Cross Sanding Panels with a Sanding Block

The first time you chase “flat” across a panel, it sneaks up on you. Early morning, bench light low and raking, coffee cooling by the vise. You sight across a tabletop you’ve glued up—a handsome mix of maple and walnut—certain you nailed the clamps this time. But you feel it before you see it: the slightest rise where two boards meet, a shallow dish near one corner that catches the light like a ripple on a still pond. It’s not bad, but it’s enough to make a finish telegraph every imperfection. You could reach for a random orbital and it would eventually get you there, but it’s like mowing a lawn in circles. There’s a faster, more controlled way to true a surface: cross sanding with a sanding block.

That’s when the shop gets quiet. I always grab a long, rigid block—mine’s just a straight, flat stick with cork on the bottom and PSA paper stuck on—pencil a light grid across the panel, and work at a crisp 45 degrees. The block bridges lows, the grit trims highs, and the pencil marks tell the truth. A few controlled passes, a flip in direction, and suddenly the surface starts talking back: even scratch lines, disappearing pencil, no shiny islands. This is where craft stops being guesswork and becomes process.

I’m Lucas Moreno, and I’ve leveled more panels than I can count—cabinet doors, benchtops, painted car panels, even fussy veneer. Cross sanding is still my go-to because it’s repeatable, fast, and brutally honest. Whether you’re dialing in a showpiece tabletop or unclogging orange peel on a clear coat, the right sanding block and a clean crosshatch pattern will get you flat without the guesswork. Let’s walk it step by step so you can feel that moment when a panel goes from “good” to perfectly true.

Quick Summary: Use a long, flat sanding block and 45° crosshatch passes to quickly level panels; read pencil marks and raking light, then finish with the grain.

The feel of flat: why cross-sanding works

Cross sanding works because it turns a messy, multidirectional problem into a controlled, geometric one. Instead of chasing scratches along the grain or swirling with a random orbital, you create two intersecting sets of straight, diagonal passes that reveal and remove high spots faster than any other hand method.

Here’s why it’s so effective:

- A long, rigid block bridges low areas rather than diving into them. That means you cut the highs first and protect the lows, which is exactly what “leveling” demands.

- The 45° angle to the grain prevents your block from tracking along softer earlywood, which can lead to scalloping; the diagonal path averages density differences across the board.

- Crosshatching creates a visible pattern. If pencil marks remain in islands after a pass, those are lows. When the pattern is uniform in both directions, the surface is flat.

- Diagonal scratches are easier to remove with final, with-the-grain strokes at a finer grit. You get both speed and a clean finish path.

Start every panel with a pencil grid—light, even marks every few inches. Use raking light from one side to exaggerate surface topography. With your block loaded, take long, overlapping strokes at roughly 45 degrees from left to right, using two hands and steady, even pressure. Keep your elbows locked and your wrists neutral; let your whole upper body guide the stroke. Rotate the panel or your stance and switch to the opposite 45° for the second pass. If your pencil tells you that only some areas are cutting, adjust pressure and stroke length until all marks begin to fade evenly.

Three quick cues tell you you’re on track: consistent scratch angles, no shiny low islands, and a “dry” sound that doesn’t pulse or chatter. That’s the feel of flat.

Gear and setup that make it effortless

Good results start with good setup. You don’t need fancy gear; you need the right basics tuned up properly.

Must-haves for leveling:

- A long, flat sanding block: 16–24 inches for tabletops; 10–12 inches for doors and drawer fronts. I like a straight stick of MDF with cork or neoprene on the face and PSA paper so it stays tight and dead flat.

