Wet Grinding Slurry Control for Concrete Polishing

It’s 6:10 a.m. in a silent warehouse. Air is cool, lights are still buzzing to full brightness, and the crew is rolling out hoses and laying edge-protection mats with the practiced choreography of a hundred previous jobs. The general contractor walks the space with a client, tracing imagined traffic patterns in the air: this will be a public lobby, high reflectivity, no coating, a breathable sheen that wears in gracefully, not off in flakes. On-site expectations like these live or die by process discipline. Everyone agrees on the end state—clean clarity, sharp aggregate reveal—but the real determinant of that result begins long before the burnish. It starts with water, abrasives, and the wet byproduct the team will generate hour after hour. It starts with slurry.

If you’ve spent enough nights on slab, you know the paradox: wet grinding is clean, cool, and fast—until slurry overwhelms you. Pumps can’t keep up, vacuums clog, and head pressure floats as the pad hydroplanes on a film of fines. Scratch patterns blur, segments glaze, and the gloss meter tells the truth. That’s why senior crews talk about “slurry discipline” with the same gravity as bond selection. In concrete polishing, the difference between a mirror and a matte often hinges on how precisely you meter water, how consistently you evacuate fines, and whether your team treats slurry like another abrasive in the stack—not waste, but a force to be managed.

The room warms; grinders spin up. The lead operator lifts a palm, checks the slab temperature, and signals, “Water on.” It’s not random. Flow rate, pH, and solids loading are calibrated against substrate hardness and tool bond. Squeegees and berms are staged before the first pass. When the slurry flows, it’s guided, dewatered, and neutralized with intent. That’s how you keep the pad in the cut, maintain scratch integrity, and deliver a finish that keeps its clarity under daylight—start to finish, with no surprises at punch.

Quick Summary: Control slurry thickness, chemistry, and evacuation during wet grinding to stabilize abrasive cutting, preserve scratch fidelity, and deliver consistent, high-gloss results.

Why slurry control defines the finish

Slurry is not just waste; it’s an active participant in the cut. The water-cement fines mixture forms a boundary layer beneath the tool. Too thin, and you overheat segments, accelerate wear, and micro-fracture the surface. Too thick, and you hydroplane—smearing fines, rounding scratches, and stalling removal rates. The sweet spot is a uniform, low-viscosity film that cools and carries fines to collection without cushioning the diamonds from the substrate.

Scratch preservation depends on managing this film. Metals at 30–70 grit should evacuate heavy stock. If slurry pools, those coarse fines re-enter the interface and behave like uncontrolled abrasives, randomly scouring the surface and widening the scratch field. That cascade degrades the efficiency of your subsequent grits, forcing extra passes to re-establish clarity. Conversely, in mid-grit transitions (100–200 metal or transitional hybrids), a slightly more stable fluid layer can help attenuate chatter while still transporting fines, provided extraction is frequent and consistent.

Tool behavior changes as slurry concentration rises. Diamonds glaze when the binder is starved of pressure and traction; you’ll see a mirror on the segment face and feel drag with minimal cutting. Operators sometimes respond by increasing downforce, which briefly restores bite but drives heat into a slurry-rich interface, compounding glazing. The fix is process, not force: reduce water flow, skim and vacuum, then resume with a renewed boundary layer.

Edges and joints amplify these dynamics. Slurry tends to accumulate at perimeter runs and recesses, increasing cushion and contamination just where the scratch profile is easiest to disrupt. Match your main-head passes with timed edge extractions. Keep the edge tools on the same rinse/vacuum cadence as the primary grinder. When slurry control is synchronized across the entire field, the finish reads as one surface—no cloudy edges, no “ghost” lanes.

Wet grinding chemistry and fluid dynamics

Fresh cementitious slurry runs alkaline, often pH 12–13. That chemistry matters. Highly alkaline water can saponify certain oils and softeners, leaving residues that interfere with densifiers and colorants. It also affects flocculation: polymers and coagulants designed to agglomerate fines have optimal pH windows; outside those, you’ll need more product for less effect. Monitor pH during long runs—temperature, admixtures, and aggregate fines can shift it over the day. Neutralization later is about compliance, but pH now is about process stability.

