Wet Sanding Clear Coat: Soak Time That Works

Saturday morning in the shop, coffee steaming on the bench, the hood you painted last weekend stares back with a stubborn peel and a couple of dust nibs. There’s a bucket by your boots and a fistful of dark gray sheets curling at the corners. You know the next hour will make or break the finish—this is the moment where patience and process turn wavy reflections into a razor-straight mirror. When you’re wet sanding clear coat, the way you prepare your abrasives—specifically how long you soak them—can be the difference between an easy, controlled cut and a chewed-up mess that forces a respray. I’ve watched pros ruin perfect paint because they rushed the soak. I’ve also seen hobbyists hit glass-smooth results their first time by dialing in this one simple variable.

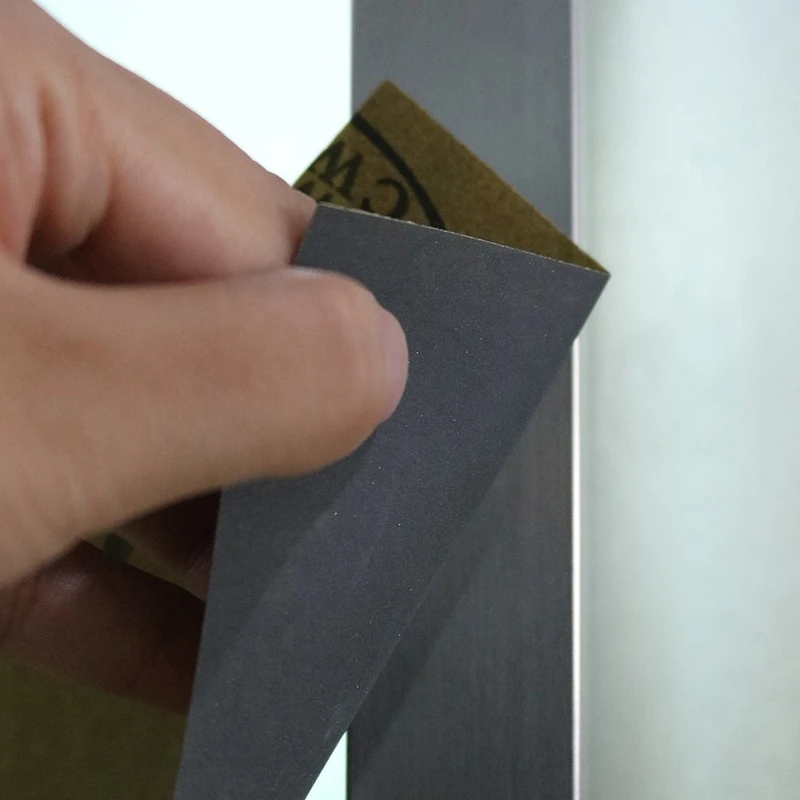

So you dunk a 1500-grit sheet, watch the bubbles bleed away, and feel the backing soften between your fingers. The paper becomes pliable, edges less aggressive, the cut more even. You glance at the clock. Five minutes? Ten? Is more better? Not always. For latex-backed sheets, soaking settles the paper and primes the resin; for film discs, soaking can wreck the adhesive. Two tools that both “sand wet” but ask for opposite prep routines. And that’s where a lot of folks get crossed up—confusing the needs of the abrasive with the needs of the surface.

In my shop, I treat soak time like I treat clamp pressure: just enough, always intentional. Today I’ll show you how to read the paper, match soak time to the grit and backing, and set up a clean, predictable workflow whether you’re cutting orange peel off automotive clear, leveling a lacquered guitar body, or smoothing epoxy on a river table. No mystique—just a process you can repeat, sheet after sheet.

Quick Summary: Pre-soak latex-backed wet/dry sheets 5–15 minutes, don’t soak film or PSA discs, keep the surface flooded, and adjust soak based on backing, grit, and task.

Why Soaking Abrasives Matters

Wet sanding works because water carries away swarf, keeps the abrasive cool, and reduces clogging that leads to random deep scratches. Soaking is about conditioning the backing and adhesive system holding that abrasive. Most wet/dry sheets use a latex-impregnated paper with a resin bond over silicon carbide. A short bath lets the fiber swell and relax, making the sheet flexible enough to wrap blocks and conform to curves without creasing. It also softens the first contact so the sheet doesn’t “grab” at edges or high spots.

If you skip the soak on paper sheets, you’ll notice two things: the sheet tends to skate dry for the first few passes, and the corners are more likely to dig. That’s when you see those crescent scratches that refuse to buff out. On the flip side, over-soaking paper (hours, not minutes) can weaken the bond and shed grit prematurely, especially with budget sheets. With discs, the story changes: film-backed abrasives don’t need—or want—soaking; the plastic doesn’t absorb water, and the hook-and-loop or PSA adhesive can degrade.

Soaking also lets you pre-wet the sheet so it carries water onto the panel with every stroke. That keeps your slurry moving and your cut consistent. If you’ve ever felt a sheet suddenly “stick,” that’s usually the moment lubrication runs thin. Proper pre-soak widens the margin before that happens.