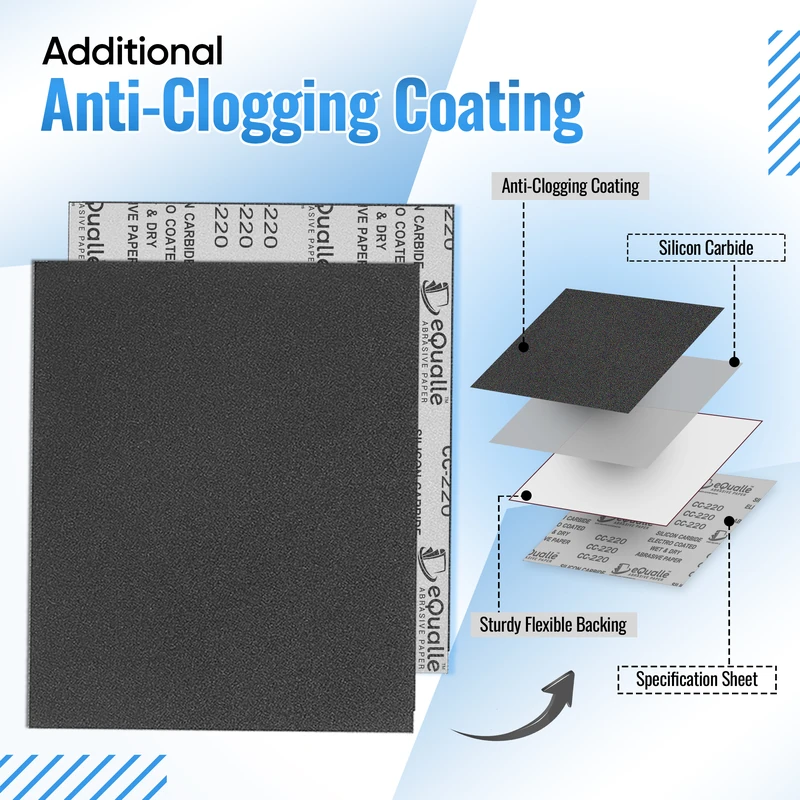

- Paper selection: Aluminum oxide for wood (80, 100, 120, 150, 180, 220). Silicon carbide for finishes, metals, and automotive clear (1000–2000+). Keep sheets fresh; dull paper rides the surface instead of cutting.

- Dust extraction and a brush: Vacuum often; dust clogs paper, slows cutting, and hides the truth your pencil’s trying to tell you.

- Raking light: A simple clamp light low to the side transforms what you can see. It’s like X-ray vision for low spots.

- Straightedge and pencil: A 24–36 inch straightedge and soft pencil for grid lines and quick checks.

Setup tips from the bench:

Lock the work. Clamp your panel to a non-slip surface or bench dogs. Movement ruins stroke consistency and creates uneven pressure.

Match block to task. Use a rigid block for leveling. Save soft foam blocks for final blending or contoured edges. If you’re leveling a painted or lacquered surface, add a thin, firm interface pad to reduce risk of digging.

Choose a starting grit that respects the material. For wood panels with minor misalignment, start at 100–120. For stubborn glue-line ridges, 80. For automotive clear leveling, 1000–1500.

Avoid “fingerprint pressure.” Always keep both hands on the block, with even spacing. Pressing with fingertips at the front edge will dish the surface and round edges quickly.

Refresh the paper often. If the block starts to skate or you see heat build-up, swap sheets. A fresh 120 will outpace a tired 80 every time.

Prep once, work smoothly, and your panel will tell you where to go next.

Pick the right sanding block for panels

Your block is your plane. Its size, stiffness, and face material determine how honestly it levels a surface. Choose a block that’s long enough to bridge problems and stiff enough to keep your strokes true.

What to consider:

- Length: For leveling, longer is better—aim for a block at least two-thirds the width of the narrowest dimension you’re leveling. On a 20-inch-wide tabletop, an 18–24 inch block sings. On a 12-inch door, a 10–12 inch block is plenty.

- Stiffness: Rigid blocks (wood or aluminum with cork/neoprene) are ideal for flattening. Semi-rigid foam with a firm face is good for blending transitions without telegraphing finger pressure. Fully flexible foam blocks are for curves and profiles, not for leveling flat panels.

- Face: Cork or 1/8-inch neoprene creates a micro-comply that grips paper and takes the sting out of grit without rolling into lows. Bare wood faces are aggressive but can telegraph slight imperfections; I reserve them for heavy stock removal with coarse grits.

