When to Drop Back Sandpaper Grit to Fix Defects

Saturday morning. Coffee cooling on the bench, raking light cutting across your project like a truth serum. You wanted a quick scuff-and-recoat—thirty minutes, tops. Instead, the panel keeps whispering back at you: that line near the edge, the mysterious dull patch that won’t clear, the faint spiral that appears only at a certain angle. You switch sheets, then pressure, then motion, but the micro-scratches stubbornly telegraph through. It’s the universal moment where your patience meets physics: do you keep climbing up the sequence or drop back a sandpaper grit to reset the scratch pattern?

I’ve been there in labs and garages—measuring scratch depths with a loupe and checking gloss at 60 degrees, tallying how many passes it takes different abrasives to remove a witness line. I’ve run controlled A/Bs on aluminum oxide vs silicon carbide, paper vs film, open-coat vs closed-coat, dry vs wet. The tricky part is less about “what grit is best” and more about “when do you change direction.” The wrong decision can cost time and thickness. The right decision protects your finish and your schedule.

In this guide, I’ll keep it practical. You’ll get decision rules grounded in material science and field testing, not folklore. You’ll learn what the surface is telling you—how to read scratch geometry, load patterns, and defect persistence—and exactly when it’s time to drop back a grit without starting over. Whether you’re flattening a maple tabletop, knocking down nibs in polyurethane, or chasing dust in automotive clear, the same physics apply, and the same evidence-based checkpoints will keep you on track with the right sandpaper grit at the right moment.

Quick Summary: Drop back a grit when a defect survives two disciplined cycles at the current grade, or when the defect height exceeds your safe removal budget at that grade.

Detecting Defects Early

Most “too-late” drop-backs begin with poor detection. If you see a defect only after jumping two grits higher, you’ve already spent thickness and time with scratches that won’t help. Start with three controls: light, guide, and clean.

- Light: Use raking light at a low angle; a bright LED bar or even a flashlight works. For glossy films, add cross-lighting—one low, one high—to catch both deep scratches and fine swirls. For wood, low-angle light reveals planer tracks, torn grain, and low spots.

- Guide: On films and metal, use a dry-erase marker or aerosol guide coat misted across the surface. On wood, a soft pencil scribble pattern is enough. The guide disappears only where you’ve made contact; any persistent marks flag lows or sheltered defects.

- Clean: Between checks, remove swarf. Dust compacts in valleys and fakes “fill.” Wipe with a clean microfiber; for wet sanding, squeegee water off and inspect while the surface is still damp (the “wet reveal” enhances contrast).

Test for defect persistence early. Sand a 10 cm x 10 cm patch with consistent pressure and pattern (e.g., eight crosshatch passes). If the defect stays visible or your guide coat remains in a local zone after that controlled cycle, mark it. That’s your evidence point for whether to drop back. Randomly scrubbing yields noise; controlled cycles yield data.