Tips from the bench:

- Use lukewarm water (not hot). Warm water speeds saturation without softening the resin too much.

- Round the sharp corners of a fresh sheet with a single scissor snip to reduce edge scratching.

- Label buckets by grit family (e.g., “1000–2000”) to keep contamination down.

- If you’ll wrap a hard block, pre-soak the paper and lightly dampen the block so the sheet lays flat and stays put.

Soak times when wet sanding clear coat

Clear coat is unforgiving: too dry and you grind in tracks, too aggressive and you break through. When I’m wet sanding clear coat specifically, I treat soak time as part of the grit plan.

Working by hand with latex-backed silicon carbide sheets:

- 800–1000 grit for initial texture leveling: soak 10–15 minutes. You want the sheet pliable enough to knock down orange peel without the corners biting.

- 1200–1500 grit for refining: soak 8–10 minutes. The finer resin systems saturate faster; you don’t gain much by going longer.

- 2000–3000 grit for pre-polish: soak 3–5 minutes. At these grits you’re refining microtexture; long soaks don’t help and can soften the sheet too much.

Film-backed hook-and-loop discs (DA sander):

- Do not pre-soak. Keep a spray bottle or squeeze bottle on the panel and a clean pad; mist frequently, wipe slurry often. Film doesn’t absorb water—soaking only invites adhesive failure at the hook face.

Micro-mesh cloth and cushioned abrasives:

- Pre-wet only. A 1–2 minute dunk or a thorough spray is enough to charge the surface. Long soaks make the cloth floppy and reduce control.

PSA discs:

- Never soak. Water will creep under the adhesive and you’ll sling a loose disc across the shop. Pre-wet the panel instead.

Practical sequence for a typical hood:

- Mark the peel lightly with a grease pencil grid. Soak 1000 grit 10 minutes, wrap a soft interface block, and sand in straight strokes, two passes north–south, two passes east–west. Keep the surface flooded.

- Switch to 1500 grit soaked 8 minutes. Reset the grid and repeat, checking under a strong LED.

- Finish with 2500–3000 grit soaked 3–5 minutes for a uniform haze ready for compound.

If the panel is freshly cured (under 48 hours), err short on soak and light on pressure; newer clears can be a touch softer and load the sheet faster. On aged or hard clears, full recommended soak times give you the control you need without digging.

Paper vs. film vs. foam: soak or not?

You’ve got choices: paper sheets, film discs, foam-backed sanding pads, and micro-mesh. Each behaves differently in water, so treat soak time as a material property, not a superstition.

Latex-backed paper sheets (silicon carbide): These are the classic wet/dry sheets. Short soaks (5–15 minutes) soften the backing and stabilize the cut. They’re ideal for hand sanding with blocks or wrapped around rubber squeegees. If a sheet won’t lay flat after soaking, flip it in the water and massage gently—don’t crease it. Replace when the cut dulls; a lazy sheet makes you press harder, which risks strike-through.

Film-backed discs (hook-and-loop): Film is dimensionally stable and doesn’t absorb water, which is great for an even scratch pattern on a DA. But soaking undermines the hook face and can trap slurry at the interface. Keep them dry; lube the surface. If you need extra cushion, add a foam interface pad—but keep that pad dry. A wet foam pad hydroplanes and rounds edges excessively.

PSA (pressure-sensitive adhesive) discs: The adhesive and paper layers don’t tolerate soaking. Apply them to clean dry backing plates and control lubrication at the panel. If a PSA disc edges up from water creep, peel it off and pitch it. Don’t risk a flying disc.

Micro-mesh and cushioned cloth systems: These want moisture to slide, not a bath to soak. Give them a quick pre-wet with a spray, or dunk for a minute and blot. They shine for polishing curves like guitar bouts or helmet edges.

Foam abrasive pads: Most manufacturers design these for damp sanding, not submerged soaking. Dip and squeeze out; you want damp, not dripping.

According to a article.

The rule of thumb: if it has a paper fiber that swells, a short soak helps. If it’s film or relies on adhesives to stick to a pad, skip the soak and keep the work surface wet instead. Gray areas exist—some premium “no-soak” papers have sealed backs—but even those benefit from a minute under water to kill the initial drag.

Water, additives, and buckets that work

Your soak water is part of the tool. Set it up like you would a glue-up: clean, organized, predictable.

Water choice: Tap water is fine in most shops. If your tap is hard or rusty, use filtered or distilled to avoid mineral tracks. Cold water slows saturation; lukewarm (not hot) speeds it up and keeps your hands happy in winter.

Additives: A couple drops of odorless dish soap per quart breaks surface tension and helps slurry float. Too much soap and you’ll lose feel and build excess foam, which hides defects. For automotive clear, a capful of body-shop safe car wash in a gallon bucket works. Skip oils and silicone—those contaminate paint and will fight your compound later.

Two-bucket method: Treat it like sanding and rinsing. Bucket A is your soak tank with clean water and a few drops of soap. Bucket B is a rinse tank for your sheets and blocks to shed grit. Keep a third squeeze bottle at the panel to flood high spots when needed. Swap water when it goes gray; dirty slurry is a scratch factory.

