Hand Sanding Curves: Wrap Paper Around Dowels

I remember the first time a curve made me question my craft. It was a walnut keepsake box with a lid that looked perfect on CAD: a soft 10 mm radius running cleanly along all four edges. On the bench, though, the radius fought back. My block sander flattened the apex, my random-orbit sander skated off the edge, and every “shortcut” I tried left flats and chatter marks that showed up under finish like neon. I finally reached for the simplest tool in the shop: a hardwood dowel, a strip of abrasive, and my hands. With careful hand sanding—wrapping the paper around a dowel that matched the profile—the radius began to read as a continuous curve instead of a sequence of mistakes. The tactile feedback told me where the high spots were; the scratch pattern told me when I was pushing too hard.

If you’ve ever shaped a guitar neck, a chair spindle, a carved bowl’s rim, or a jewelry bezel, you know this moment. Curves are honest. They reveal your technique, the abrasive’s behavior, and the wood or metal’s grain structure in a way flat surfaces don’t. Machines are great until they aren’t. For small radii, inside coves, or compound curves, a dowel-wrapped abrasive outperforms because it conforms while preserving control.

As a product engineer and reviewer, I’ve tested abrasives across woods (maple, walnut, ash), non-ferrous metals (brass, aluminum), and plastics (acrylic). What consistently works for curved edges is a simple system: pick the right dowel diameter, choose an abrasive that cuts cleanly without loading, and apply repeatable strokes. Below I’ll detail the mechanics—material science, grit sequences, backing choices, and jigs—that let you wrap sandpaper around dowels for curved edges with precision and confidence.

Quick Summary: For clean, consistent curves, wrap sandpaper around properly sized dowels, match abrasive type to material, and use controlled, crosshatched strokes with measured pressure.

Choosing the right dowel and abrasive

Curved edges are geometry problems first. The dowel diameter should approximate or slightly undercut the target radius so the abrasive contacts along an arc rather than at a point. For an outside 10 mm radius, a 20 mm diameter dowel provides full wrap; for tighter control and a sharper apex, drop a size so the paper’s thickness and compressibility make up the difference. For an inside curve (cove), use the exact diameter to prevent faceting.

- Dowel material: Dense hardwood (maple, birch) resists flattening and provides crisp feedback. Softwood compresses and can round over when pressure spikes. For metals or plastics, a hardwood or engineered dowel (e.g., phenolic rod) keeps the radius true under load. PVC pipe works in a pinch for large radii; add a thin cork or rubber layer to introduce controlled compliance.

- Surface preparation: Lightly chamfer the dowel edges to avoid cutting the paper. If you want a “hard” shoe, seal the dowel with shellac or thin CA glue; for a “softer” shoe, wrap a layer of 1 mm cork before the abrasive.

- Paper width: Rip strips slightly wider than the curve so you can pinch the tails for tension. Overlap by 10–15 mm to keep the abrasive tight without a bulky seam.

Abrasive choice is where material science buys you time. Aluminum oxide (Al2O3) is the generalist: tough, micro-fractures slowly, and is ideal for hardwoods and mild steel. Silicon carbide (SiC) cuts faster and sharper—excellent for non-ferrous metals, plastics, and finishes between coats—though it dulls sooner on hardwoods. Ceramic alumina excels when pressure is high and substrates are hard; it maintains its cut rate because of controlled micro-fracturing. Garnet, often seen in woodworking, breaks down to a fine polish on softer woods but loads quickly.

Look at backing and coating:

- Backing: Paper A/C weights are flexible and good for tight wraps; heavier D/F weights or J-flex cloth hold up when you crank tension. Film-backed abrasives (polyester) deliver the most uniform scratch for plastics and metals.

- Coating: Open-coat sheds dust and resists loading on woods; closed-coat gives more points of contact for metals and uniform scratch in fine grits. Stearate (anti-clog) layers are worth it for resinous woods and between-finish sanding.

Your goal for curved edges is a “compliant but controlled” interface: a dowel hard enough to preserve geometry, and an abrasive that cuts without smearing or clogging.