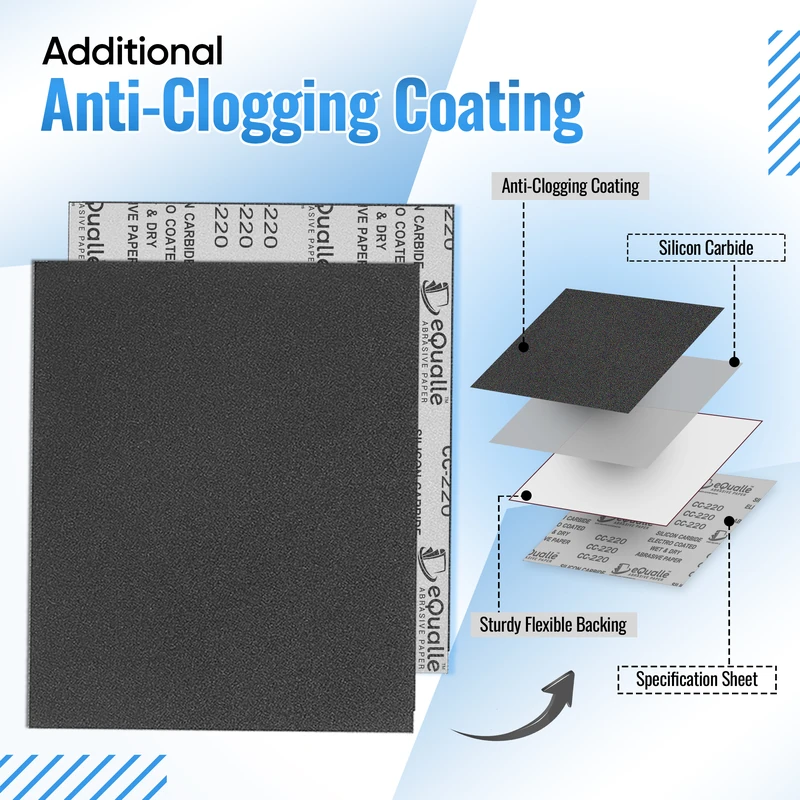

Finally, read granule behavior. If your abrasive loads prematurely or sheds unevenly, your scratch pattern will be chaotic, and defect removal will be inconsistent. Open-coat aluminum oxide excels on resinous woods; silicon carbide with water outperforms on hard films because it fractures and refreshes its cut. Film-backed discs give a tighter scratch distribution than paper, making defect detection more honest. Consistent scratch geometry is the foundation for smart grit decisions.

How sandpaper grit maps to scratch depth

To decide when to drop back, you need an intuitive map between sandpaper grit and the scratches it creates. Grit ratings describe abrasive particle size distribution, but the scratch you see is a function of particle size, hardness, backing, coat density, pressure, and lubricant.

- Scale matters: FEPA “P” grades (P320, P800) aren’t directly identical to CAMI (320, 800). Stick to one system per job. FEPA P320 is roughly 46 µm average particle size; P800 is ~21 µm. Scratch depth is typically a fraction of particle size—often around 1/5 to 1/10 in rigid films—depending on pressure and backing.

- Backing and coat: Film-backed abrasives maintain flatness, keeping peaks cutting evenly. Paper can dish slightly and vary scratch depth. Closed-coat papers (more grit coverage) cut faster but may load on soft substrates; open-coat reduces loading, making scratch depth more consistent on gummy materials.

- Abrasive mineral: Silicon carbide fractures into sharp micro-edges and produces a narrower, shallower scratch field as it wears—good for finishes, stone, and glass. Aluminum oxide is tougher and more forgiving on wood. Ceramic alumina and seeded gel excel on metals, maintaining cut under pressure but can cut deeper if you lean too hard.

In practice, each step up should reduce scratch spacing by ~30–40% and depth by roughly half. Jumping too far (e.g., P120 to P320 on hardwood, or P800 to P2000 on clear coat) invites ghost scratches that won’t resolve with the fine grade. Conversely, staying too coarse for too long wastes thickness and leaves deep grooves that demand significant removal later.

A rule of thumb:

- Wood stock prep: P80 → P120 → P150/180 → P220. Each jump ≤1.6x in particle size ratio.

- Film finishing: P800 → P1200 → P1500 → P2000/2500. Avoid skipping more than one step unless your prior scratch is perfectly uniform and shallow.

- Resin polish: P400 → P800 → P1200 → P2000 → compound. For large defects, drop to P320/400, but only if your thickness budget allows.

The key: if your current grit won’t clear the previous grit’s scratch in two disciplined cycles, that’s a diagnostic flag. Don’t keep climbing. Drop one step back to re-establish a uniform scratch field you know the next grit can fully erase.

Decision rules: drop back or push forward

Defects fall into two groups: shallow surface flaws (nibs, dust, light orange peel) and deeper geometry issues (sags, runs, low spots, deep scratches). The decision to drop back a grit hinges on two constraints: persistence and thickness budget.

Persistence test:

- After two crosshatch cycles at the current grit, if your guide coat still shows concentrated islands or a defect remains visible under raking light, you’re undercutting the problem. Drop back one grit.

- If you’ve already dropped once and the defect still survives two more cycles, drop one more step—but stop there and reassess thickness.

Thickness budget:

- Wood: You generally have more latitude, but watch veneer (typically 0.5–0.7 mm). If a planer track is visible after P120, don’t push P150/180 hoping it disappears; drop to P80 to reset, then climb.

- Automotive clear coat: Typical remaining clear is 30–50 µm on older finishes, 50–60 µm on fresh. A P1500 disc with light pressure may remove ~0.2–0.5 µm per pass dry, less when wet on a foam interface. If you estimate a defect deeper than ~3–5 µm (visible sag edge, etched spot), P1500 will be slow and risky. Drop to P1000–P1200, then refine.

- Polyurethane and alkyd: Flatten nibs at P320–P400, then refine to P600–P800 before recoating. If brush marks telegraph after P600, dropping back to P320 with a hard block is safer than pushing P800 endlessly.

According to a article, aggressive sanding to remove oxidation on automotive finishes can do more harm than chemical decontamination and polishing; reserve coarse grades for structural defects, not cosmetic haze. That aligns with our budget-first rule: if the defect isn’t “geometric,” don’t pay the thickness tax.

