Why Detail Sander Sheets Require a Light Touch

It starts with a hum—the compact orbit of a delta-pad gliding toward a tight inside corner where a cabinet door stile meets the rail. The walnut is older than your clamps, with grain that doesn’t forgive. You’ve prepped the shop, dialed down the RPM, and set up extraction, but your fingers still tense as you aim the tip into a fillet. Press too hard, and you’ll carve a shallow dish that daylight will announce the moment a finish hits. If you’ve ever found yourself polishing out a crater that appears only under raking light, you know the culprit: load. The solution isn’t exotic; it’s discipline. Use light pressure to prevent gouging—especially when your abrasive is fresh and your tool is nimble. That’s where the right detail sander sheets make or break the outcome.

Detail sanders are seductive because they reach where larger pads can’t, but that advantage magnifies mistakes. The triangular nose, the foam interface, the small contact patch—all conspire to concentrate force. When the grain transitions, when you cross an edge, when you feather old finish into raw substrate, the sander begs you to lean in. Resist it. Let the grains cut at their designed point load. Choose detail sander sheets with the right grit, backing stiffness, and coating, keep the tool moving, and treat every pass as additive rather than corrective. This mindset extends across substrates—from wood face frames to painted MDF, and even into auto-body spot repairs where the same physics of pressure and heat apply. If you’re after repeatable surface quality, the lightest workable touch is the most powerful habit you can build.

Quick Summary: Gouges and dish-outs come from excess pressure; select the right detail sander sheets, use minimal downforce, and maintain constant motion for predictable, high-quality finishes.

The Physics of Pressure and Gouging

Every scratch you leave is a function of contact pressure (force per unit area), grain sharpness, and motion. With small pads—especially the triangular “delta” form used on detail sanders—the contact area is small, so even modest force translates into high PSI. At the tip, the effective area shrinks further. That’s why leaning into the point leaves crescents and divots that only reveal themselves after finish.

Abrasive grains are engineered to cut and micro-fracture at specific loads. Excess downforce crushes the resin bond, smears swarf, and raises temperature, promoting “loading” (clogging). Once loaded, the sheet stops cutting cleanly and begins burnishing and plowing—classic precursors to gouging. On random-orbit detail sanders, too much pressure also suppresses the orbit, trading shear cutting for stick–slip chatter. The result: pigtails and isolated troughs rather than a uniform scratch field.

Guidelines for downforce help. As a rule of thumb, add no more than 0.5–1.5 lb (0.2–0.7 kg) of hand pressure beyond the tool’s own weight for finish passes. On delicate edges and end grain, the tool’s weight alone is often sufficient. You can calibrate this by practicing on a bathroom scale—press the sander pad onto the scale and learn what one pound feels like through the grip you actually use.

Foam interfaces complicate pressure, too. Compressing the pad defeats its ability to conform to minor undulations. Instead of distributing load over micro-highs, it bridges and localizes force at the first point of resistance—the exact condition that scoops earlywood on softwoods or leaves low spots straddling joint lines. Dust extraction changes the equation as well: efficient vacuum pulls debris away, reduces hydroplaning on swarf, and restores a clean cut at lower pressure. The safest path is consistent: light downforce, constant motion, and frequent inspection under angled light.

Selecting detail sander sheets for control

The sheet you choose dictates how forgiving your passes will be. Detail sander sheets vary in grain type, backing, coating, and hole pattern. Each parameter influences cut aggressiveness, heat, and the margin of error when pressure creeps up.

Grain type:

- Aluminum oxide is the baseline for woods—tough, self-renewing, predictable in grits 80–220.

- Ceramic and ceramic-blend grains cut cooler and faster; use them for initial leveling, but be extra mindful of pressure at the pad tip.

- Silicon carbide excels on finishes, plastics, and non-ferrous metals; its friability yields a finer scratch but demands light touch to avoid streaking soft substrates.

Backing and flexibility:

- C-weight papers flex and conform better, ideal for profiles and molded edges.

- D/E-weight papers are stiffer; they track flatter on faces but can “edge-dig” on curves if you lean.

- Film-backed sheets distribute pressure uniformly and resist edge tear; they’re excellent for final passes and for reducing scratch marks under light downforce.

Coatings:

- Open-coat reduces loading on resinous woods (pine, fir) and when cutting old finishes.

- Stearate top coat further mitigates clogging and heat; it’s almost essential in high-humidity shops or when sanding lacquer.

Hook-and-loop vs. PSA:

- Hook-and-loop (H&L) facilitates frequent sheet changes—a best practice for keeping pressure light while maintaining cut rate.

- PSA gives a firmer feel but punishes misalignment and makes mid-pass swaps less likely; reserve it for controlled, flat work.

Hole patterns matter more than many realize. Aligning the sheet’s extraction holes to the pad is non-negotiable. Misalignment increases heat, clogs grains, and tempts you to push harder to compensate. Opt for sheets whose hole map matches your pad or use multi-hole “universal” patterns that still present open area around the tip.

