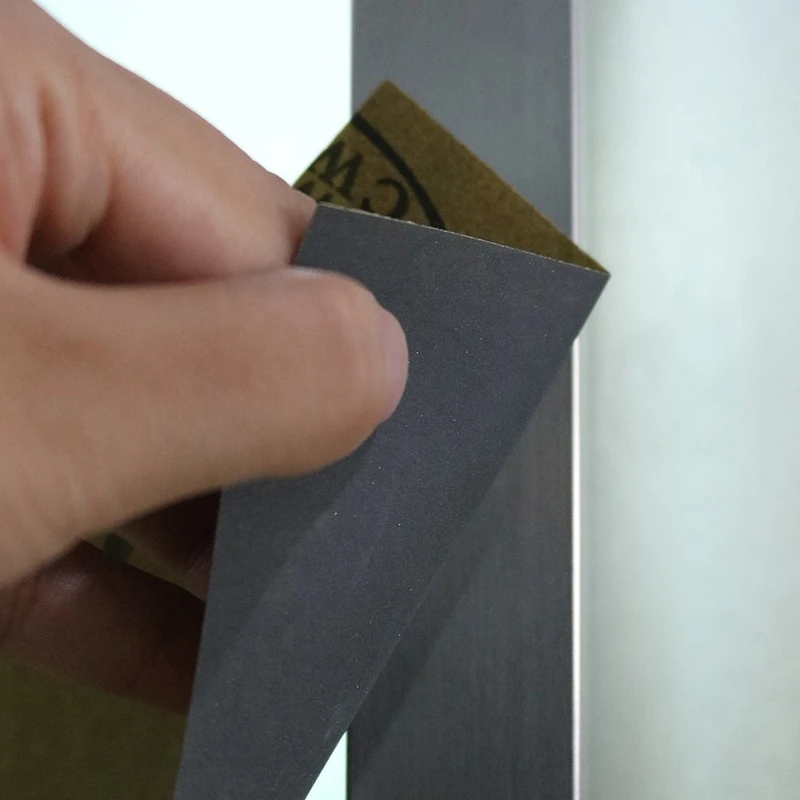

Eliminate guesswork with a repeatable verification routine. This is a metrology mindset—simple instruments and controlled viewing amplify your ability to see what the naked eye misses. Start by changing direction between grits. If you sand with P120 north–south, run P150 east–west; the cross-hatch makes legacy scratches immediately obvious. Then deploy raking light at a shallow angle (15–30 degrees). A handheld LED bar or adjustable bench light will reveal valleys as differently reflective lines. Don’t flood the area with diffuse light—shadows are your friend.

Use witness marks. Cover the field with a light pencil crosshatch before you start the next grit. Your goal is removal of every line, not most of them. In curved or complex geometries, switch to shorter blocks and smaller interface pads to keep pressure focused and maintain conformity without bridging low spots. A solvent wipe (naphtha or mineral spirits for wood, panel prep for metals) temporarily darkens the surface and reduces chalky dust, increasing contrast so hidden scratches pop. On glossy plastics, a rubber squeegee pass over a water-wet surface does the same.

Magnification helps. A 10x loupe or clip-on macro lens on a phone lets you inspect the scratch field for stragglers. For metals and solid-surface composites, push to a slurry stage at higher grits; the uniform paste reveals islands of coarser texture instantly.

Actionable tips for reliable transitions:

- Use a pencil crosshatch before each new grit and don’t move on until 100% of it is erased.

- Alternate sanding directions by 90 degrees between grits to expose legacy scratches.

- Inspect under raking light at 15–30 degrees; rotate the work 90 degrees and re-check.

- Perform a fast solvent or water squeegee wipe to boost contrast before deciding to move up.

- Check with a 10x loupe at three points: center, edges, and any low areas or repairs.

If any witness remains, don’t “chase” it at a finer grit. Drop back one grit and re-establish a uniform field. This is faster than spending ten minutes trying to erase a P120 scratch with P220.

Reading a sandpaper grit chart in practice

A sandpaper grit chart outlines relationships between CAMI and FEPA (P-scale) numbers, and sometimes microns for micro-abrasives. But the numbers are not interchangeable one-to-one. For example, P150 (FEPA) has a different average grain size and distribution than CAMI 150. Micro-mesh and lapping films (rated in microns) further complicate transitions. Professionals think in removal capacity and scratch depth: each step should reduce average scratch depth by roughly 40–60% without leaping so far that it takes excessive time to clear the previous pattern.

Practical mapping looks like this for raw hardwood: P80 to flatten and remove mill marks; P120 to clear P80 quickly; P150 or P180 to refine for stain; P220 only if the species and finish benefit. For automotive primer: P120 for shaping filler, P180 to establish contour, P220–P320 to prep for primer surfacer, P400–P600 for sealer, and P800–P1000 for color/clear. On bare aluminum or brass: start at the finest grit that still removes oxidation within a reasonable number of passes, then step through P400, P600, P800, P1000, and into microns for polish.