Fluid dynamics at the tool interface are plain physics. The rotating head shears the fluid; viscosity and solids loading dictate whether the layer is lubricating or cutting. A laminar, low-solids layer promotes consistent contact between diamond and substrate; turbulence and high solids reintroduce randomness. Aim for a controlled film: approximate flow at 0.2–0.4 L/min per head for coarse cuts on dense concrete, increasing slightly on softer substrates that generate fines rapidly. Water hardness matters too; high calcium can edge the slurry toward faster agglomeration and unexpected thickening. If local water is very hard, consider softened makeup water for more predictable rheology.

Rheological modifiers—superabsorbent polymers (SAP), coagulants, or flocculants—are not just for disposal. Strategically applied, they can “thicken out” pooled zones to prevent backflow into the cutting path, especially in low-slope areas. But moderation is critical; over-application near the interface will starve the cut. Keep additives in auxiliary berms and collection zones, not under the head.

Heat is both output and signal. As slurry loads increase, friction decreases but segment temperature can paradoxically rise due to skating and dwell. Use IR spot checks: when metal segments creep above 65–75°C under wet conditions, you’re in a glazing regime. The remedy is to evacuate slurry, reset flow, and restore pressure/velocity balance, not just douse with more water. Keep your evacuation equipment matched to your production rate; collection should remove at least 80–90% of generated slurry within one pass window so the interface sees new water, not recirculated fines.

Abrasive selection for concrete polishing workflows

Your abrasive stack determines how tolerant your process is to slurry variance. In concrete polishing, the opening cut with metal bonds must prioritize controlled chip formation and efficient fines removal. Choose bond hardness based on aggregate hardness and cement matrix. On hard, dense slabs with quartz or granite aggregates, softer metal bonds expose fresh diamonds under moderate pressure, sustaining cut despite low fines generation. On softer concrete, go harder in the bond to prevent rapid diamond release and mudding.

Grit progression sets your slurry profile. At 30/40 grit metals, you’re producing coarse fines and slurry with higher sedimentation rates—this is the stage where under-evacuation causes the worst hydroplaning. Maintain lower flow and higher vacuum frequency. By 70/80 and 100/120 metals, fines are smaller and more stable; controlled flow with timed squeegee pulls can stabilize the interface. Transitional tools (hybrid resins) bridge into resins while resisting slurry-induced glazing. Once in resin bonds, keep the film thin enough to avoid smearing; resins are more sensitive to hydroplaning, especially in the 100–200 range.

Load, speed, and pattern are your levers. Keep head pressure within manufacturer window, typically 1.5–2.5 psi at the interface for mid-weight planetary machines, adjusting for tool area. Surface speed in the 350–550 rpm range (or 150–190 rpm on large-planets with higher peripheral velocity) balances cut and heat for wet passes. Spiral or overlapping racetrack patterns with 1/3 to 1/2 pass overlap maintain uniform slurry thickness and scratch density.

Actionable tips:

- Set a “slurry window” per grit: if the squeegee leaves a continuous opaque trail thicker than 1–2 mm, pause and evacuate before continuing the pass.

- Blue-tape the machine skirt with 2–3 relief slits; this vents mist but prevents slurry blowout that re-enters the cut from the perimeter.

- Dress glazed metals on a sacrificial paver or use a dressing stone between passes; do this immediately after noticing temperature rise or drag, not at the end of a run.

- Meter water with a needle valve and record flow per tool per grit; repeatability beats guesswork, especially on large projects.

According to a article. The right chemical aids and absorbents can extend tool life and keep the process predictable, but they only perform when integrated into a disciplined workflow.

On-site slurry handling: gear and steps

Effective slurry management is a portable factory within your jobsite. Treat it as a separate operation that runs in lockstep with grinding. Core components include: a wet vacuum with cyclonic separation or bag filter pre-stage; squeegee teams equipped with berms or foam dams; drums or IBC totes labeled for pH and solids; and a dewatering solution—filter press, filter bags, or SAP-lined bins—matched to your production rate.

Workflow steps:

- Pre-stage containment. Install flexible berms to direct flow toward collection lanes. Protect drains—no process water to storm inlets. Lay down edge barriers where slab slope concentrates runoff.

- Calibrate flow and vacuum cadence. Assign a tech to follow the grinder’s tail by one lane, pulling slurry via wide squeegees into vacuum pickups. The target is “no standing pools” two passes behind the grinder.

- Dewater continuously. Decant vacuum canisters into filter bags or a press. If using SAP, dose only the collection bins, not the floor. Aim for a cake with <50% moisture before drum-off to reduce disposal weight and cost.

- Monitor pH and TSS. Check pH per drum/batch and log results. If neutralization is required, dose in the dewatering stage with agitation and verify before discharge or transport.