H3: Choosing grits that forgive For tight corners and edges, don’t start rough unless you must. On hardwoods, 120 or 150 grit with a ceramic or premium aluminum oxide grain often removes mill marks safely at low pressure. Drop to 80 only for true flattening or heavy finish removal, and plan to step through 120 and 150/180 before 220. Each step should erase the prior scratch pattern at the same light downforce; if you find yourself pressing, the grit is wrong or the sheet is spent.

Workflows for curves, edges, and profiles

Curves, chamfers, and profiled moldings amplify pressure mistakes because geometry focuses load. The path to clean results is a workflow that pre-decides motion, grit, and where you’ll never dwell.

Edges and arrises:

- Break sharp edges by hand first with a sanding block at 45 degrees (two or three light passes). This reduces the risk of the pad grabbing and gouging the corner.

- Approach edges with the pad flat, not tipped. Let only the last 3–5 mm of the pad cross the edge, and keep moving.

Inside corners and fillets:

- Use the pad’s tip as a tracing tool, not a chisel. Float the tip in and sweep past the corner; never pivot and grind in place.

- Reduce speed one notch to limit aggressiveness, and decrease downforce to near-zero. Let fresh 150–180 grit sheets do the work.

Curved rails and profiles:

- Introduce an interface pad (thin foam) to increase conformity and distribute force.

- Follow the profile with the whole pad, not just the tip, in overlapping arcs.

According to a article, a light touch and constant motion are especially critical on curved surfaces to avoid flat spots and scallops. That isn’t just stylistic advice—it’s a safeguard against pressure spikes that carve troughs in earlywood or soften crisp reveals on millwork.

Actionable tips for pressure control on profiles:

- Mark high-risk zones (edges, carvings, end grain) with pencil. If the markings disappear unevenly, your pressure or dwell is off—correct immediately.

- Count strokes rather than time. For example, three passes per segment, pad fully supported, then move on.

- Keep a “check light” at the bench. Sweep raking light across the surface each grit; light pressure plus early inspection prevents deep fixes later.

- Use your off-hand as a limiter. Two fingers resting lightly on the work near the pad will remind your lead hand not to bear down.

Abrasive performance and grit progression

Abrasive performance is dynamic; grains micro-fracture to expose new edges, then dull, then load. Reading this curve lets you maintain a light touch without losing cut rate.

Progression strategy:

- Stock removal: 80 → 120 → 150.

- Pre-finish on hardwoods: 150 → 180 → 220.

- Film or high-build finishes: stop at 180 before film coats to promote adhesion; sand between coats with 320–400, light pressure only.

- Plastics and acrylics: 400 → 800 → 1200–2000, using foam backing and ultra-light pressure to prevent heat haze.

Scratch removal windows:

- Each successive grit should remove the prior scratch in 6–10 passes at light pressure. If not, either your passes are too fast, your sheet is loaded, or you skipped too far in grit.

Sheet life and rotation:

- Rotate the sheet orientation periodically to present a fresh edge at the delta tip—this evens wear and reduces the urge to press.

- The moment you feel heat through the pad or see dust turn darker, swap sheets. Loaded abrasives require pressure to cut; that’s the pathway to gouging.

H3: Grain, heat, and substrate interactions Softwoods: Earlywood collapses first under pressure, leaving washboarding along the grain. Use open-coat 120/150, low speed, and a floating pad.

Hardwoods: Dense latewood resists; pushing will undercut earlywood zones. Film-backed 150/180 at low-moderate speed with strong extraction will maintain flatness.

Paint and primers: Stearate-coated 180/220 removes feather edges cleanly; pressing heats the film and causes gummy build-up. If the sheet drags, stop and clean or replace it.

Automotive fillers: Detail sanders can finesse spot putty and primer nibs, but only with film-backed 320–600 and feather-light pressure. Let the sheet glide; otherwise, you’ll undercut the surrounding panel and telegraph lows.

Ergonomics, dust, and finish quality

Pressure control starts with posture and ends with dust. The way you hold the tool determines how easily you can maintain the light touch that prevents gouging.

Grip and stance:

- Choke up just enough to control the nose, but keep your wrist neutral. A bent wrist adds unconscious force.

- Stand so your shoulder aligns with the direction of travel; pushing from the shoulder reduces wrist-driven spikes in pressure.

Hand placement:

- Use three points of contact: the tool grip, your off-hand lightly guiding the front housing, and a finger feathering near—but not on—the pad outline to sense tilt.

- Avoid pinching the tool at the nose; that’s the quickest way to overload the tip on entry.

Tool settings:

- Run one step lower speed for profile work. Lower RPM reduces aggressiveness and heat, allowing light pressure to remain effective.

- Keep extraction strong. A clean interface means you don’t have to compensate by pushing. Check hose drag; a tugging hose makes you lean into the stroke.

Dust as a cutting variable:

- Dust becomes a third body between grain and work. When it cakes, your sheet skates and then bites—classic gouge behavior. Purge the pad with compressed air between sections and vacuum the work surface before each pass.

- If you see “dirty” scratches, you’re cutting with debris. Stop, clean, and resume with the same light pressure.