According to a article

The chart is your roadmap, but verification is your speedometer. Limit jumps to a factor of 1.5–2 in scratch depth: P120 to P180 is safe; P120 directly to P240 is often slow and risky unless the substrate is soft and flat. For micro-finishing (e.g., between coats), use films with known micron ratings so you can target specific Ra ranges. In all cases, stop treating the chart as a checklist and start using it as a hypothesis you continuously test. If you’re spending more than 60–90 seconds at a finer grit clearing a legacy scratch, you skipped an intermediate. Drop back, cut decisively, re-verify, and move forward.

Also note how open-coat vs closed-coat paper and stearate loadings affect scratch morphology. Open-coat papers reduce loading on softwoods and paints but can leave a slightly more erratic pattern; closed-coat cuts faster with a more uniform field on metals. Align your chart selection with abrasive construction, not just the printed number.

Workflow Controls That Prevent Rework

A flawless finish is the product of controls as much as technique. Start with zoning. Divide panels into quadrants and complete verification per zone before moving on; this prevents the classic “I thought I got that corner” problem. Timebox your passes—15 to 30 seconds per 12x12 inch area at each grit—with machine speed and pressure held constant. Consistency produces predictable scratch fields and makes deviations obvious.

Standardize pressure. With a 5- or 6-inch DA on a firm pad, aim for roughly 2–3 kg of downforce—enough to engage cutting without stalling orbit. Let abrasives cut; heat is a warning. If the work becomes more than warm to the touch, you’re likely burnishing or loading. Replace discs early; by the time a disc looks dull, it’s been underperforming for minutes and making scratch removal slower. Clean between grits. Vacuum, blow off with filtered air, and wipe the pad. One coarse grain embedded in a P320 disc creates a pigtail that survives into P600.

Control contamination. Keep discs by grit in separate sleeves or color-coded bins. Never set a used coarse disc on the bench where finer discs live. For wet work, dedicate buckets and squeegees per grit to avoid carrying abrasive slurries forward. Track temperature and humidity when finishing; solvent pop and dieback issues can mask or accentuate scratches post-coating, making post-cure sanding longer.

A simple checklist laminated at your bench helps:

- Mark the zone.

- Crosshatch and cut.

- Raking light check (two orientations).

- Solvent or squeegee wipe.

- Loupe inspection.

- Clean pad, vacuum dust, change disc if in doubt.

Build these controls into your cadence. They take seconds but save hours. Over time, you’ll notice fewer callbacks to earlier grits, fewer “mystery lines,” and faster progressions with confidence.

What grits of — Video Guide

Brad’s concise video on selecting sandpaper grits for painting workflows walks through practical step-ups from coarse to fine, demonstrating where to start, when to switch, and how to avoid over-sanding between coats. He frames grits in context—bare substrate, primer prep, and pre-clear—so you see why each stage has a different target scratch profile.

Video source: What grits of sandpaper should you use when painting

60 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (50-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Extra-coarse Silicon Carbide abrasive for rapid stock removal and reshaping. Excels at stripping paint, smoothing rough lumber, or eliminating heavy rust on metal surfaces. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: How do I know when P120 scratches are fully gone before switching to P180?

A: Change sanding direction 90 degrees, apply a pencil crosshatch, and inspect under 15–30 degree raking light. If any linear marks aligned with the P120 pass remain or any pencil lines persist, stay at P120. Use a loupe on suspect areas and re-check after a brief solvent wipe for contrast.

Q: Does wet sanding make it harder to see remaining scratches?

A: Water or panel prep can temporarily mask scratches by filling valleys. Always squeegee or wipe dry and re-inspect under raking light. Alternating between wet and dry checks is effective: wet to reveal uniformity in the slurry, dry to catch contrast-based defects.

Q: Can I skip from P150 to P320 to save time?

A: Only if the substrate is very soft and flat and your P150 field is perfectly uniform. In most cases, you’ll spend more total time at P320 clearing P150 scratches than you would taking a P220 intermediate. Limit jumps to about 1.5–2x in scratch depth reduction and verify thoroughly.

Q: How much pressure should I use with a DA to avoid burnishing?

A: Target roughly 2–3 kg of downforce with the machine at moderate speed, letting the abrasive cut. If the pad stalls or the surface heats quickly, reduce pressure. Replace or clean loaded discs; loading is a common cause of burnishing and false “finished” look.

Q: When should I replace a sanding disc if it still looks okay?

A: Replace at the first sign of reduced cut rate or rising temperature, not when it’s visibly worn. Time-bound usage helps: for example, 3–5 minutes of active cutting on P120 for a panel area, less at finer grits. A fresh disc is cheaper than rework.