Best Sandpaper Grits for Precise Wood Sanding

A Saturday morning sunbeam revealed everything—the faint planer tracks on a maple tabletop, a small divot near an edge, and those whisper-thin swirls you only notice after the first coat of finish. A project that looked “almost ready” under overhead light suddenly felt two steps backward under raking light. That moment is where quality begins: in choosing the right starting grit and a disciplined progression that erases, rather than buries, defects. This is the decisive difference between passable and professional surface prep.

For many, wood sanding begins with a guess: grab 120 grit because it feels “safe.” But sanding is a controlled process, not a guess. Each abrasive grade leaves a predictable scratch depth, and every step in your sequence must fully delete the previous scratch pattern before you move on. Skip too far and you preserve ghosts; start too fine and you waste time burnishing defects rather than removing them. The consequence shows up later under dye, stain, or a high-gloss film finish, where optical clarity is merciless.

When you understand your material, your defects, and your abrasive system, sanding becomes as measurable as planing thickness or setting a jointer fence. Pencil-guided passes under raking light, vacuum-assisted dust collection, and a stepwise grit sequence will get you there. Whether you are prepping a presurfaced board for an oil finish or rescuing a resin-heavy softwood shelf loaded with swirl marks, the right grit choices—and the discipline to verify each step—turn wood sanding into a repeatable, high-yield workflow.

Quick Summary: Select your starting grit based on the worst defect, then progress in controlled steps that fully remove prior scratches, validated by raking light and clean dust extraction.

Start where the wood is

Sanding does not begin at a favorite grit; it begins at the worst visible defect. Your starting grit must be coarse enough to fully cut below planer knife marks, milling ripple, tear-out, glue squeeze-out, or scratches from previous operations. For heavy stock removal or flattening, 40–60 grit is appropriate. If your surface shows clear planer tracks or moderate mill marks, 80 grit removes them efficiently without digging unnecessary valleys. On a freshly planed board in good condition, 120–150 can be a sensible starting point—especially on diffuse-porous hardwoods that sand uniformly.

Use inspection techniques to guide that choice:

- Raking light at 15–30 degrees reveals scratch orientation, chatter, and low-frequency undulations that overhead light hides.

- Pencil crosshatch the surface. Sand until all lines disappear evenly; any lingering marks signal low spots or inadequate cutting.

- Feel for heat. Excess heat indicates dull abrasives, clogged paper, or too much pressure—conditions that polish defects rather than cutting them.

Remember that scratch depth scales with abrasive particle size: typical FEPA grits leave approximate scratches of P80 ≈ 200 µm, P120 ≈ 125 µm, P180 ≈ 80 µm, and P220 ≈ 65–70 µm. If you begin too fine on a surface that needs heavy correction, you will spend far longer than starting with 80 and stepping through logical increments. Conversely, don’t start at 60 on a cabinet door that only needs nib removal—overly coarse paper lengthens your workflow and risks telegraphing deep scratches into edges and profiles that are hard to clean up.

Routinely re-evaluate after the first pass. If 120 isn’t erasing planer lines in two to three minutes on a 2×4 ft panel with a random orbital sander, drop to 80. It’s faster to step back once than to grind at an undersized grit while glazing the surface.

Grit logic for wood sanding workflows

Effective grit sequencing is a controlled deletion of scratches. As a benchmark, moving between grits by a factor of about 1.4–1.6 in particle size provides reliable scratch removal without redundant steps. In practical shop terms, that translates to step-ups like 80→120→150→180→220 for clear film finishes, or 80→120→180 for oil/varnish blends where 220 might slightly reduce stain uptake.

Typical sequences by scenario:

- Presurfaced hardwoods: Start 150, then 180, finish 220 when aiming for waterborne or high-gloss finishes. For penetrating oils, stop at 180 to maintain consistent color.

- Planer-milled stock with light knife marks: 80→120→180; add 220 only if your topcoat demands optical gloss.