Dialing in hand sanding for curves

When you wrap sandpaper around dowels for curved edges, hand sanding turns into a precision operation. The variables are pressure, stroke, and clocking—the way you rotate the dowel as you move to refresh the abrasive and even out wear.

Technique matters:

- Pressure: Light to moderate pressure maintains radius fidelity. Excess pressure collapses soft backings and rounds edges. Think 0.5–1.5 kgf applied through your forearms, not your wrists. If your scratch pattern looks uneven, you’re pressing too hard or staying in one spot.

- Stroke: Use long, overlapping strokes that follow the curve. For outside radii, sweep around the crest with a rolling motion; for inside coves, stay tangent to avoid digging into the shoulders. Crosshatch by 10–15 degrees between grit steps so you can read when previous scratches are gone.

- Clocking: Rotate the dowel a few degrees every 5–10 strokes to present fresh abrasive. This keeps cut rate consistent and reduces heat and loading.

- Grain direction: On wood, finish with strokes along the grain line to minimize visible scratches. On metals, final strokes should align with the visual lines of the part (e.g., along a bezel edge), then switch to a uniform finishing sequence (e.g., Scotch-Brite or micro-abrasive film).

According to a article, jewelers frequently wrap abrasives around dowels, half-round files, or paint sticks to control tiny radii that rotary tools can’t reach without chatter or overcutting. That same logic applies to woodworking: tactile feedback and direct pressure let you detect high spots instantly.

Common pitfalls and fixes:

- Faceting: If flats appear, your dowel diameter is too small or your stroke is segmented. Step up a size or increase stroke length, keeping the dowel tangent to the radius.

- Over-rounding: If the apex loses definition, your backing is too soft or pressure too high. Switch to a sealed hardwood dowel and reduce pressure.

- Loading: If dust cakes in seconds, you need open-coat or stearated abrasives and better dust extraction. A quick rap on the bench or a rubber cleaning block extends life. For metals, a drop of light oil or soapy water (if safe) reduces loading.

Hand sanding is not about speed; it’s about leaving no trace of how you got there. Practice on a sample offcut with penciled crosshatch. When the graphite disappears uniformly at a given grit, you’ve hit the curve.

Grit progression and surface metrics

A clean curve comes from a disciplined grit progression. Skipping grits saves minutes and costs hours if scratches telegraph through finish. Start with the coarsest grit that removes machine marks without trenching the curve, and step through logical increments.

Typical sequences:

- Hardwood outside radii: 120 → 150 → 180 → 220 → 320. If you plan a film finish, consider 400–600 for a silky burnish; be mindful that overburnishing can affect stain uptake.

- Softwood or resinous woods: 150 → 180 → 220 → 320. Use open-coat stearated papers to avoid clogging that creates random deep scratches.

- Non-ferrous metals: 220 → 320 → 400 → 600 → 800 → 1000 (film-backed). Follow with non-woven abrasive for a uniform satin or move to polishing compounds if desired.

- Plastics (acrylic): 400 (wet) → 600 → 800 → 1000 → 1500 → 2000, then plastic polish. Always wet sand to avoid heat-induced crazing.

Surface metrics help set targets. For wood, visual clarity under finish matters more than absolute Ra, but as a rough guide: an Ra of 3–5 µm (P180–P220) is typical before film finishes; P320–P400 reduces raised grain and improves topcoat flow. For metals, an Ra of 0.4–0.8 µm (approx. P600–P800 film) gives a consistent brushed look; polishing drops that below 0.2 µm.

Wet vs dry:

- Wet sanding on metals and plastics keeps temperatures down and promotes finer scratch patterns. Use water with a drop of dish soap or light mineral oil depending on material compatibility. Avoid water on carbon steel unless you can dry and oil immediately.

- Dry sanding on woods lets you read the grain and scratch pattern better. Dust extraction (a hose or downdraft table) keeps abrasive cutting edges clear and reduces heat.