- Paper attachment: PSA is my go-to for long blocks. It keeps the paper dead flat and won’t creep. Hook-and-loop is fast for shorter blocks but can round under hard pressure.

Material-specific picks:

- Wood panels: Rigid block with aluminum oxide paper. For wide tabletops, consider a shop-made beam—two layers of MDF laminated, jointed dead straight, with a cork face. Load full-width strips of PSA paper to avoid seams.

- Veneer or thin skins: Rigid block with fine grits (150–220). Think patience over pressure. Keep a sharp pencil grid; when the lines are almost gone, switch grits rather than pushing harder.

- Painted or clear-coated panels: Semi-rigid block with silicon carbide wet/dry paper. A thin, firm interface pad adds safety. Use water with a drop of dish soap as lube; it keeps paper cutting cool and clean.

Technique note: If you’re seeing persistent shiny islands after a full diagonal pass, don’t jump grits. Stay with the same grit, re-grid with pencil, and make a second diagonal pass at the opposing angle. The crosshatch pattern is your progress meter. According to a article this “X-pattern” is equally valued in finishing car panels because it reveals leveling more honestly than circular motion.

A well-chosen sanding block turns leveling from “hope” into a measured plan.

Cross passes: the step-by-step workflow

Here’s my shop-proven sequence for dialing in flat, fast. Adjust grits for wood vs. finish, but keep the structure the same.

- Assess and mark:

- Sight and tap with a straightedge. Note high glue lines, cupping, or dished corners.

- Pencil a light grid across the entire panel, including near edges.

- Choose your starting grit:

- Wood: 80 for obvious ridges; otherwise 100–120.

- Clear coats and paint: 1000–1500 (silicon carbide). Lubricate with water.

- First diagonal pass (45°):

- Load the sanding block with fresh paper.

- Stand square to the panel with feet shoulder-width apart.

- Take long strokes corner-to-corner, overlapping each pass by about one-third of the block’s width.

- Keep the block flat. Press with both hands—centered, not on the edges.

- Work the entire surface uniformly; don’t spot-sand yet.

- Check and re-grid:

- Vacuum dust and wipe. Under raking light, look for pencil islands (lows) and bare spots (highs already cut).

- If lows remain sprinkled rather than clustered, proceed; if you have a big low region, consider planing or scraping it closer to level before continuing to avoid dishing.

- Opposite diagonal pass (45°, the other way):

- Rotate your stance or the panel and repeat with the same grit.

- You should see the X-pattern even out, with fewer pencil islands.

- Grit progression and with-the-grain passes:

- Wood: Once the pencil marks are uniformly gone, move to 150, then 180–220. At each grit, do a light diagonal cross pass, then a final with-the-grain pass to align scratches with the wood.

- Clear coats: After leveling at 1000–1500, progress to 2000–3000 before buffing. Keep the block flat and wet; wipe slurry often to read the surface.

- Edge control:

- Ease edges with one light stroke by hand after leveling. Never let the block tip off the panel; that’s how rounding begins.

- If you must approach edges, set a “no-go” line 1/2 inch in; blend to the line, then hand-feather the last bit.

- Final inspection:

- Use raking light and touch. A flat surface will show uniform scratch direction, no shiny patches, and feel like a single plane under the palm.

- If you spot a localized low, pencil and make long, full-length strokes—resist the urge to spot-peck a defect.

Three pro tips:

- Guide coat for finishes: A mist of contrasting dry guide coat or powdered graphite on clear coats shows lows instantly.

- Timer discipline: Sand in sets of 10–12 strokes per section, then stop and check. Blind sanding is how you overdo it.

