Boat Sanding and Smooth Fairing Before Primer

You can hear it before you see it: the soft rasp of paper across gelcoat, the shush-shush rhythm that turns a scuffed hull into something you can be proud of. Boat sanding isn’t exactly glamorous, but on a still morning—coffee perched on a dock post, gulls trading gossip overhead—it feels like craft. Your fingers become the first inspectors, gliding across highs and lows. The goal isn’t just clean; it’s consistent. When you’re aiming for smooth fairing compound before primer, you’re making a commitment to what comes next: paint that lays down like glass, reflections that don’t ripple, and time on the water that starts sooner because you did the prep right.

You start with a plan. Where the hull waves, you won’t sand it flat by brute force; you’ll fair it into plane. Where pinholes dot the surface, you’ll fill, not chase them with endless paper. The difference between a “good enough” refit and a gleaming finish is the base you create long before paint arrives. Fairing compound is the sculptor’s clay, and sanding is your chisel. In the right order, with the right touch, everything downstream gets easier—primer bonds better, paint flows longer, and the surface resists telegraphing. In the wrong order, you’ll fight sags, orange peel, and that cruel raking light that shows every shortcut.

Maybe you’ve been here before: the day you decided to stop masking flaws and start fixing them. The hull doesn’t lie. It reflects every part of your process—especially the parts you tried to rush. The good news is that fairing and sanding follow a rhythm. Mix, spread, shape. Guide coat, sand, check. Prime within the window. It’s calm, repeatable work that rewards patience. And when you launch, the shine won’t just be cosmetic—it’ll be the visible proof of a sound, well-prepared surface.

Quick Summary: Build a flawless, paint‑ready hull by fairing first, then using guided sanding sequences and proper timing to prime over an ultra‑smooth, stable base.

Why a flawless base matters

Primer can’t fix shape; it only smooths texture. That’s why fairing happens before primer and why the fairing must be truly smooth. Paint and primer are thin films, and films telegraph: any hump, hollow, or pinhole becomes a visible defect once color hits. A fair surface spreads stress evenly, reduces drag, and gives your primer a consistent bite, so you don’t see patchy gloss, sink‑back, or witness lines after curing.

Fairing compound is not a generic filler; it’s engineered to feather easily and sand predictably. When you lay it in strategic passes, you’re correcting long‑range waviness—not just pockmarks. Think in planes, not spots. Longboarding brings the whole surface into one conversation; a random orbital alone speaks in local dialects. If you rely on primer to hide shape issues, you’ll stack unnecessary thickness, add weight, and still see the undulations once light rakes across the hull.

Moisture sensitivity and cure state also matter. Epoxy‑based fairing compounds need time and the right temperature to fully set. Sanding too soon gums up paper and pulls the surface, creating a fuzzy texture that defeats your effort at smoothness. Sanding too aggressively can “dish” soft areas and round hard edges, compromising fair. A stable, well‑cured fairing base lets your primer crosslink as intended, improving adhesion and reducing the risk of delamination or print‑through.

Ultimately, the smoothness you aim for before primer sets the ceiling for your final finish quality. The less you demand from primer, the better primer performs. Keep fairing compound within the fair zone (choose the least material to reach true shape), then refine until your surface moves from fair to smooth: no ridges, no edges, no pinholes, and a consistent scratch pattern that’s easy for primer to cover.

Tools for boat sanding and fairing

Great results come from simple tools used well. For hull and deck surfaces, start with a longboard—a 24–36 inch board with a bit of flex—to bridge highs and lows and reveal the true surface. Pair it with PSA or hook‑and‑loop paper in grits from 60 to 220. A random‑orbital or dual‑action sander with dust extraction speeds up leveling and finish sanding, but treat it as a complement to, not a replacement for, the longboard.

A fairing batten (a thin, flexible strip) helps you read curves and locate hollows before they become paint problems. Use raking lights or a bright LED held low to catch shadows that eyes miss. For the compound itself, keep clean mixing boards, calibrated measuring cups or a small scale (if mixing by weight), and a set of flexible spreaders and wide putty knives. A notched spreader can help gauge thickness on flat stretches; a wide squeegee acts like a mini‑screed on gentle curves.

Plan on guide coats—light mists of contrasting spray that settle in low spots and pores. They’re your map during sanding. Keep fresh paper on hand; dull paper rides over defects and burns through highs. A soft interface pad for your sander helps follow subtle curves without digging.