- Heavy correction/flattening: 60→80→120→150/180. Don’t jump directly from 60 to 150—residual deep scratches often reveal themselves after finishing.

- End grain cutting boards: 80→120→150→180→220 (at minimum). End grain swells and polishes differently; water-raise, dry, and resand at the final two grits for crisp clarity.

Consider species. Resinous softwoods (pine, fir) benefit from open-coat, stearated papers to reduce loading; often stop at 180 before stain. Ring-porous hardwoods (oak, ash) tolerate 180–220; diffuse-porous species (maple, birch) can show burnishing at 220+, so test if you plan to stain. For waterborne finishes, pre-raise the grain after your penultimate grit: wipe with a damp cloth, let dry, then make a light final pass at the same grit. This prevents micro-roughness after the first coat.

For edges and profiles, reduce step count but tighten control: hand-sand with flexible foam-backed abrasives or film-backed sheets in 180→220 to avoid flat-spotting. On veneered panels, never begin coarser than 150; veneer thickness leaves no safety margin for deep scratches.

Match abrasives to tools and geometry

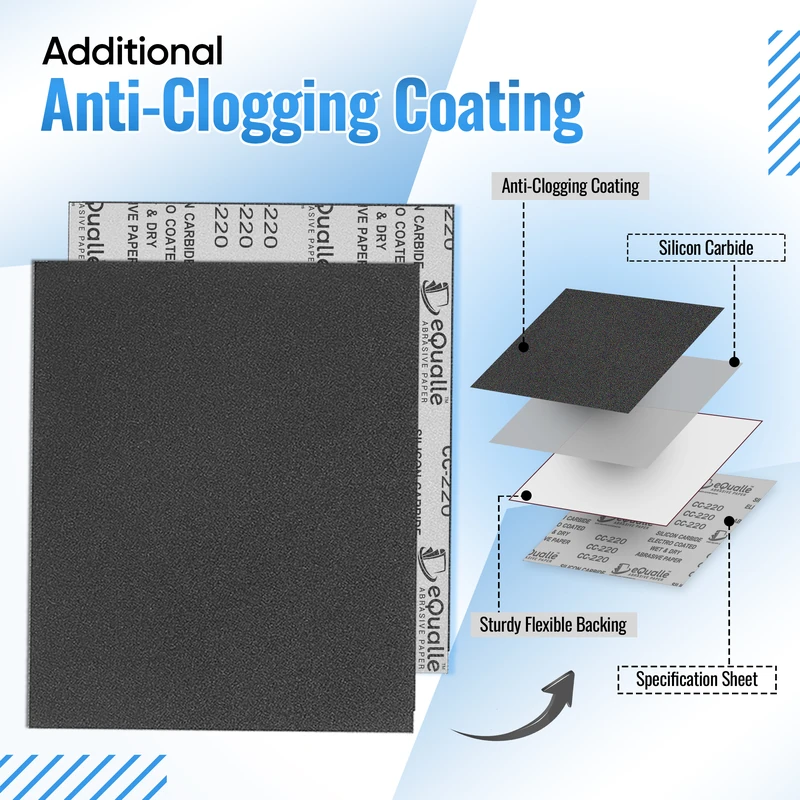

Abrasive performance is a three-part system: mineral, backing, and machine. Aluminum oxide is the all-rounder for wood, providing good cut rate and wear resistance at 80–220. Ceramic alumina excels for high-pressure stock removal (60–80 grit) on belt sanders and drum sanders; it self-sharpens under load. Garnet cuts cleanly on bare wood but dulls quickly; it can be pleasant for hand sanding between coats. Closed-coat sheets cut aggressively on hardwoods; open-coat reduces loading on softwoods and finishes. Stearated coatings further resist clogging when sanding paint or resin-rich timbers.

Backings matter. Paper weights A–F trade flexibility for durability; A/B facilitate conforming to profiles, while C–F suit flat sanding and belt applications. Film-backed discs produce very uniform scratch patterns—excellent for high-visibility surfaces at P180–P320. Cloth backings dominate belts where tensile strength is critical.

