Even Pressure Mastery in Hand Sanding

A fresh sheet of paper crackles between your fingers as you kneel beside a project you’ve put your evenings into—a walnut coffee table top you milled by hand, or maybe a maple guitar body you’ve been carving between jobs. You tell yourself it’s “just sanding,” but you know better. One wrong move and a finger groove shows up under the finish. One heavy corner and the veneer starts to whisper thin. The difference between amateur and pro often shows up right here, during hand sanding, in the quiet, repetitive passes that bring wood to life.

I’ve stood in that same shop feeling impatient, thinking the last 10% couldn’t possibly matter. It does. Even pressure isn’t about pressing harder; it’s about consistency—across the pad, across the board, across every stroke. When your hand sanding pressure is controlled, the surface reads as a single plane, not a map of your movements. Colors pop uniformly, join lines disappear, and edges stay crisp. You finish faster because you’re not fixing mistakes you created a minute ago.

Even pressure is a craft you can learn. It starts in your stance, travels through your grip, and ends at the abrasive. It’s the difference between sanding on your fingertips versus letting a block carry the load. In the next sections, I’ll show you exactly how to set up your body, choose the right tools, and verify your results with quick checks. I’ll also give you a few tricks—like training with a bathroom or luggage scale—to calibrate your touch. This isn’t theory. It’s the everyday system I use in the shop, from flattening panels to dialing in knife bevels and finishing curved chair rails.

Quick Summary: Even pressure in hand sanding comes from body alignment, two-hand support, rigid or semi-flexible backers, grit planning, and constant visual and tactile checks—plus a few simple training drills.

Why Even Pressure Changes Everything

Uneven pressure shows up immediately in wood—and worse, it telegraphs through stain and finish. If you’ve ever seen dark blotches or shiny tracks after a first coat of oil, that’s likely pressure or grit inconsistency, not just “difficult wood.” Your goal is to distribute force evenly across the abrasive so every grain on the sheet does equal work.

Imagine your sandpaper as a plane iron with thousands of tiny cutters. If your fingertips push harder in one spot, those cutters dig deeper and create a trough. If the heel of your hand is light, the surface stays untouched there and you chase that low spot for the next 20 minutes. On flat work, this creates shallow dishes. On edges, you’ll roll them. On curves, you’ll flatten high points and lose the intended profile.

Core principles:

- Keep the abrasive supported. Unsupported paper follows the softness of your flesh and carves dips. A block or backer spreads pressure.

- Move the work uniformly. Same speed, same stroke length, same overlap. Your motion should be as consistent as your grip.

- Respect grit progression. If you jump grits or stay too long at one, you’ll overload the paper, push harder, and introduce pressure errors.

What uneven pressure sounds like:

- Paper squeals or chirps on the high spots.

- The stroke feels grabby on one edge and floaty on the other.

- You see “shiny stripes” under raking light—the hallmark of local pressure.

Three quick fixes you can apply today:

- Use two hands: one to guide, one to load. Your shoulders do the pushing, not your fingers.

- Draw pencil guide lines. Sand until the pencil disappears uniformly.

- Sand with the grain on final grits, but cross-grain or diagonally at lower grits to level efficiently, then remove those scratches methodically.

Grip, Posture, and Rhythm for Hand Sanding

Even pressure starts with how you stand. You want your body to deliver force in a straight line through the backer and into the work—not through bent wrists or flexed fingertips.

Posture and alignment:

- Plant your feet shoulder-width apart. Square your shoulders to the workpiece.

- Bend slightly at the hips, not the waist, and keep your spine neutral. This lets you shift body weight forward and back without wobble.

- Keep wrists straight. A bent wrist loads one edge of the block more than the other.

The two-hand technique:

- Dominant hand holds the front of the block (or sheet) as a guide.

- Support hand rests on the back, applying gentle, even load. Think “cover the block,” not “press on a point.”

- Distribute fingers so they mirror the block’s footprint. If you’re using a 3x5 block, spread your fingers across that area, not bunched in the middle.

Rhythm and stroke:

- Aim for consistent, overlapping passes—about 50% overlap per stroke.

- Keep speed steady. If you sand fast over open areas and slow at edges, you’ll dig the edges.

