Plastic Oxidation Removal: Coating vs. Surface Oxide

Saturday morning in the shop, coffee ring on the bench, you wipe a thumb across a chalky ATV fender and it ghosts your finger white. Ten feet away, the headlight lens on your daily driver looks foggy and amber; a quick pass with glass cleaner does nothing. On a trailer, the kayak’s once-deep orange now reads as flat and pinkish. If you’ve been hunting for plastic oxidation removal tips, you’re halfway there—but here’s the catch: not all dull plastic is just oxidation. Sometimes you’re seeing degradation of a hard factory coating, and sometimes it’s a thin film of chalk oxidized from the base material itself. Treat them the same and you’ll either stop too early—leaving haze—or go too far—burning through a protective layer you actually needed.

I’ve seen pros waste hours trying to polish a failing clear layer that actually needed removal and recoating. I’ve also watched weekend warriors sand aggressively when a quick chemical clean and a light refine would have popped the original color back in minutes. Knowing which is which dictates everything—your grit choice, your pad, your product, your pressure, even whether you power tool or stick with hand work. We’ll get you to a confident verdict with field tests you can run in minutes, then dial in a plan that respects the material and lands the finish.

We’ll work with what you’ve got: shop towels, painter’s tape, a few solvents, a small stack of sandpaper, and a decent compound. By the end, you’ll be reading the surface like a book and tuning your workflow so you don’t remove what you can’t replace.

Quick Summary: Learn fast tests to identify factory hard coatings vs. simple surface oxidation, then restore each correctly with precise sanding, polishing, and protection.

Clearcoat or Chalk? Field Tests

Before reaching for the sander, run a few simple diagnostics to identify if you’re dealing with a hard factory coating (like a headlight UV hardcoat or automotive clear on plastic trim) or just surface oxidation.

Tape-pull edge test: Mask a hard line on a boundary—edge of a lens, trim seam, or emblem ridge—using painter’s tape. Polish or lightly abrade up to the tape, then pull it off sharply. If you see flaking at the edge or a defined “step” where material peeled, you’re likely disturbing a separate coating. Oxidation alone won’t usually shear in sheets.

Rub and inspect residue: Rub a pea of light compound by hand on a small area with a microfiber. If the residue loads white and chalky while the panel color brightens uniformly, you’re removing oxidation. If residue shows translucent “crumbs” or you expose a different texture underneath, it’s a coating failing.

Visual cue—crazing and ambering: Polycarbonate headlights with a UV hardcoat often develop fine crackle (crazing) and amber tint. That pattern is a hallmark of coating breakdown, not simple surface chalk.

Fingernail “lip” at edges: Trace the edge of a lens or trim with a clean fingernail. If you feel a slight lip—like clear nail polish on top of a surface—that’s a separate coating. Bare, oxidized plastic transitions softly with no step.

Water behavior: Not definitive but useful context. Oxidized plastic tends to soak water and dries blotchy. Intact coatings bead more, fail in patches, and show glossy islands amid dull zones.

Caution with solvents: A hidden-spot wipe with isopropyl alcohol (IPA) should not smear intact hardcoats; acetone will attack bare plastic and many coatings. If acetone immediately “melts” the surface, stop—that’s likely bare plastic or a compromised clear. Use solvents only as a light probe, and only in inconspicuous spots.

If two or more tests point to a distinct layer that’s lifting, plan for controlled removal and recoating. If everything reads chalk with no edge failures or lip, you’re in oxidation territory—good news for a quicker, gentler fix.

Dial in plastic oxidation removal safely

Once you know it’s simple oxidation, your goal is to level off the friable top layer and refine to clarity—without thinning the part. Keep heat low and control your cut.

Step-by-step for oxidized plastic (no intact hardcoat):

- Decontaminate: Wash with a strong but plastic-safe cleaner. Agitate seams with a soft brush to lift embedded chalk. Rinse thoroughly.

- Test a light abrasive: Start with a non-aggressive option—gray Scotch-Brite or 3000-grit foam disc by hand with water. Work a 6x6 inch area, cross-hatched, 8–10 light passes.

- Evaluate: The surface should even out to a uniform matte with the original hue looking saturated when wet. No deep scratches should appear.

- Compound: Use a medium cut compound on a foam cutting pad at low-to-medium speed. Minimal pressure; let the abrasive do the work. Wipe and check often.

- Finish polish: Swap to a polishing pad and refine until clarity returns. If the part is textured trim, skip high gloss and aim for an even, satin uniformity.

Actionable tips:

- Keep a spray bottle of water with a dash of dish soap to wet-sand evenly; it loads the paper less and prevents hot spots.

- Use a soft foam interface pad for curves; a hard block on flat panels to avoid waves.

- If color smears onto your towel (for dyed plastics), your cut is too aggressive—back off to finer grit and shorter cycles.

- When in doubt, expand step 2; most amateurs under-sand fine and over-polish. A flatter, finer scratch base polishes faster and cooler.