Random orbital sanders (ROS) are the primary workhorses for flat panels. Key variables:

- Orbit size: 3/32 in (2.5 mm) for finish control; 3/16 in (5 mm) for faster stock removal.

- Pad hardness: soft for contours, medium for general work, hard for edge crispness and flatness.

- Interface pads: a 1/8–1/4 in foam interface protects hook-and-loop pads and conforms over minor curvature; expect a slightly softer scratch.

Dust extraction is not optional. Clean extraction not only protects lungs but preserves cutting edges and shows defects sooner. Align disc holes precisely to pad holes; a misaligned disc loads fast and creates heat, which rounds abrasive edges and polishes rather than cuts. Vacuum that achieves near-HEPA capture with adjustable suction prevents disc stalling on thin panels.

For tight corners and profiles, detail sanders with triangular pads and thin film abrasives shine. On edge-banding or veneer, hand blocks with cork or rigid foam provide flatness control machines can’t guarantee. Wetting end grain to raise fibers before the final two passes sharpens detail.

According to a article, starting at 150 on well-planed stock is often sufficient—a useful reminder that appropriate starting grit minimizes steps and risk.

Abrasive minerals and backings

- Aluminum oxide: universal, economical, reliable for 80–220.

- Ceramic alumina: high-pressure, coarse grits, belt/drum sanding.

- Silicon carbide: excellent for between-coat flattening and finishes; sharp but brittle.

- Film backing: most uniform scratch, ideal for pre-finish passes.

- Stearate coating: reduces clogging on softwood and finishes; avoid before glue-up.

Surface preparation beyond grit numbers

Sanding success is also about managing wood behavior. Moisture content around 6–9% provides consistent cutting and predictable fiber spring-back. If the workpiece has moved from a humid garage to a heated shop, allow acclimation time; otherwise, fibers reorient after sanding and print through your finish.

Raise the grain deliberately for waterborne systems. After your penultimate grit, wipe the surface with a damp cloth to slightly swell fibers, let dry thoroughly, then repeat the same grit pass to shear off the raised tips. This yields a notably smoother first coat with less post-coat abrasion needed.

Glue management matters. Remove squeeze-out mechanically (scraper) before sanding—a smudged glue film can polish and seal wood, blocking stain. On oily exotics (teak, ipe), wipe with a fast-evaporating solvent before the final pass to minimize loading and burnishing; then sand lightly at the last grit. For blotch-prone species (pine, cherry, maple), consider a pre-stain conditioner after stopping at 180, then finish-sand lightly at 220 if required by the product system.

Dust control is part of the finish. Use a brush nozzle to vacuum the surface after each grit, followed by a microfiber wipe. Compressed air is helpful but can drive fines into pores on open-grain woods; vacuum first, then air if needed. Keep your abrasives fresh: a disc that looks fine but feels slick is dull—replace it. The cost of a new disc is trivial compared to the labor of re-sanding after flaws show under finish.

Consider sequence alignment with finishing goals. If you intend to dye maple, stopping at 150–180 enhances uniform uptake; sanding to 220–320 can reduce color intensity. For catalyzed finishes requiring impeccable optical quality, extend the sequence to 320 with film-backed abrasives and hard pads, then scuff between coats with 320–400 silicon carbide.

Profiles, edges, and veneer

- Edges: Use a hard block at 180–220 to maintain crisp arrises; slightly break edges after final pass to prevent finish chip-out.

- Profiles: Foam-backed abrasives at 180–220 conform without flattening detail; avoid coarse grits that undercut profiles.

- Veneer: Start 150–180, light passes only; monitor heat to avoid glue line creep.