- Count strokes on repeated parts: for example, 10 strokes per quadrant, rotate, then repeat. This is crucial when matching legs, rails, or knife sides.

Pressure calibration drill:

- Place a bathroom or luggage scale on the bench. Put your sanding block on the scale and press as you would while sanding. Note the readout—most hand sanding should be around 1–3 pounds of force for leveling grits, and lighter for finishing grits. Practice until you can hit the same number repeatedly without looking.

- Practice the “flat palm” test: lay your palm fully over the block and sand a minute with feather-light pressure. Feel the paper cutting without forcing it. That’s your baseline.

Tips you’ll use every day:

- Keep elbows slightly tucked—flared elbows twist the block.

- Stop, dust off, and look every 30–60 seconds. Monitoring is part of maintaining even pressure.

- When switching hands or sides of a piece, mirror your posture so your pressure pattern stays consistent.

Blocks, Backers, and Abrasives That Help

Your backer is your pressure manager. The more uniform the backer, the more uniform your results. For truly flat surfaces, you need a block stiffer than your flesh. For gentle curves, you need controlled flexibility.

Smart backer choices:

- Rigid blocks (MDF, hardwood, aluminum): Ideal for flattening panels, jointed edges, and knife bevels. A 3/4-inch MDF offcut with cork or thin rubber glued on makes a great flat backer with a hint of give.

- Semi-flex blocks (dense rubber, 3D-printed blocks, EVA foam): Perfect for subtle curves and profiles where you still want distributed pressure. A tough rubber sanding block holds the paper firmly and evens out your hand pressure across the whole face.

- Custom contour sticks: Wrap paper around dowels, radiused blocks, or even socket extensions to match inside curves, so you’re not overloading a single point.

Abrasive and paper handling:

- Use high-quality paper that cuts cleanly. Dull paper makes you press harder, which ruins pressure control.

- Change paper early, not late. If it stops cutting, swap it. Fresh paper lets you stay light and even.

- Tear consistent sheets and fold them with cut edges aligned. Unruly corners snag and force you to lift an edge.

Paper attachment matters:

- For blocks with clips, tension the paper equally on both sides.

- For PSA (sticky-back) rolls on a flat block, burnish across the whole face to avoid bubbles that create high spots.

- For hand-only work, fold a third over so your fingers push through two layers—this stiffens the pad slightly and spreads force.

Reference check tools:

- Use a pencil grid to reveal low/high zones.

- Use raking light from a clamp light or phone flashlight set low to the surface to identify pressure streaks.

- Keep a small straightedge or known-flat ruler at hand; a quick pass across the surface tells you if you’re dishing.

According to a article, keeping the pad flat and avoiding excessive force are key—good reminders that your backer selection and a gentle touch often matter more than muscle.

Step-by-Step: Flat Panels and Edges

If you’re flattening a tabletop or door panel, your workflow must remove material evenly and then refine without introducing new lows. Here’s a clean, repeatable process.

Step 1: Map the surface

- Draw a light pencil grid across the panel.

- Identify known trouble spots: around knots, glue lines, and edges.

Step 2: Choose your backer and grit

- Start with a rigid block and an appropriate leveling grit—usually 120 or 150 for planed surfaces, 80–100 if you’re dealing with mill marks or slight cup.

- For edges, use a block as long as the edge, or work in overlapping sections with a shorter block to avoid rocking.

Step 3: First passes—diagonal leveling

- Sand diagonally at about 30–45 degrees to the grain. Use long, even strokes with two hands on the block.

- Apply about 1–2 pounds of pressure—steady, not stabbing. Keep your wrist straight to avoid loading one corner.

- Work the whole surface in a consistent pattern: upper-left to lower-right, overlapping, then switch diagonals.

Step 4: Verify and adjust

- Wipe dust, check the pencil. If some marks remain, you’ve got low spots. Stay with the same grit and keep working diagonally until the marks fade uniformly.

- Check flat with a straightedge or by placing the block across the area and rocking; no rock means you’re staying flat.

Step 5: With-the-grain refinement

- Move to the next grit (120 to 150, 150 to 180, etc.). Sand with the grain using light, consistent passes. This removes diagonal scratches and evens any micro-variations in pressure.