Change abrasives as soon as cut rate drops. A fresh P220 will remove P180 scratches faster and with less pressure than a “dead” P180. That’s the paradox of sanding: sharpening the tool (new paper) is usually faster than pushing harder.

Fixtures, jigs, and repeatability

Curves on a single piece are one thing; curves across a set—ten chair rungs, four drawer fronts—demand repeatability. Simple jigs keep your “hand feel” consistent from part to part.

Try these fixtures:

- Radius shoes: Make a small library of dowel-backed “shoes” labeled by diameter and grit. A hardwood handle epoxied perpendicular to the dowel improves control and reduces wrist fatigue.

- Depth stop fences: Clamp a scrap with a square edge adjacent to the work so your dowel stops at the same shoulder each time. This prevents over-sanding edges or rolling into adjacent planes.

- Pencil witness lines: Draw parallel lines along the curve. Sand until they fade uniformly to reveal high spots and confirm full contact.

- Profile gauges: Use a contour gauge or 3D-printed template to check your radius. A quick light pass shows contact points; adjust dowel size or pressure accordingly.

- Dust control: A small hose zip-tied near the work (or a DIY downdraft box) keeps the scratch pattern honest by minimizing clogging and slurry.

Four actionable tips for better curved-edge results:

- Pre-shape with a cutting tool: Plane, scrape, or rasp to within ~0.5 mm of your target radius before sanding. Abrasives are for refinement, not hogging.

- Mask no-go zones: Blue tape along adjacent flats acts as a visual border and light abrasion guard so you don’t wash out crisp transitions.

- Stagger seams: If your abrasive strip must overlap, position the seam away from the apex and clock it periodically so it doesn’t track a groove into the curve.

- Use a sacrificial test piece: Keep a sample with the same grain orientation and species next to your work. Run each grit there first to confirm scratch uniformity before touching the real piece.

A good jig doesn’t eliminate craftsmanship; it channels it. With dowel shoes, depth stops, and a repeatable stroke, the curve you dial in on part one is the curve that shows up on part ten.

Materials science of abrasives

Why does one abrasive “feel” right on a curve while another skates or loads? The answer lives in mineral hardness, friability, coating density, and the backing’s compliance.

- Mineral hardness and friability: Aluminum oxide is tough and micro-fractures slowly, maintaining cutting edges under moderate pressure—good for hardwoods that can fracture brittle grains (e.g., oak’s latewood). Silicon carbide is harder and sharper but more brittle; it excels at cutting softer, gummy materials (e.g., aluminum) and at refining scratch patterns at fine grits. Ceramic alumina is engineered to micro-fracture under load, constantly exposing new sharp edges—ideal for high-pressure contact on hard substrates or when you want cut rate to remain stable across long strokes.

- Coating weight and pattern: Closed-coat means the surface is nearly fully covered in abrasive; the cut is aggressive and uniform but can load faster on woods. Open-coat leaves gaps to carry dust away—less loading and better on resinous woods or when sanding between finish coats. Electrostatic grain orientation (common in quality papers) stands sharp edges up for a more efficient cut.

- Binders and stearates: Modern synthetic resins resist heat better than older glue-bond papers. A zinc stearate topcoat reduces loading by creating a dry lubricant layer; this is particularly effective on pine, cherry, and maple where pitch or oils smear.

- Backing behavior: Paper backings flex around tight radii, but their fibers compact under repeated high pressure and can crease. Cloth backings (J-flex) combine flexibility with tear resistance; they’re great for dowel wraps that need high tension. Film backings don’t stretch or swell with moisture and deliver extremely consistent scratch—preferred for metals and plastics on curves because the scratch signature is predictable.

Edge rounding is a function of backing compliance and operator pressure. On curves, a slightly stiffer backing (sealed hardwood dowel + paper D weight or film) preserves geometry. If you need the abrasive to conform more intimately (complex concave shapes), introduce a thin cork layer and lighten your hand to avoid washing out the profile.