Grit guards and covers: Drop a grit guard at the bottom of each bucket so shed particles settle below where you’re grabbing sheets. Put a lid on the soak bucket if you’re working all day; keeping dust out is as important as keeping water in.

Storage: You can keep pre-soaked sheets submerged in a sealed container for a day or two. Add a splash of isopropyl (5%) to discourage mold if you’re in a humid shop. Store by grit in separate zip bags submerged within the tub to avoid cross-contamination.

Actionable setup tips:

- Keep a microfiber towel dedicated to blotting between grits; never wipe a 3000-grit haze with the rag you used at 1000.

- Change to a fresh sheet as soon as the slurry darkens fast or the feel goes “skaty”—that’s loading.

- For edges and body lines, switch from a hard block to a soft foam wrap and count strokes; edges vanish faster than flats.

From soak to stroke: technique that saves finishes

A proper soak sets you up; your hands finish the job. Here’s how I run a clear, consistent process from the bucket to the buffer.

Prep and protect. Mask edges, character lines, and thin spots with high-quality tape. Put a couple layers on sharp creases. Edges are where clear is thinnest and where cutting is fastest.

Load and lay. Pull your pre-soaked sheet from the bucket, let it drip for two seconds, then lay it onto a damp block. For large flats, use a semi-rigid foam block; for curves, a soft interface. Press the sheet flat; no wrinkles.

Flood the field. Squeeze-bottle the panel until water sheets out. Your first passes are exploratory—listen for uniform shhh sound, not a squeak.

Crosshatch with intent. Sand in straight, overlapping strokes with light to moderate pressure—think the weight of your hand plus a little. Run a crosshatch pattern (north–south, then east–west) and stop every 6–8 passes to squeegee the panel with a clean rubber blade. The squeegee is your truth teller; it shows highs and lows in a second.

Check and change. Under a bright inspection light, look for uniform scratch pattern. If any orange peel islands remain after 1000 grit, don’t move up yet. It’s cheaper to spend three more minutes at 1000 than thirty at 1500 trying to remove what 1000 left behind.

Reset the field. Rinse your block and sheet in the rinse bucket. If the sheet still cuts evenly, keep it; if it chatters or drags, swap to a fresh one. Move to your next grit and repeat.

Finish clean. After your final 2500–3000 grit, wash the panel with clean water and a new microfiber. Let it dry before compounding. If you used soap, a quick wipe with a mild surface prep cleaner ensures your compound bites.

Pressure and patience are the two variables that ruin more finishes than any soak mistake. If you’re unsure, lighten up and add passes. Clear is finite; your goal is uniformity, not speed.

Actionable technique tips:

- Use a pencil guide coat on the clear at 1000 grit; stop when the last of the marks just disappear.

- If you must sand near an emblem or trim, cut a custom block from a firm sponge to focus pressure away from the edge.

- Keep a scrap of soaked 3000 grit in your pocket for spot-nibbing during polishing; it blends halos fast without re-soaking a full sheet.

Improper sanding between — Video Guide

If you’ve ever wondered why a finish feels gritty even after careful sanding, this short video breaks down the most common mistakes made between coats and how to fix them. It demonstrates proper grit progression, shows how to avoid dragging old slurry into a fresh surface, and emphasizes light pressure with consistent lubrication to get that silky, uniform feel before you polish.

Video source: Improper sanding between coats of finish- HOW TO AVOID IT!

220 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (25-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Refined medium-fine abrasive for final surface leveling on primed or sealed materials. Great for smooth touch-ups before finishing. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: How long should I soak wet/dry sandpaper before wet sanding clear coat?

A: For latex-backed silicon carbide sheets, 10–15 minutes at 800–1000 grit, 8–10 minutes at 1200–1500, and 3–5 minutes at 2000–3000 works well. Film or PSA discs should not be soaked; keep the panel wet instead.

Q: Can I over-soak wet sanding paper?

A: Hours-long soaks can soften the resin bond and shed grit prematurely on some papers. Short, intentional soaks (under 20 minutes) are safe for quality wet/dry sheets. If the paper feels mushy or the grit dusts off, it’s over-soaked or poor quality—replace it.

Q: Should I add soap to my soak water?

A: Yes—just a couple drops per quart. It reduces surface tension and helps the slurry move. Too much soap hides scratches and reduces feedback. Avoid oily additives or silicone; they contaminate surfaces and complicate polishing and refinishing.

Q: Can I reuse soaked sheets later?

A: You can store soaked sheets submerged in a sealed container for a day or two. Rinse them before reuse, and keep grits separated to prevent cross-contamination. If a sheet feels brittle, sheds grit, or shows deep embedded debris, discard it.

Q: What about using a DA sander—do I still need to soak anything?

A: No. Do not soak hook-and-loop or PSA discs. Keep a clean foam interface pad dry, mist the panel frequently, and wipe slurry often. Choose film-backed discs for a consistent DA scratch pattern and step through grits methodically before polishing.