- For edges, keep the block fully supported on the edge—no rolling over. Stop your stroke before the far corner, lift, and reset to avoid rounding.

Step 6: Final checks

- Use raking light to scan for shiny streaks (high-pressure tracks) or dull patches (low-pressure zones).

- Feel with your whole palm, not fingertips. Your palm senses planes; fingertips hunt texture and can mislead you into overworking small spots.

Edge-specific tips:

- Clamp a sacrificial board flush to the edge to support the exit and prevent roll-off.

- Treat edges like a miniature panel: consistent strokes, centered pressure, and frequent checks.

- If you must break an edge, do it intentionally with a few light strokes at 45 degrees, not by accident from uneven pressure.

Hand Sanding Curves, Profiles, and End Grain

Curves require even pressure that follows the form without flattening it. Your tools and touch must match the geometry.

Backers for curves:

- For outside curves, use a semi-flex block or wrap paper around a firm foam to spread load yet conform.

- For inside curves, match the radius with dowels, pipes, or custom-cut radiused blocks. Don’t rely on finger pads alone—they’ll dish the curve.

- For complex profiles (moldings), use profile sanding pads or make quick custom forms with casting rubber or shaped cork.

Technique on curves:

- Shorter strokes maintain shape better than long sweeps that average over highs and lows.

- Rotate the work or your stance so your pressure stays perpendicular to the tangent of the curve—this prevents bias to one side.

- Keep your support hand centered over the contact area; do not “pinch” the paper at the edges.

End grain tactics:

- Start one grit lower than side grain because end grain is tougher and drinks finish.

- Use a firm backer even on small end grain areas; circular fingertip motions will leave divots that show under finish.

- Finish by burnishing lightly with higher grit to close the pores uniformly.

Micro-control drills:

- Draw contour lines across a curved rail and sand just until they fade evenly. This trains your eye for pressure uniformity along a curve.

- Use a metronome app or count a steady cadence while sanding complex shapes—rhythm helps keep your force and stroke length even.

- For knife blades or tool bevels, use a hard sanding bar and pull strokes spine-to-edge or heel-to-tip, alternating sides with the same stroke count to avoid asymmetry.

Actionable tips you’ll use on curves and end grain:

- Keep paper fresh; dull paper on end grain forces excess pressure.

- Don’t chase a single scratch with fingertip pressure—work the entire zone with your backer.

- Stop and re-chalk with pencil when you lose track of shape; guide marks are cheap insurance.

Troubleshooting and Pro-Level Checks

Even when you do most things right, small pressure errors sneak in. The fix is to diagnose quickly and correct without removing unnecessary material.

Common symptoms and fixes:

- Shiny streaks after a pass: You’re loading one edge. Re-center your hand and verify your block is flat. Reduce pressure and let fresh paper cut.

- “Cathedral” dips on panels: Fingertip sanding without a block. Switch to a rigid backer, redraw the grid, and level diagonally until flat.

- Rounded edges: You’re rolling off. Stop strokes just short of the far edge, and consider a fence or sacrificial partner board.

Verification methods:

- Raking light: Move a light low across the surface; streaks run parallel to your pressure bias.

- Pencil and erase pattern: Lightly mark, sand a uniform number of strokes, inspect what’s left. Remaining pencil = low spots.

- Feel tests: Lay a fresh, flat razor blade on the surface and try to rock it. Any rock indicates a crown; any gap shows a dish.

Pro checks and habits:

- Caliper consistency: On repeated parts (edges, rails), use calipers to confirm thickness before and after a sanding sequence. Uneven numbers mean uneven pressure somewhere.

- Time symmetry: If you sand one side for 2 minutes, sand the mirrored piece for 2 minutes with the same strokes and pressure.

- Paper rotation: Rotate your paper or block 180 degrees halfway through a sequence to average out any natural bias in your hands.

When to start over:

- If you’ve chased a low spot at 220 grit for more than a couple of minutes, step back a grit or two and re-level with a rigid backer. Higher grits aren’t for shaping; they’re for refining.