One last note: temperature. Friction heat can soften resins, smear plastics, and cook pitch to your paper. If the work feels warm, reduce pressure, increase stroke length, or switch to wet sanding where appropriate. Fresh abrasive is cooler abrasive.

Hand Sanding Basics — Video Guide

Gator Finishing’s “Hand Sanding Basics” offers a concise walk-through of foundational techniques that translate directly to dowel-wrapped work. It covers choosing the right grit for the job, keeping pressure consistent, and how to read the scratch pattern so you know when to advance to the next grit.

Video source: Hand Sanding Basics

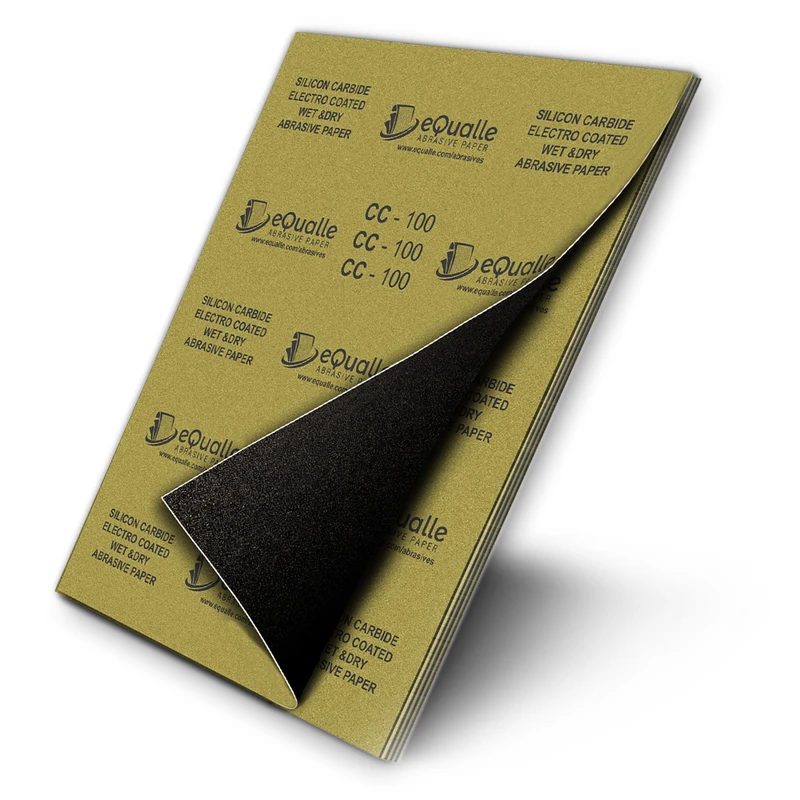

240 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (25-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Smooth-cut abrasive for soft blending, de-nibbing, and light surface preparation before polishing or coating. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What dowel diameter should I use for a 10 mm outside radius?

A: Start with a 20 mm diameter hardwood dowel so the abrasive wraps around and contacts along the full arc. If the apex softens, try an 18 mm dowel or a harder backing to maintain definition.

Q: Which grit should I start with to remove machine marks on curves?

A: Use the coarsest grit that doesn’t trench the curve—typically P120–P150 on hardwood, P150–P180 on softwood, and P220 on metals. Then step through logical increments (e.g., 120→150→180→220→320).

Q: How do I avoid flat spots when sanding an inside cove?

A: Match the dowel diameter to the cove radius, keep long, tangent strokes, and rotate (clock) the dowel to refresh the abrasive. A depth stop fence and pencil witness lines help maintain consistent contact.

Q: Can I wet sand curves, and when should I?

A: Yes. Wet sanding is ideal for metals and plastics to control heat and refine the scratch. Use water with a drop of detergent or a light oil. Avoid wet sanding on steel unless you can dry and protect it immediately; on wood, dry sanding usually reads the grain better.

Q: What’s the best abrasive type for curved edges in hardwood?

A: Aluminum oxide papers are the most reliable general choice. For heavy stock removal or hard exotics, ceramic alumina maintains cut under pressure. Use open-coat, stearated options on resinous woods to reduce loading.