Don’t ignore environment and safety. Epoxy likes 60–80°F and steady humidity; too cold, it won’t cure right; too hot, it kicks too fast. A hygrometer and infrared thermometer are cheap insurance. NIOSH‑approved respirator cartridges for organic vapors and particulates, nitrile gloves, eye protection, and good ventilation are non‑negotiable. Collect dust at the source—it’s cleaner, safer, and lets your paper cut longer. Organize your station so resin, hardener, and tools never cross‑contaminate with solvents or sanding dust. In short, set the stage, and the work flows.

Mix, spread, and shape fairing

Consistency and control make fairing predictable. Start by mixing your two‑part epoxy fairing compound precisely to the manufacturer’s ratio. Mix on a flat board by folding and smearing with a wide putty knife until color is uniform, minimizing trapped air. Target a spreadable, peanut‑butter texture—soft enough to pull in long strokes, firm enough not to slump on verticals. Temperature affects viscosity; warm resin flows more, cool resin stays put. Adjust your shop, not the ratio.

Apply in thin, strategic lifts. Think in passes: long, diagonally oriented pulls that follow the hull’s natural fair. Use the widest spreader you can comfortably control; widen on flats, narrow on tight radii. Feather edges gently so you’re not creating ridges that need aggressive sanding later. On large hollows, trowel a first coat to fill 70–80% of the depth, let it cure, then bring it home with a second application rather than overfilling and sanding a mountain.

Let it reach true sandability. Test an off‑to‑the‑side dab—if paper loads immediately or the surface feels rubbery, wait. When cured, knock down ridges with 80‑grit on a longboard, then use your guide coat and cross‑hatch passes (45° one way, 45° the other) to keep the surface honest. Repair pinholes and pores with a skim coat, squeegeed tight so you’re filling voids, not adding thickness.

According to a article.

Between passes, clean with a dry brush or vacuum rather than solvents, which can soften or contaminate uncured epoxy. If you must wipe, use the system’s recommended solvent and allow complete flash‑off before the next coat. Continue building in controlled layers until the surface is both fair (correct shape) and smooth (consistent micro‑texture). The smoother you get now, the fewer primer coats you’ll need later.

Sanding sequences that stay fair

Your sanding sequence should preserve shape while refining texture. Start coarse enough to level without grinding: 60–80 grit for first cuts on cured fairing compound. Work on the longboard in cross‑hatch patterns, shoulder to shoulder with the hull’s curves. Use a guide coat so you can see what’s actually happening—lows stay dark, highs go light. Avoid chasing one spot; widen your strokes to blend transitions.

Once the surface is uniformly leveled, step to 120–150 grit to erase deep scratches and refine the profile. Still use the longboard wherever possible; the random‑orbital can handle edges, small features, and smoothing between passes. Finish pre‑primer sanding at 180–220 grit for most epoxy primers. Check your primer’s datasheet—some prefer 120–150 for mechanical tooth, others tolerate 220 just fine.

Control pressure, not just motion. Let the paper cut; if you bear down, you dish soft areas and round over crisp design lines. Protect sharp corners with a double layer of tape while you sand broad fields; remove it for a few light blending strokes at the end. Keep paper fresh—once it stops cutting, it polishes highs and leaves lows untouched.

A few actionable tips:

- Use a dry guide coat powder or a light mist of contrasting spray paint every time you change grits; it’s cheap accuracy.

- Mark known lows with a wax pencil before sanding; after a couple of passes, confirm they’re shrinking evenly rather than migrating.

- Tape a thin batten along suspected wavy runs and sight it under raking light; sand until the batten sits evenly with no daylight gaps.

- Vacuum after each grit and inspect with a bright light at a low angle; dust hides defects and clogs fresh paper.

- For edges and tight radii, wrap paper around a soft, shaped block instead of using fingertips to avoid grooves.

Wet sanding has its place, mostly later with cured primer and paint. On uncapped epoxy fairing compound, stay dry unless the product explicitly allows wet sanding; moisture can interfere with cure and adhesion. Keep the discipline: guide, sand, check, repeat.

Primer prep, timing, and checks

The handoff from fairing to primer is where many projects stumble. Start by verifying cure: if your fingernail can dent the fairing surface, it’s too green. Lightly scuff any glossy spots with 150–180 grit to ensure even tooth. Remove dust by vacuum and a clean microfiber; avoid tack cloths that can leave residue unless your primer system approves them. Dew point matters—prime when the substrate temperature is at least 5°F (3°C) above dew point to prevent condensation.

Choose a compatible high‑build epoxy primer to lock in the work you’ve done. These primers fill fine scratch patterns and unify porosity, giving your topcoat an even base. Apply 2–3 medium coats within the recoat window to maintain chemical adhesion between passes. If you miss that window, sand per the datasheet, typically with 220–320 grit, and resume. Roll‑and‑tip works well for many; spraying provides the most uniform film but demands control and PPE.

