Avoid Edge Burn-Through with Wet Dry Sandpaper

Saturday light pools across the driveway. Your project—clear coat mottled with orange peel and a few dust nibs—waits patiently. You’ve gathered your bucket, a soft block, and a stack of wet dry sandpaper sheets, promising yourself you’ll go slow and do it right this time. The first passes are almost meditative: water beads, slurry darkens, and the surface gradually evens out. Then, edging along a fender crease, your heart stutters—you feel it grab. One careless swipe, one ounce too much pressure, and suddenly the gloss gives way to dull haze. You squeegee and look closer. A whisper of primer peeks through at the ridge.

Anyone who’s wet sanded knows the knot in your stomach when an edge burns through. It’s the moment craftsmanship feels fragile. But it’s also the moment skills sharpen. Understanding why burn-through happens—and how to prevent it—turns dread into control. With the right grit, backing pads, and gentle technique, you’ll sand confidently, preserve film build where it’s thinnest, and leave yourself room to polish back a mirror finish. Whether you’re refining a respray or reviving tired clear, wet dry sandpaper is a powerful tool, but it demands respect near edges and body lines. This guide focuses on the subtle adjustments—pressure, angle, lubrication, and grit choice—that keep your correction steady and safe, especially in those high-risk zones.

If you’ve hesitated to sand close to trim, door edges, or character lines, you’re not alone. The good news: small habits have a big payoff. A strip of tape, a softer interface, a better rinse rhythm—all help protect thin coatings without sacrificing results. You’ll finish more evenly, spend less time chasing haze, and avoid those panic moments that can derail a day’s work.

Quick Summary: Prevent edge burn-through by minimizing pressure and heat at high spots, using the right wet dry sandpaper and backing, sanding parallel to edges, and keeping the surface flooded and clean.

Why edges burn through—and how it happens

Edges and body lines are high points: the coating is physically thinner there due to spraying dynamics and gravity. When you sand, pressure and friction concentrate on these ridges, which accelerates removal. Two common accelerants make it worse: dry patches that spike heat and grit, and rigid backing that refuses to flex around contours. The result is rapid material loss where you can least afford it.

Another contributor is grit choice. Coarse abrasives remove peaks fast, but they also cut through film build quickly on the high spots. Even a “safe” grit like 1500 can be unsafe on a ridge if you bear down or stall in one spot. The longer you linger, the more heat you generate—and heat softens the coating, letting abrasive slice more aggressively. It’s why a few light strokes parallel to an edge are safer than cross-grain scrubbing.

Contamination matters, too. A tiny hard particle trapped under the paper can act like a rogue pebble, carving a trough. If you feel a scratchy skip or hear a squeak, stop, rinse, wipe, and reset. Your squeegee is your truth-teller: after a few passes, pull water off the surface. If low spots remain dull while highs brighten quickly, you’re cutting faster at the edges and should adjust immediately.

Finally, consider tool choice. Random-orbit machines are efficient on flats but risky near edges without an interface pad and strict technique. Hand sanding improves feedback and control in tight zones. When in doubt, hand sand edges lightly and machine-sand the broader flats to minimize the chance of burn-through.

Choosing the right wet dry sandpaper grits

Selecting the correct grit sequence is like setting your margin of safety. The more aggressive the starting grit, the less room for error around edges. For most refinement work—knocking down dust nibs or mild orange peel—start finer than you think and let time, not pressure, do the work.

- Fresh clear coat leveling: 1500–2000 grit for initial flattening, followed by 2500–3000 to refine for a clean polish.

- Dust nib removal only: Spot-level with 1500 on a small block (or nib file with extreme caution), then feather the area with 2000–3000.

- Blending old and new paint: Begin at 2000 around edges, reserve 1500 for flatter, safer panels, and finish with 3000 for minimal compound time.

Look for high-quality silicon carbide sheets labeled for wet use—these maintain a consistent cut when flooded and resist loading. Foam-backed abrasives or discs can be even safer on contours, distributing pressure more evenly. When using a machine, pair discs with a 3–5 mm interface pad to keep backing soft at body lines.

Keep your grit steps tight. Jumping from 1500 straight to compound is tempting, but refining to 2500–3000 reduces the time you spend with aggressive compounds (which are themselves a form of abrasion). Every “refine” step adds safety, especially near edges, because you rely less on hard buffing later.