Actionable calibration routine:

- Practice on a scale: learn the feel of 1 lb of added force through your actual grip and stance.

- Pencil crosshatch, three passes, vacuum, then inspect. If marks remain, change grit—not pressure.

- End every grit with two feather passes at half speed and zero added force to reset any micro-dish.

Milwaukee M12 Orbital — Video Guide

If you’re considering a modern compact detail sander, the Milwaukee M12 FUEL orbital unit is a strong reference point. In a recent shop review, the presenter highlights how the tool’s small footprint and delta pad make it an everyday problem-solver for corners, face frames, and edging. More importantly, the variable speed and well-balanced motor let the abrasive do the work—perfect for maintaining a light touch.

Video source: Milwaukee M12 Orbital Detail Sander is AMAZING!

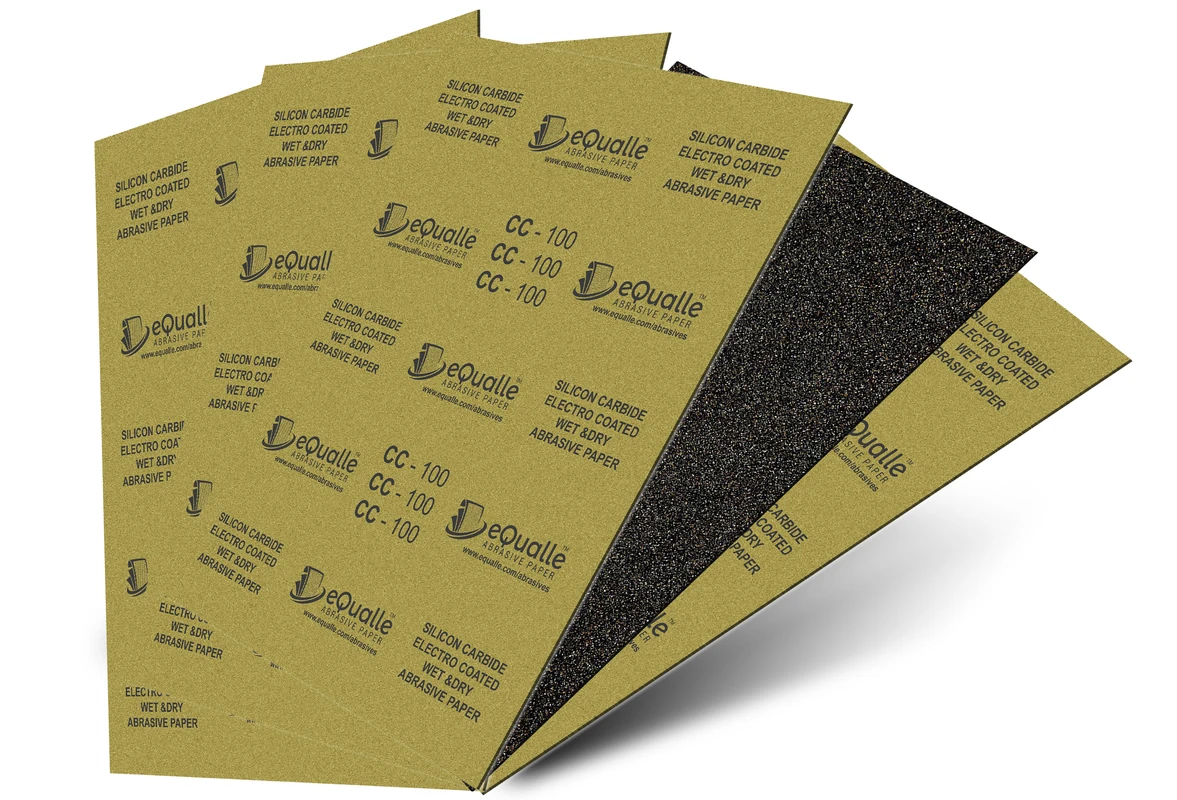

280 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (25-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Fine abrasive for leveling varnish or clear coats with precision. Creates a refined surface before high-gloss finishing. Performs reliably on wood, resin, or painted materials in wet or dry conditions. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: How much pressure should I apply with a detail sander?

A: Add no more than 0.5–1.5 lb beyond the tool’s weight for finish passes. On edges and inside corners, aim for the tool’s weight only and let fresh abrasives cut.

Q: Why do gouges appear near edges and corners?

A: The triangular pad concentrates force at the tip. Any extra pressure spikes PSI, suppresses the orbit, and plows the substrate, especially where support drops off.

Q: What grit progression minimizes risk of gouging on hardwood?

A: Start at 120 or 150 unless heavy defects exist, then move to 150/180 and finish at 220. Use film-backed sheets for final passes and prioritize dust extraction.

Q: How do I prevent pigtails on a detail sander?

A: Keep pressure light, align dust holes, run a clean sheet, and maintain motion. If pigtails appear, stop, clean the pad and surface, and resume at one speed lower.

Q: When should I replace detail sander sheets?

A: Replace when cut rate drops, heat rises, or dust darkens. If you feel drag and are tempted to push harder, the sheet is either loaded or dull—swap immediately.