Straight Edges with a Sanding Block: Engineer’s Guide

There’s a quiet satisfaction when a board’s edge goes from ragged to crisp under your fingertips. You sight down the length, catch a glint of shop light, and see a clean, uninterrupted line—no ripples, no dips, no proud corners snagging a cloth. That straightness is the difference between a door that closes like a whisper and one that bites the jamb. It’s the moment where craft meets physics, and for me—an engineer who lives for process—the right tool is what makes that moment repeatable. For edge work, that tool is a sanding block.

You can flatten and refine edges with machines, but a sanding block gives you tactile feedback and square control machines can’t. When tuned, it acts like a manual surface planer with a micro-adjustable cutting rate: your grit defines the “tooth geometry,” the block’s stiffness controls the contact patch, and your hands meter pressure and stroke geometry. The goal isn’t just smooth—it’s straight and square, with predictable material removal across the full length. In my shop and tests, block control unlocks a level of precision that reduces post-fit headaches. When a drawer side or guitar body blank needs a true edge, I reach for a block, not because it’s slower, but because it’s transparent. Every pass teaches you something about the wood, the abrasive, and the interface between them.

This guide distills what I’ve measured and learned: why edges go wavy under sandpaper, how to pick the right block and abrasive, and exactly how to apply pressure and strokes to keep things straight. We’ll also cover verification—using straightedges and feeler gauges—so your process closes the loop. If you’ve ever sanded an edge that looked good but revealed low spots under finish, this is the control map you’ve been missing.

Quick Summary: Use a stiff, correctly sized block with stable abrasives, maintain even pressure and stroke geometry, and verify flatness with measurement, not guesswork.

Why edges wander under hand sanding

If you’ve ever “sanded a curve into a straight,” it’s not for lack of effort. Three mechanics are usually to blame: localized pressure spikes, a compliant interface, and inconsistent stroke geometry.

Contact pressure (p = force/area) drives removal rate. When your fingers pinch the block, you create pressure nodes that cut faster under your fingertips. Over a dozen strokes, those nodes become micro-coves, and you’ll feel a condition I call edge “softening”—the arris rounds and the length subtly serpents. A more compliant block (soft foam or thin cork) amplifies this effect by wrapping around high spots instead of planing them. That’s great for contour sanding, catastrophic for straight edges.

Stroke geometry is the second culprit. Short, localized strokes build divots—think path-dependent wear. Long, end-to-end strokes average the surface, but off-axis strokes can introduce a bias, especially if you consistently exit the edge at the same angle, rolling pressure over the corner. Finally, abrasive behavior matters: dull grains burnish instead of cut, increasing friction and inviting the user to push harder, which worsens pressure spikes. Fresh abrasives cut cooler and straighter.

Wood anatomy adds a twist. Earlywood vs. latewood and interlocked grain will cut at different rates. Dense latewood bands resist, so your pressure subtly “seeks” earlywood. Without awareness, your edge follows density rather than the line you intended.

The fix starts with system rigidity and distribution: a block long enough to bridge over local errors, a backing that doesn’t sag, and a grip that lets the palm—not fingertips—deliver force through the block’s centerline. Pair that with an end-to-end stroke that spends equal time across the length, and you’ll turn a hand tool into a controlled straightener.