- Recycle where viable. Clarified water from dewatering can be returned to the grinder feed in closed-loop setups, provided it’s filtered to prevent abrasive contamination and meets equipment spec.

Integrate edgework. Assign a dedicated edge operator whose evacuation gear is scaled to the edge workload, not pulled from the main crew during “free time.” Edges produce disproportional slurry per square foot due to slower travel speed and increased dwell. Keep their runoff from rejoining main lanes by using small berms and a secondary pick-up.

Finally, communicate with the GC early. Designate staging for drums and equipment, confirm egress routes for waste removal, and plan daily volumes. When slurry handling is mapped, you eliminate bottlenecks that force operators to compromise pass timing—a direct threat to finish quality.

Disposal, compliance, and cost control

Compliance is not optional, and it’s inseparable from cost control. Slurry is high-pH process waste; uncontrolled discharge to soil or storm drains invites fines and damages downstream infrastructure. Build a compliance plan into your estimate, not after mobilization.

Key parameters:

- pH: Most jurisdictions require discharge water between pH 6–9. Achieve this through controlled neutralization during dewatering, not by diluting on the slab.

- TSS (total suspended solids): Local limits vary, but your process water should be filtered to meet discharge or reuse thresholds. Filtration via bags (1–5 micron for polishing stages) or presses reduces TSS and stabilizes downstream chemistry.

- Recordkeeping: Log volumes generated, treatment chemicals used, pH/TSS readings, and disposal manifests. This protects you during closeout and future audits.

Cost levers:

- Source reduction: Meticulous flow control reduces water consumption and downstream handling by 20–40% without slowing production. Train crews to run at the minimum effective flow by grit.

- Onsite dewatering: Filter bags and compact presses lower transport costs by removing water from solids. Dry cake disposal is cheaper and often classed differently from wet slurry.

- Chemical efficiency: Dose neutralizers and flocculants based on measured pH and turbidity, not guesswork. Overtreatment adds cost and can create gelatinous waste that’s harder to handle.

- Reuse: Where allowed, reuse clarified water for coarse grits. This reduces freshwater demand but requires monitoring hardness and fines to avoid tool contamination.

Estimate realistically. For a 20,000 ft² project with mixed hard aggregate, expect 400–800 gallons of slurry water per day under controlled flow, yielding 0.7–1.4 cubic yards of dewatered cake per day, depending on grit sequence and removal targets. Budget handling labor as a parallel crew, not a part-time task: one dedicated tech per grinder keeps production moving and finish quality intact.

Communicate disposal endpoints with your waste hauler. Verify classification, container specs, and pickup schedule before you start. Properly labeled drums with verified pH and solids content ship faster and avoid on-site rework. Above all, tie disposal milestones to your floor milestones—no point hitting shine if your waste is still sitting in the loading bay at walkthrough.

DIAMOND PAD Concrete — Video Guide

A concise demonstration from Ultra Chem Labs walks through using diamond-impregnated pads in tandem with a liquid densifier, highlighting an efficient wet sequence and how the interface should look when slurry is under control. You’ll see the timing of water application, how the pad tracks when it’s in the cut, and when to evacuate versus continue the pass.