After your first primer coat, use another guide coat and longboard lightly with 220–320 to identify remaining nibs, micro‑lows, or pinholes. Spot fill stubborn pinholes with a compatible, fast‑curing glazing putty from the same system, then reprime those areas. Don’t overbuild primer to hide shape; if a low is more than a few mils, return to fairing compound for a quick touch‑up, then re‑prime.

Final checks are tactile and visual. Close your eyes and run fingertips across suspect seams; your sense of touch catches transitions sight can miss. Sight along the hull under raking light to ensure highlights move in a clean, unbroken line. When the surface looks boring—no shadows, no surprises—you’ve won. That’s the moment to move forward confidently to topcoat, knowing your finish will reflect craft rather than compromise.

Wet Sanding vs. — Video Guide

If oxidation or chalky gelcoat is part of your project, a concise refresher helps. In a recent walkthrough from a pro detailer, you’ll see wet sanding and dry sanding compared in real time—when to choose each method, how grit selection changes outcomes, and how to avoid burning through gelcoat or compounding swirl marks downstream. The demo emphasizes controlled pressure, smart grit jumps, and clean inspection between passes.

Video source: Wet Sanding vs. Dry Sanding Explained | Boat Detailing Tips

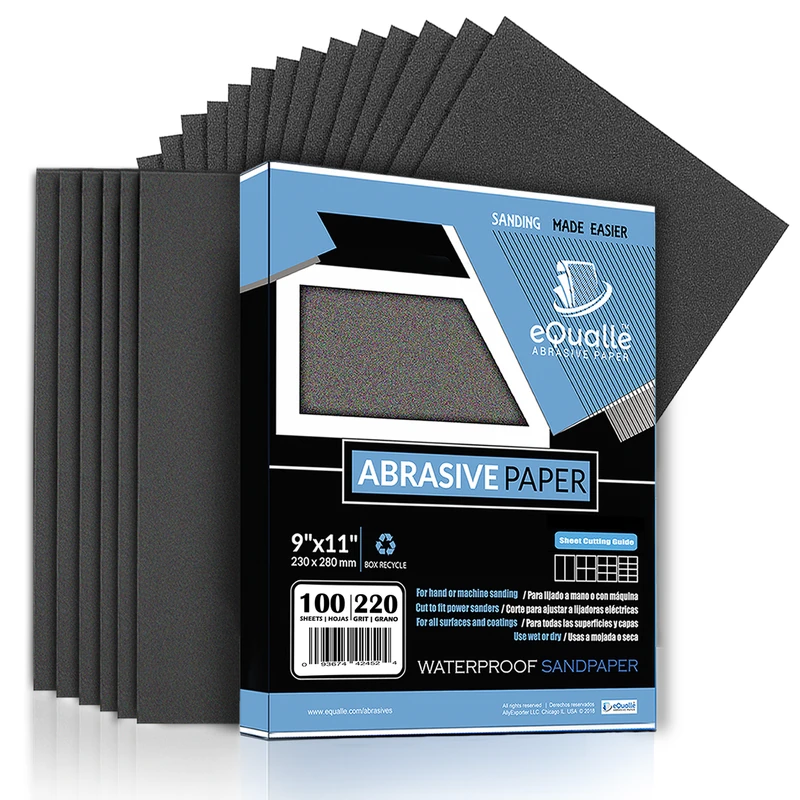

150 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (25-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Versatile medium grit that transitions from shaping to smoothing. Works well between coats of finish or for preparing even surfaces prior to paint. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What grit should I finish at before applying epoxy primer?

A: Most high‑build epoxy primers like a 180–220 grit finish on fairing compound. Check your primer’s datasheet; some systems prefer stopping at 150 for better mechanical tooth.

Q: Do I need to seal fairing compound before primer?

A: Not usually. A compatible epoxy primer serves as the sealer. Ensure the fairing is fully cured, dust‑free, and uniformly sanded. Only add a separate sealer if your coating system specifies it.

Q: Can I wet sand fairing compound to speed things up?

A: Avoid wet sanding uncapped epoxy fairing compounds unless the product explicitly allows it. Moisture can disrupt cure and hurt adhesion. Save wet sanding for cured primer or topcoat stages.

Q: How do I know when to add more fairing vs. just priming?

A: If guide coat reveals lows you can still feel or that persist after a couple of longboard passes at 120–150 grit, add a thin fairing lift. Primer should fill only micro‑texture, not correct shape.