Pick the right sanding block and abrasive

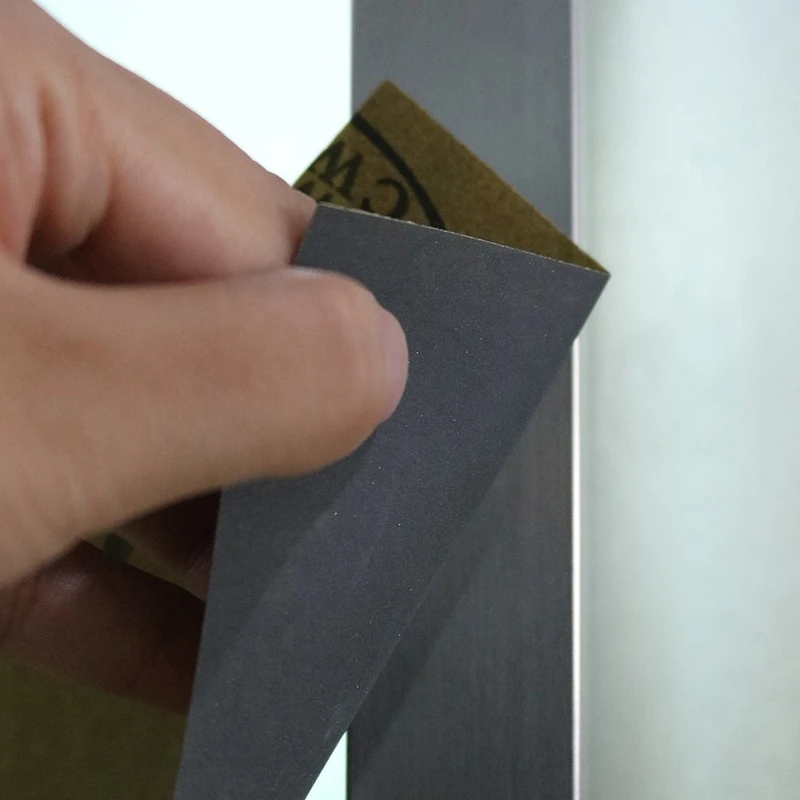

The block is your micro-plane body; its stiffness and size define the contact patch that governs straightness. For edges, choose a block 250–300 mm (10–12 in) long and 60–80 mm (2.5–3 in) wide. That length averages out small deviations, and the width provides stability without being unwieldy. Materials matter: dense cork or medium-durometer rubber (50–70A) balances slight conformity for scratch blending with enough stiffness to avoid edge rounding. Hardwood blocks shine for dead-straight work; just break the edges to avoid printing lines into the workpiece. Avoid ultra-soft foam for edge straightening—it’s for curves.

Abrasive chemistry and backing are the other half. Aluminum oxide sheets are workhorses for wood; ceramic alumina cuts cooler and lasts longer on dense species. Silicon carbide is sharp but fractures fast; it excels for between-coats leveling and resin-rich surfaces. For edge work, I prefer a stearate-coated aluminum oxide for clog resistance. Backing weight (C/D/E) impacts support—heavier backings stay flat on a rigid block. Film-backed abrasives offer incredible uniformity and tear resistance; they’re excellent when you need a predictable scratch pattern.

Attachment matters for consistency. PSA (pressure-sensitive adhesive) minimizes slip and keeps the sheet flat; hook-and-loop adds a soft interface and can introduce compliance, so use it only if you need a hint of forgiveness. Sprayed repositionable adhesive is viable when you want to change grits frequently without residue, but screen the block face for flatness afterward.

Grit progression is less about tradition than control of depth of cut. Start coarse enough to true the edge quickly (80–100 grit), then refine to 120/150 and stop when the surface reads uniformly under raking light. Jumping too fast (e.g., 80 to 220) leaves rogue scratches that trick your eye into chasing phantom low spots. For squareness, pair the block with a reference—your bench top, a fence, or a shooting board—to keep the sanding plane orthogonal to the face.

Master pressure and stroke geometry

Picture the block as a sled distributing a load. You want the load centered, low, and constant. Palms-forward grip, thumbs riding lightly on top, keeps your fingers from acting like little jackhammers. Apply only enough downforce to keep the block engaged; let sharp grit do the cutting. If you feel heat, chatter, or grab, that’s feedback: lighten up, clean the abrasive, or change sheets.

Think in terms of travel distance per region. If 25% of your strokes over-index the last 100 mm of the board, that region will cut faster. Count strokes or use a simple timer: three full-length passes, then flip the board end-for-end and repeat. Symmetry reduces bias. I also mark the edge with a soft pencil in inch-long bands; even removal of the graphite tells you your stroke distribution is balanced.

Stroke angle controls scratch blending and reduces the chance of grooving. Use a shallow skew (10–15°) relative to the edge. It increases effective cutting length and helps the block “plane” rather than scrape. Avoid rolling off the edge—keep the block flat as you exit; imagine rails guiding your wrists straight through. When you need micro-adjustment, hang the block off the high side by 5–10 mm; this reduces contact area over the high spot and increases local pressure in a controlled way. Use sparingly and return to full-width strokes to re-average.

Grit changes are checkpoints. Before moving up, inspect under raking light. The moment you see uniform scratch orientation and no low graphite bands, you’re ready. If you’re fighting stubborn highs and lows, resist the urge to press harder; switch back to a fresh coarse sheet. According to a article, even small changes in block firmness and adhesive choice can meaningfully alter how evenly the paper tracks—worth testing in your own setup.

Measure flatness like a pro

Trusting your eyes is romantic; trusting your instruments is reliable. Verification closes the loop and turns technique into a process you can repeat.

Start with a quality straightedge at least as long as the edge. Place it against the work under a raking light or backlight, and look for light leakage. Quantify those gaps with feeler gauges—if you can slide a 0.05 mm (0.002 in) leaf in anywhere, you’ve got a low spot. Mark it. For squareness, use a machinist’s square: register the beam on the face and check the edge at multiple points along its length. If the edge leans, adjust your grip and consider a fence or shooting board to keep the block orthogonal.

Surface metrology can be simple. A strip of contrasting chalk or graphite wiped across the edge will reveal highs and lows in one pass. After a few strokes, the remaining pigment shows lows; remove the highs until the pigment disappears uniformly. I also use a digital caliper to spot-check thickness near the edge; consistent readings within ±0.1 mm indicate you’re not tapering.

Lighting matters more than you’d think. A low-angled, cool LED will exaggerate scratches so you can see directionality and missed spots. Flip the board 180° under the same light to confirm—you’re looking for consistent reflection.