Actionable tips:

- Mark and sample: Circle three representative defects, test a 10 cm square on each. If two out of three fail the two-cycle test, drop back a grit globally.

- Use witness lines: For sags/runs, nib the high spot with a razor or hard block first. If the “witness ridge” remains after P1000 in two cycles, drop to P800 for a controlled flatten.

- Count passes: On clear coat, limit yourself to 6–8 medium-pressure passes per cycle. If you exceed 16 total passes at a fine grade without resolution, you’re wasting film—drop back.

- Isolate edges: Edges cut faster. Tape them off while you reset with a coarser grit to avoid breakthrough, then feather with the finer grade at the end.

- Reset pattern: If you suspect random swirls from a soft interface pad, do one corrective cycle on a hard block or direct-to-backing plate to re-straighten scratch geometry before stepping up.

Material-specific playbooks

Wood (hardwoods and softwoods)

Wood defects are often topographical—mill marks, tear-out, glue lines. Don’t try to “polish away” geometry. If you still see planer tracks at P150, drop to P80 or P100 with a firm pad, then re-sequence. For figured woods, silicon carbide wet at P320 can reduce heat and burnishing before dye or sealer. Open-coat aluminum oxide resists loading on resinous softwoods. End grain demands a one-step-lower finishing grade (e.g., side grain P220, end grain P180) to equalize absorption.

Drop-back triggers:

- Persistent torn grain after P120 → drop to P80 with a fresh, sharp sheet.

- Glue bleed lines visible at P180 under alcohol wipe → drop to P120 and local re-flatten.

- Burnished sheen at P220 with low scratch visibility → reset with fresh P180 to cut, then finish at P220.

Film finishes (polyurethane, lacquer, varnish)

Nibs and dust are shallow; brush marks and orange peel are geometric. Start nib removal at P320–P400 on a hard block; if texture remains after P600 in two cycles, drop back to P320. Avoid going below P320 unless you’ve confirmed adequate film thickness for a reflow or recoat. Wet silicon carbide keeps the scratch consistent and reduces loading.

Drop-back triggers:

- Uniform nibs clear at P400, but ridges remain after P600 → drop to P320 on a hard block.

- Dull islands persist after P800 wet sanding → you’re skipping too far; step back to P600.

Automotive clear coat

Work from least to most invasive. Decontaminate, clay, and test polish before sanding. For dust nibs and small inclusions, local P1500–P2000 is appropriate, then compound. For sags/runs, level the crest with a blade or P1000 on a hard interface; if the ridge is still proud after two cycles, drop to P800 briefly, then refine.

Drop-back triggers:

- After compounding, pigtails reveal at certain angles → your P3000 didn’t fully erase P1500 scratches; re-cut at P2000, then P3000 with cleaner technique.

- Acid etch or bird drop crater remains after P2000 → local P1200 with tight control, then refine.

Epoxy and resin

Resin is brittle-glassy; silicon carbide wet is king. Start at P400–P600 for general flattening. If you see ripples after P800, you’re likely sanding atop highs. Use a hard, flat block to re-flatten at P400/600. Avoid overheating; fresh water keeps debris from gouging.

Drop-back triggers:

- Matted low spots holding water after squeegee → drop to P400 to re-level.

- Micro-chips at edges after P800 → reduce pressure, switch to fresh P600 to regain control.

Metals (aluminum, stainless, carbon steel)

Metals demand uniform scratch direction. Ceramic or zirconia alumina cuts aggressively; film-backed aluminum oxide refines predictably. If a weld line won’t disappear after P120 on stainless, drop to P80 with a hard platen, then ladder up carefully: P120 → P180 → P240 → Scotch-Brite or P320 depending on finish spec.

Drop-back triggers:

- Shadow lines after P240 → revisit P180 with a firmer backup and aligned scratch.

Testing, logging, and process control

You’ll make better drop-back calls with small, repeatable tests. Build a simple protocol:

- Track passes: Write the current grit and pass-count on blue tape at the edge of the work. Stick to 6–8 medium passes per cycle before checking.

- Keep a loupe: A 20–40x pocket loupe or USB microscope makes scratch geometry obvious. If the fine grit scratch pattern sits “between” deeper lines, you’ve skipped too far.

- Use solvents for preview: A fast-evap wipe (naphtha on wood, water/alcohol on cured film) reveals whether you’ve truly leveled or just abraded. If a defect darkens under solvent, it’s still geometric.