Video source: DIAMOND PAD Concrete Polishing by Ultra Chem Labs

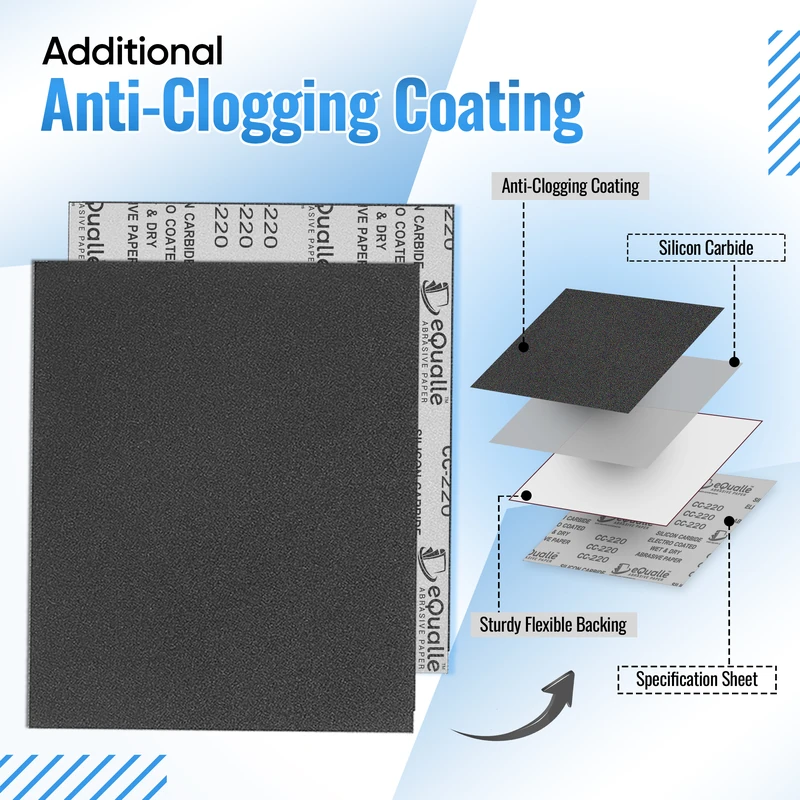

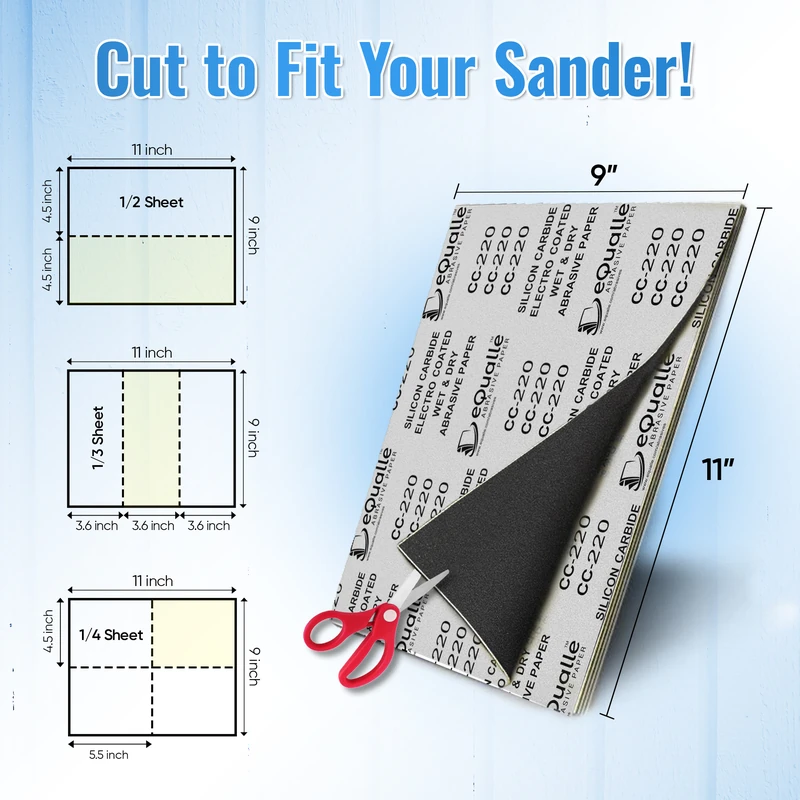

800 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (25-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Ultra-fine grit for pre-polish refinement on paint, clear coats, or resin. Smooths imperfections without damaging the base layer. Provides optimal control when used wet or dry before 1000 or 1200 grits. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: How much water should I run during the opening metal cuts?

A: Start at 0.2–0.4 L/min per head on dense slabs and adjust until the slurry film remains thin, continuous, and easily squeegeed with no pooling two passes behind the grinder.

Q: Does slurry pH affect densifier performance?

A: Yes. High pH and residual fines can impede penetration and reaction. Evacuate slurry thoroughly, lightly rinse, and allow surface moisture to flash before applying densifier per manufacturer timing.

Q: Can I reuse filtered process water for later grits?

A: Often, yes—if it’s filtered to remove fines and verified within equipment specs. Avoid reuse on resin stages where even trace fines can scratch or smear the finish.

Q: What’s the fastest way to fix glazing mid-run?

A: Pause the pass, evacuate slurry, dress the metal segments, reduce flow slightly, and resume with restored pressure/speed balance. Don’t compensate with more water or downforce alone.

Q: How do I estimate drum needs for a multi-day job?

A: For controlled-flow wet grinding, plan roughly one 55-gallon drum of dewatered cake per 10,000–15,000 ft² per day, adjusting for substrate softness, removal depth, and grit count.