Finally, set tolerances appropriate to the task. Cabinet doors and boxes generally need ≤0.1 mm variation over 600 mm to avoid perceptible misalignment. For instrument making or high-precision joinery, you may aim for ≤0.05 mm. Don’t chase numbers beyond what the project demands—overworking edges can wash out the arris and create a delicate, damage-prone line.

A repeatable edge-sanding workflow

Consistency comes from a standard workflow. Here’s the sequence I use and teach when I need a dead-straight, square edge.

Prep and reference: Joint or saw the edge reasonably straight. Mark a small triangle across the board face and edge to track orientation. Draw light pencil bands on the edge to visualize removal. Set your bench or a flat fence as the reference plane.

Block and grit setup: Mount 100-grit aluminum oxide on a 300 × 70 mm hardwood or firm rubber block using PSA. Chamfer the block’s edges to prevent printing. Keep 120 and 150 grits ready; any higher is rarely necessary for a working edge.

First truing passes: With the block flat and skewed 10–15°, make 3 full-length strokes. Flip the board end-for-end and repeat. Check your pencil bands. If highs persist, spot-adjust: overhang the block 5 mm on the high side for 2–3 strokes, then return to full-width passes.

Square check and correction: Use a machinist square every 8–10 strokes. If the edge leans, bias pressure toward the high side by shifting your palm 10 mm—not by pressing with a fingertip. Re-check after every correction cycle.

Refine and verify: Move to 120 grit only when the scratch pattern is uniform and your straightedge shows ≤0.05–0.10 mm gaps. Repeat the pass-count routine. Finish at 150. Break the arris with one light pass if the edge will be handled frequently.

Five actionable tips to keep it straight:

- Use longer blocks for straighter edges: 10–12 in beats 6–8 in every time.

- Center your load: palms over the block’s centroid; avoid fingertip pressure.

- Pencil bands are your “cut map”: don’t move up in grit until they disappear evenly.

- Overhang to spot-correct highs, then immediately re-average with full-width strokes.

- Verify with instruments, not intuition: straightedge plus 0.05 mm feeler is a simple, powerful check.

When the sanding block isn’t the answer

Sometimes the fastest path to straight is not more sanding—it’s smarter staging. If your edge is more than 0.5 mm out along its length, start at the jointer or use a hand plane to reset the baseline. A sanding block shines for refining and sneaking up on square, but it’s a slow stock-removal tool.

Consider material and finish. Oily exotics can clog abrasives quickly; use open-coat papers and clean the sheet frequently with a crepe block. Resinous softwoods load even faster; stearate-coated abrasives cut longer with less heat. For edges that will be finished clear, stop sanding before the wood loses crispness; a lightly broken arris holds finish better and looks sharper than a fully rounded one.

Also think ergonomics. If your workpiece is short, clamp it high enough that your forearms are parallel to the bench—this keeps your force vector normal to the edge and reduces the tendency to roll. For very long edges, a deadman or auxiliary support prevents deflection that can trick you into over-cutting.

Last, plan the sequence with the final assembly in mind. If two edges will be joined, treat them as a pair: clamp them together and sand as one to maintain mirror symmetry. Label the orientation so you don’t swap edges later. A few minutes of planning can save you an hour of chasing invisible misalignments after glue-up.

Beginner Sanding Mistakes — Video Guide

If sanding feels simple but your results vary, this short video on beginner sanding mistakes is a smart primer. It’s a clear walkthrough of how pressure, grit choice, and stroke habits affect the surface—and why “just sand more” often backfires. The presenter demystifies the dull parts: why to start coarser than you think, how to keep the block flat, and when to stop.

Video source: Beginner Sanding Mistakes | How to Sand

280 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (50-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Fine finishing grit for delicate work—ideal for flattening varnish layers and creating a pre-polish smoothness on wood or resin. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What block material gives the straightest edges

A: A stiff hardwood or medium-durometer rubber (50–70A) on a flat face plate keeps the contact patch planar. Avoid soft foams that wrap around edges and cause rounding.

Q: Which grit sequence should I use for edge straightening

A: Start at 80–100 to true, then 120 and 150 to refine. Only move up when scratches are uniform and gaps under a straightedge are ≤0.1 mm. Going higher rarely improves straightness.

Q: How do I keep the edge square to the face

A: Use a reference surface and check with a machinist square every few passes. If it leans, shift your palm 10 mm toward the high side and take 2–3 corrective strokes before re-averaging.

Q: PSA, hook-and-loop, or spray adhesive for the paper

A: PSA provides the flattest interface for straight edges. Hook-and-loop adds compliance and can round. Repositionable spray works if you need frequent grit changes; just verify block flatness.

Q: How much straightness is “good enough” for furniture

A: As a practical target, hold variation to ≤0.1 mm over 600 mm for casework. For high-precision joinery or instruments, aim for ≤0.05 mm. Set tolerances to the project’s needs.