Three final pressure-discipline tips:

- Lighten up as you go up in grit. By 220–320, your pressure should be barely more than the weight of your hands and block.

- Clean as you go. Dust under the paper creates micro-highs that mimic pressure errors.

- Keep your blocks honest. If a block gets dinged or crowned, true it or replace it—your surface can’t be flatter than your backer.

Beginner Sanding Mistakes — Video Guide

If you’re more of a visual learner, there’s a helpful video on common beginner mistakes in sanding that demystifies what “not hard, but skillful” really means. The presenter walks through pressure control, keeping the pad flat, and why rushing or pushing down only creates more work later.

Video source: Beginner Sanding Mistakes | How to Sand

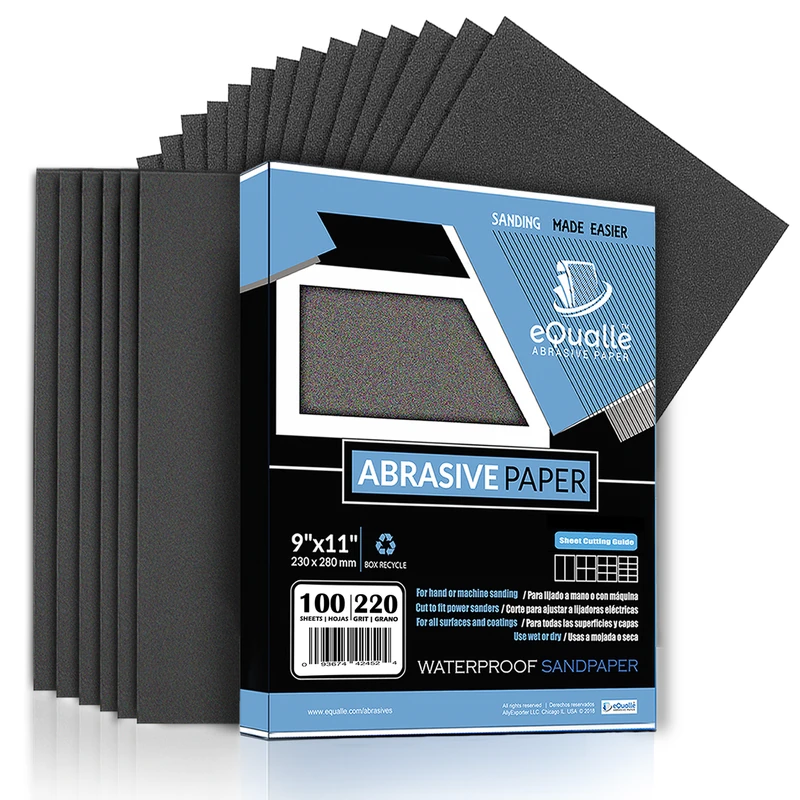

80 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (50-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Durable coarse abrasive that evens out irregular surfaces and clears old coatings. Ideal for early sanding stages in woodworking, fiberglass, or metal preparation. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: How much pressure should I use when hand sanding?

A: For leveling grits (80–150), aim for roughly 1–3 pounds of force with a rigid backer; for finishing grits (180–320+), lighten to just the weight of your hands and block. Use a bathroom or luggage scale to practice hitting the same pressure consistently.

Q: Do I really need a sanding block for flat surfaces?

A: Yes. A rigid or semi-flex block spreads force across the sheet, preventing fingertip grooves and dishes. Your surface can’t be flatter than your backer, so choose a block that matches the goal—rigid for flats, slightly flexible for gentle curves.

Q: Why do shiny streaks appear after sanding?

A: Shiny streaks are often pressure tracks—one edge of the paper is doing more work. Re-center your hand, verify the block is flat, and use light, even passes with fresh paper. Raking light helps you spot and correct them early.

Q: How often should I change sandpaper?

A: As soon as cutting slows or dust smears instead of powders. Dull paper makes you press harder, which ruins even pressure. On resinous woods or end grain, expect to change more frequently.

Q: Is sanding diagonally bad for the grain?

A: Not at leveling grits. Diagonal passes help flatten efficiently. Follow with with-the-grain passes at the next grit to remove diagonal scratches and lock in a uniform surface without pressure artifacts.