Diagnostics and troubleshooting the finish

Reading the surface is a technical skill. Swirl marks from ROS “pigtails” are tiny comma-shaped scratches caused by embedded debris or a torn abrasive grain; they often appear after finishing. Prevent pigtails by vacuuming between grits, discarding any disc that touched the floor, and avoiding excessive pressure that fractures grains. If pigtails appear at 180, drop one step (to 150), remove them fully, then proceed.

Loading presents as shiny, melty spots on the disc and a squeaky glide—common on resinous softwoods and heat-prone exotics. Solution: switch to open-coat, stearated paper; reduce pressure; increase pad speed while maintaining surface speed; and ensure strong dust extraction. Burnishing (surface polish without cut) occurs when sanding too fine too soon or pressing too hard with a dull disc. The fix is counterintuitive: go coarser, cut properly, then return to your sequence.

Directionality matters. After planing or scraping, start with a grit that can effectively erase tool marks, then allow the ROS to randomize the scratch field. For hand-sanding between grits, follow the grain gently to remove any residual cross-grain marks left by machines, especially on clear-finished pieces.

Five field-proven tips you can apply immediately:

- Map defects before sanding: under raking light, circle chatter, glue, and low spots with a pencil; confirm removal after each grit.

- Use the 90-second rule: if a grit isn’t erasing prior scratches uniformly on a 2×2 ft area in about 90 seconds with a ROS, either your disc is dull or the grit is too fine—adjust.

- Keep discs clean: knock loaded discs against a rubber cleaning stick between passes; retire them at the first sign of glazing.

- Standardize pressure: let the machine’s weight do most of the work; pressing hard increases heat, reduces cut, and creates swirls.

- Validate with alcohol wipe: a quick denatured alcohol wipe flashes off fast and temporarily reveals hidden scratches before finishing.

When you hit your target, the surface under raking light shows a uniform, fine, nondirectional matte with no visible troughs or cross-grain lines. From there, your first coat should lay flat, with minimal grain raise, and only a light scuff required before the next coat.

The Only 3 — Video Guide

A concise, practical video breaks wood sanding down to three core grits, arguing you can cover most work with a lean kit rather than a drawer full of paper. The presenter walks through when to deploy each grit, how to avoid redundant steps, and which affordable abrasive products provide the best value without compromising cut rate or finish quality.

Video source: The Only 3 Sandpapers You Really Need | SANDING BASICS

80 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (10-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Durable coarse abrasive that evens out irregular surfaces and clears old coatings. Ideal for early sanding stages in woodworking, fiberglass, or metal preparation. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What’s the best starting grit for presurfaced hardwood?

A: If the board is truly flat and free of visible planer tracks, start at 150. Confirm with raking light and a pencil map; if mill marks persist after a minute or two with a ROS, drop to 120, clear the defects, and then resume your sequence.

Q: Should I always sand to 220 before finishing?

A: Not always. For oil or oil/varnish blends, 180 often yields better color and mechanical tooth. For waterborne or high-gloss film finishes, 220 is common, sometimes extending to 320 with film-backed abrasives for optical clarity. Match your final grit to the finish system and species.

Q: How do I avoid swirl marks from my random orbital sander?

A: Use quality discs, align dust holes, maintain strong extraction, and avoid heavy pressure. Replace any disc that feels slick or shows tears. Vacuum and wipe between grits, and don’t skip steps; pigtails are frequently the result of fractured abrasive grains or debris under the disc.

Q: Is it worth paying more for ceramic abrasives?

A: For coarse grits (60–80) under high pressure—belt/drum sanding or aggressive ROS passes—ceramic alumina cuts faster and stays sharp longer, often reducing total disc usage. For mid-finish grits (150–220) on a ROS, premium film-backed aluminum oxide typically offers the best balance of cost, uniform scratch, and durability.

Q: How do I sand end grain for a smooth, non-fuzzy surface?

A: Progress more conservatively: 80→120→150→180→220, water-raise before the last pass, and use a hard pad or block to keep fibers sheared rather than pushed over. Avoid overheating; clean discs frequently to prevent burnishing and fuzz.