For gelcoated fiberglass (kayaks, boat parts), oxidation behaves similarly but the “plastic” is actually a resin layer. Gentle wet sanding followed by a marine compound and polish works well. Avoid cutting through to fiber; monitor color depth and stop if you see fibrous texture.

Headlights, Trim, and Gelcoat: Material Clues

Different parts age differently. Recognizing the material saves time and risk.

Headlights (polycarbonate with UV hardcoat):

- Symptoms: Ambering, spider-web micro cracks (crazing), peeling in patches starting at edges, hazy but still hard to the touch.

- Approach: Plan to remove the failed hardcoat uniformly. Start around 600–800 grit wet if the coating is tough; step through 1000–1500–2000–3000, then polish. You’ll need to reapply a UV-stable topcoat—wipe-on urethane, spray clear (with appropriate safety), or a dedicated headlight coating. Polishing alone won’t hold; uncoated polycarbonate re-oxidizes fast.

Textured exterior trim (PP, TPO, ABS):

- Symptoms: Chalky whitening, color fade, no distinct lip at edges, residue rubs off like talc.

- Approach: Avoid aggressive sanding; you’ll flatten texture. Clean, then use a light gray scuff pad with plastic restorer or a trim-specific coating. Heat guns can “oil out” temporarily but risk warping—use minimal heat only for final touch if necessary.

Painted plastic bumpers and mirror caps (with automotive clear):

- Symptoms: Clear coat peeling like sunburn, edges flake under tape pull, base color dull or exposed.

- Approach: That’s coating failure. Feather sand the edges, remove the failing clear, and plan on repaint with 2K clear or a professional respray. Spot polishing won’t fix flaking clear.

- Note: If you only see haze without peeling and residue is chalky, you might be oxidized clear; in that case, you can polish and protect.

Gelcoat on fiberglass (boats, kayaks):

- Symptoms: Uniform chalking, color looks revived when wet, no flaking edges.

- Approach: Wet sand progressively, compound with a wool pad, then polish and seal with a marine wax or ceramic designed for gelcoat.

In borderline cases, combine tests: if a headlight shows ambering plus a detectable edge lip, treat it as coating failure even if some areas polish clear. Consistency is key; patchy removal leads to halos. And remember: textured trim and soft elastomers don’t want heavy abrasives—clean and restore, don’t chase a gloss that was never there.

According to a article, once a clear coat is visibly flaking, sanding and repainting becomes the reliable fix—polish can’t re-bond what’s already detached.

Sanding Choices: Grits, Blocks, and Tactics

Your grit ladder and tooling choice are your insurance policy. Choose the least aggressive path that still cuts uniformly.

Grit selection:

- Oxidation only: Start 1500–2000 if the chalk wipes easily; jump to 3000 foam, then compound.

- Tough oxidation or orange-peel-like chalk: Begin at 1000–1500, refine to 2000–3000 before polishing.

- Failed hardcoat (headlights): 600–800 to break the top, then 1000–1500–2000–3000.

Blocks and backing:

- Hard block for flat panels (gelcoat hatches, flat trim): keeps surfaces true and avoids waves.

- Soft foam interface on curves (headlights, contoured fenders): maintains even pressure without cutting ridges.

- Fingers only for tight recesses; avoid fingertip “ditching” on open areas.

Technique:

- Cross-hatch passes: 8–12 strokes in one direction, then 8–12 at 90 degrees. Move on when the previous scratch pattern is fully replaced.

- Flood the surface: Keep a steady spray; a soaked surface reduces loading and shows true scratch pattern.

- Minimal pressure: Let the grit work. If nothing is happening, it’s not more pressure—it’s the wrong grit.

- Inspect under raking light: A handheld LED at a low angle reveals remaining deeper scratches and halos.

Safety and control:

- Mask adjacent paint and rubber—grit will scuff instantly.

- Keep edges cool: Lift pressure at edges and creases; they burn through first.

- Clean between steps: Wipe, rinse, and change water when it looks like milk; contaminated slurry adds surprise scratches.

Finish is built in the sanding stage. Don’t expect polish to erase 800-grit valleys quickly; refine your sanding to make polishing a glide, not a grind.

Polish, Protect, and Prevent Next Time

Once you’ve leveled and refined, your polishing strategy and protection determine how long the result lasts.

Polishing workflow:

- Compound: Wool pad on a rotary for gelcoat or heavy defects; foam cutting pad on a dual-action for plastics and headlights to manage heat. Keep the pad flat, 2–3 arm-speed passes, wipe, inspect.

- Polish: Switch to a softer foam with a diminishing abrasive polish. Slow the machine, lighten pressure, and chase clarity rather than cutting.

- Pad hygiene: Spur wool often; clean foam with a brush between sections. A loaded pad mars and heats.

Protection choices:

- Headlights: Apply a UV-stable coating. Wipe-on urethanes offer convenience; 2K clears last longest but require proper PPE and curing conditions. Sealants or waxes alone may give weeks, not months.

- Gelcoat: After polish, a durable marine sealant or ceramic keeps chalk at bay and eases washing. Reapply seasonally.

- Textured trim: A trim coating that penetrates and bonds beats greasy dressings. Look for products with UV absorbers.