- Gloss meter and thickness gauges: On finishes, a 60° gloss meter shows whether random haze remains after your final grit. For automotive clear, a paint thickness gauge helps enforce the budget; log readings at multiple spots before sanding.

- Control variables: Pressure, pad hardness, and lubricant change cut rate. Soft interfaces round over peaks and reduce cut—great for final refining, poor for leveling. Water with a drop of surfactant improves debris evacuation during wet sanding and narrows scratch variability.

Trigger thresholds to codify:

- Two failed cycles at current grit → drop one step coarser.

- One failed cycle after a previous drop-back → drop one more step coarser, then reassess thickness before proceeding.

- Exceeded pass budget (e.g., >16 passes total at a fine grade) without progress → you’re polishing the peaks; reset the plane with a harder pad or coarser grit.

Turn these into a checklist you follow every time. Consistency is what lets you diagnose quickly. When your scratch fields are predictable, the decision to drop back is rarely a guess—it’s the next logical step.

How to Sand — Video Guide

There’s a concise walkthrough I like that demonstrates leveling and refining a polyurethane topcoat. It opens with common errors—brush marks, dust nibs, slight valleys—and shows how to start at a mid-grade, around P320, to flatten the high points before climbing to P600 and beyond. The sequence is short but highlights two key principles: control pad hardness for leveling, and don’t jump grits too fast.

Video source: How to Sand Topcoat of Polyurethane

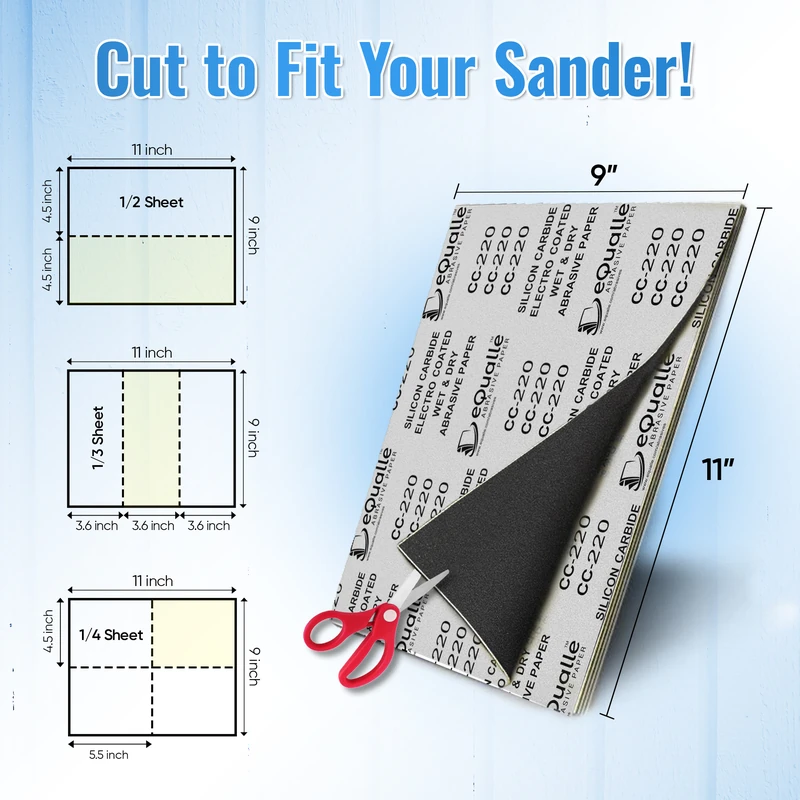

320 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (100-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Precision finishing grit that enhances clarity between paint or lacquer coats, ensuring a flawless final layer. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: How many passes should I try before dropping back a grit?

A: Use two disciplined crosshatch cycles (typically 6–8 passes each) at the current grit. If the defect survives both, drop back one grit and reassess.

Q: Can I skip grits if my surface looks good under light?

A: Yes, but only if your scratch field is uniform and fully erased by the next step. As a rule, avoid jumps larger than one standard step (e.g., P800 to P1500) on hard films.

Q: What’s the safest starting grit for polyurethane nibs?

A: Start at P320–P400 on a hard block to knock down nibs, then refine to P600–P800 before recoating. Drop back only if texture persists after two cycles.

Q: For auto clear coat, how coarse is too coarse?

A: Avoid going below P1000 for most spot defects. Reserve P800 for pronounced runs or dust inclusions after careful thickness checks and tight local control.

Q: Why do scratches reappear after polishing?

A: Often, a fine grit didn’t fully remove deeper scratches or you used a soft interface that rounded peaks without leveling. Drop back one grit, reset with firmer backing, and re-sequence.