Plan your path: Use 2000 along edges first, with the lightest touch. Then level the flats at 1500–2000 if needed, blending back into the edges with your finer grit. This edge-first approach helps you bank safety where you need it most before addressing broader removal.

Safe techniques for edges and body lines

Edges reward technique more than toughness. Think finesse: float over the ridge, don’t push through it. Eight habits make the difference.

- Tape the edge: Lay 1–2 layers of automotive masking tape directly on the sharp line or exposed edge. This creates a sacrificial barrier that alerts your fingers before the coating disappears.

- Sand parallel to the edge: Align strokes along the edge, not across it. Parallel motion reduces the time abrasive spends perched on the high spot.

- Float the overhang: If you wrap paper around a soft block, let 3–5 mm of abrasive overhang the edge—but keep pressure on the block, not the overhang. This feathers without sawing into the ridge.

- Lift on and off: Start pressure a few centimeters before the edge, lighten as you cross the ridge, and reapply pressure after. No hard stops on the line.

- Use your fingers wisely: If you must hand-sand without a block, back the paper with your fingertips through a thin foam interface. Keep your joints off the edge to avoid point pressure.

Refresh the surface frequently. Rinse the panel and paper, squeegee, and inspect after every few passes. A visual cycle—three strokes, rinse, inspect—lets you catch risk early. Maintain a wet slurry at all times; if the paper grips, it’s too dry or loaded.

A few passes near an edge go a long way. If you’re chasing the last low spot next to a ridge, ask if it’s worth the risk. Often, a later compounding step will remove that faint haze without more sanding. Use your discretion: the finish should be even, not perfect at the expense of film build.

According to a article

Tools, lube, and guides that prevent burn-through

Good tools make safe technique easier. Start with a soft sanding block for flats and a thin foam interface for edges and curves. An interface pad cushions contact, spreading pressure so the abrasive glides rather than digs. If using a DA sander, always add an interface pad when working near body lines, and reduce speed.

Lubrication matters. Mix clean water with a drop of pH-balanced car shampoo or a dedicated sanding lubricant in a spray bottle. The surfactant helps the paper float, reduces heat, and clears slurry. Some prefer a bucket with a grit guard to rinse the sheet; either way, keep the surface flooded. Squeegee between sets so you can see progress instead of guessing.

Use a guide coat if you are leveling texture. A very light dusting of guide coat or dry marker shows highs and lows clearly. On flats, sand until the guide coat just evens out, but ease up near edges—once the ridge is clear of guide coat, transition to a finer grit or stop.

A paint thickness gauge is invaluable if you do this often. While not everyone has one, even an inexpensive gauge can warn you when a panel is thin, or a repainted section varies from adjacent panels. Treat any readings that are lower than surrounding areas with extra caution, especially at cut-through-prone spots like door edges or trunk lips.

Keep consumables fresh. Worn paper can skate and generate heat; loaded paper cuts unevenly and scratches. Replace sheets more frequently near edges than you would on flats. That slightly wasteful habit is cheap insurance against a respray.

Fixing mistakes and blending invisibly

If you do burn through, stop immediately and dry the area. Determine what failed: clear only, or clear plus base. A faint base color showing through clear can sometimes be spot-cleared; exposed primer or metal requires basecoat correction before clear.

Feather the perimeter gently with 2000–3000 grit to soften the transition, keeping pressure off the deepest point. Clean thoroughly with panel prep. For small clear-only breakthroughs, some technicians isolate with a localized clear application, then nib-sand and polish. For base exposure, apply a light, blended basecoat to the region, fade it out beyond the repair, and follow with a blended clear over a wider zone to hide the edge.

When blending, give yourself space. Mask “soft edges” using back-masked tape so you don’t create a hard line. After the clear cures, start with 2000–3000 grit to level the blend zone, working outward. Finish with a measured polish cycle: a medium-cut compound on a foam pad to remove sanding marks, then a fine polish to restore clarity. Keep pads clean and speeds moderate to avoid reintroducing heat.

If a full panel respray is in order, take it as part of the craft. Each mistake teaches touch, timing, and tolerance. Document your process: what grit, how many passes, where it failed. Next time, you’ll spot the warning signs sooner and make adjustments before the edge gives up.