Prevention habits:

- Wash with pH-neutral soap; harsh cleaners accelerate oxidation.

- Keep vehicles and gear sheltered or covered when parked long-term.

- Top up protection before peak sun seasons. A quick decon and re-seal takes an afternoon and saves you a full correction later.

If you manage fleet equipment or watercraft, schedule inspections by the calendar, not by “when it looks bad.” Catching the first signs of chalk or ambering means lighter corrections and longer life for coatings and plastics alike.

Buff, Polish and — Video Guide

There’s a helpful walk-through that shows the rhythm of cutting and polishing an oxidized gelcoat surface. The host uses a pro-grade buffer with a wool pad to cut through heavy chalk, then follows with polish and a protective wax—exactly the sequence we’ve outlined, but in motion so you can see pad angle, pressure, and section size.

Video source: Buff, Polish and Wax Your Boat: Gelcoat Oxidation Removal, How to Step by Step

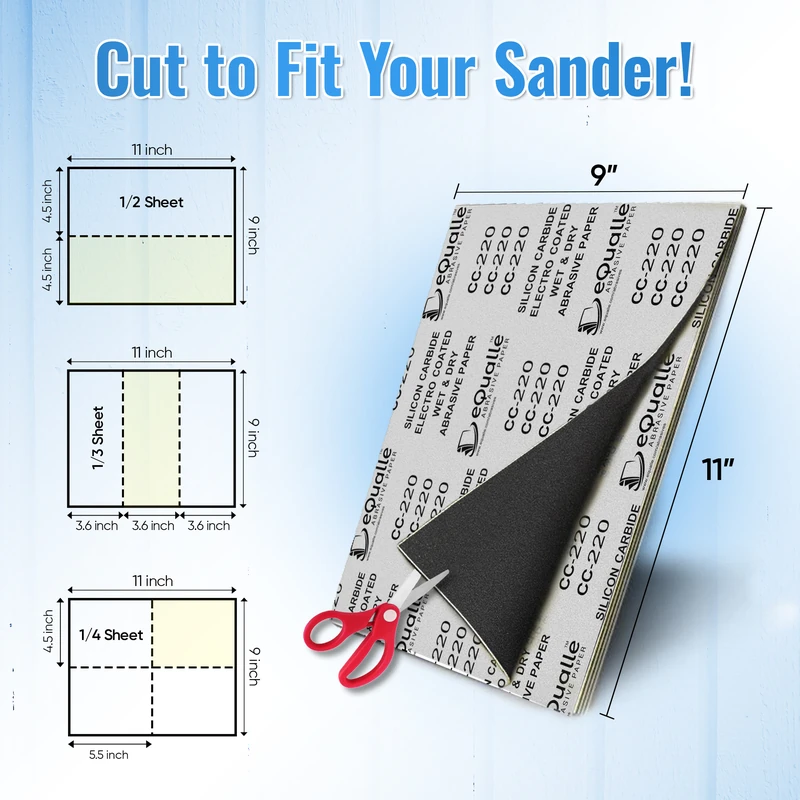

800 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (10-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Ultra-fine grit for pre-polish refinement on paint, clear coats, or resin. Smooths imperfections without damaging the base layer. Provides optimal control when used wet or dry before 1000 or 1200 grits. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: How can I quickly tell if my headlight has a failing hardcoat or just oxidation?

A: Look for amber tint and fine crackle (crazing), plus a slight “lip” at edges. Do a tape-pull at a sanded edge—if material flakes in sheets or you see a distinct step, it’s a hardcoat failing. If residue from a light compound rub is just chalk and the surface evens out without edge lifting, it’s likely simple oxidation.

Q: What grit should I start with for headlights that are badly cloudy?

A: If you’ve confirmed hardcoat failure, start at 600–800 grit wet to break the coating uniformly, then step 1000–1500–2000–3000 before polishing. If there’s no coating and it’s just haze, begin much finer—1500–2000—and refine from there. Always test a small area and escalate only as needed.

Q: Is it safe to use a heat gun on chalky plastic trim to restore color?

A: Minimal heat can temporarily darken some plastics by drawing oils to the surface, but it risks warping, gloss patching, and long-term brittleness. It’s better to clean thoroughly, lightly scuff if appropriate, and apply a dedicated trim coating with UV protection. Save heat only for careful final touch-ups on textured trim, and keep it moving.

Q: Can I just polish oxidized gelcoat without sanding?

A: Light oxidation can often be compounded directly. For heavy chalk that clogs pads instantly or leaves uneven blotches, a quick wet sand at 1000–1500 grit to flatten the surface makes compounding faster, cooler, and more uniform. Always refine to at least 2000–3000 before final polish for the best clarity.

Q: How long will my restoration last after plastic oxidation removal?

A: Longevity depends on protection and exposure. Headlights polished and left uncoated may dull within weeks; a proper UV topcoat can last a year or more. Gelcoat protected with a quality marine sealant can hold gloss for a season. Regular washing, periodic re-sealing, and avoiding harsh cleaners extend results significantly.