Practical rescue tips:

- If you suspect thin clear at a panel edge, switch to 3000 grit and plan to polish more—it’s slower, but safer.

- When polishing a freshly blended area, tape the very edge again during initial compounding to protect it, then remove for final refinement.

- Don’t chase perfection on the ridge; aim for uniformity that disappears at an arm’s length, then refine gloss with polish rather than more sanding.

HOW TO SAND — Video Guide

A helpful drywaller’s guide titled HOW TO SAND DRYWALL!!! covers sanding poles, sponges, and paper selection from rough shaping to final finish. While focused on walls, the principles translate: choose the right abrasive for the job, step your grits cleanly, and control dust and friction with deliberate movement.

Video source: HOW TO SAND DRYWALL!!!

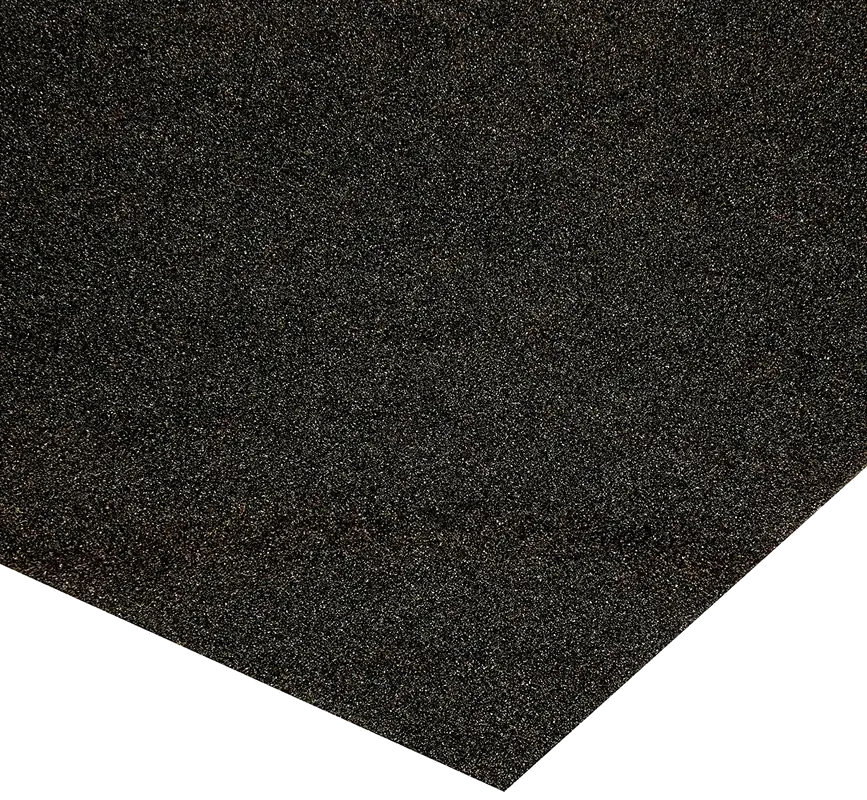

120 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (25-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — High-cut abrasive for refining rough wood grain, removing scratches, and preparing bare surfaces for priming or staining. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: How do I know when to stop sanding near an edge?

A: Squeegee frequently. When the edge clears faster than surrounding areas or begins to brighten uniformly while nearby lows remain dull, switch to a finer grit or stop and plan to polish the rest.

Q: Is machine sanding safe on edges with an interface pad?

A: It can be, but hand sanding gives better feedback. If you use a DA, add a soft interface pad, reduce speed, sand parallel to the edge, and keep passes brief with light pressure.

Q: What should I put in my water for wet sanding?

A: Clean water plus a drop of pH-balanced car shampoo or a dedicated sanding lubricant reduces friction and loading. Avoid harsh soaps that leave film or soften paint excessively.

Q: How can I prevent contaminants from causing scratches during wet sanding?

A: Rinse the panel and the paper frequently, use a spray bottle to flush debris, wipe with a clean microfiber between sets, and replace any sheet that feels scratchy or starts to grab.

Q: I burned through clear on a sharp body line—can polishing fix it?

A: No. Polishing removes more material and will worsen a breakthrough. Stop, dry, assess the layer breached, and plan a localized refinish or blend before returning to polish.