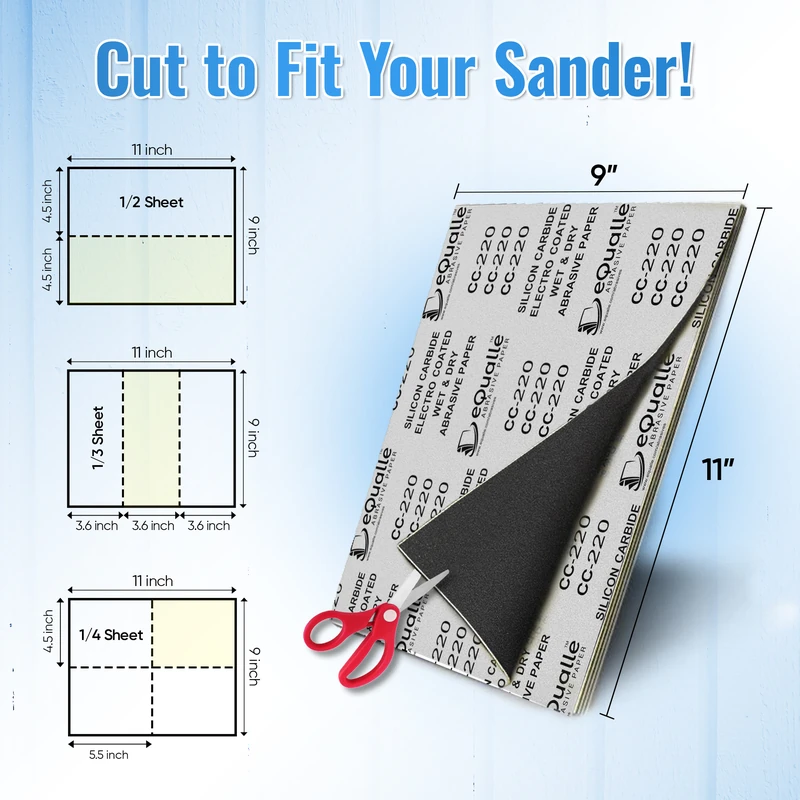

- Paper economy: Cut your paper into matched sets before you start. Swapping fast keeps you honest and consistent.

Follow the pattern, and you’ll be flattening in minutes, not hours.

Troubleshooting swirls and low spots

Even with a solid process, surfaces can misbehave. Here’s how I diagnose and fix the usual suspects.

Problem: Persistent shiny islands

- Diagnosis: Those shiny spots are lows that your block hasn’t bridged enough—or your pressure is uneven.

- Fix: Stay at the current grit. Re-grid and make another full set of cross passes with a longer, stiffer sanding block if available. Slow down and re-center your hands. If a low is broad, don’t chase it only in that spot; you’ll dish. Work the whole surface uniformly to bring the surrounding highs down.

Problem: Rounded edges

- Diagnosis: The block tipped or pressure drifted toward the edges.

- Fix: Set a 1/2 inch “safe border” with pencil and stop short on cross passes. Finish edges by hand with a shorter block, parallel to the edge, using two fingers only to guide, not press.

Problem: Swirl marks telegraph after finish

- Diagnosis: Over-reliance on random orbital early, or diagonal scratches left too coarse.

- Fix: Use the sanding block to level first. For wood, always finish with the grain at 180–220. For clear coats, bring the grit to at least 2000 before buffing. Under raking light, look for scratch direction; it should be consistent, not circular.

Problem: Paper clogs and burns

- Diagnosis: Resinous wood, old finish dust, or too much pressure.

- Fix: Vacuum frequently, lighten up, and switch to open-coat paper for wood. On clear coats, wet-sand with a drop of soap in the water to keep cutting cool and clean.

Problem: Veneer breakthrough panic

- Diagnosis: Edges of veneer are fragile; over-sanding at a coarse grit or tipping the block.

- Fix: On veneer, start no coarser than 150. Use a rigid sanding block and a light touch. Keep strokes long and the block fully supported on the panel. If you’re near a seam, reduce pressure and let the pencil grid guide your progress.

Actionable corrections to keep handy:

- Use a guide coat anytime you switch grits on finish work; it tells you immediately whether you’ve cleared previous scratches.

- Separate blocks for different grits to avoid grit contamination; a stray 80-grit granule left on a 180 block will ruin your day.

- When in doubt, lengthen the block. Longer means flatter.

- Take a final pass with fresh paper; dull paper burnishes lows and hides the truth.

Once you internalize the sound, feel, and sight of a flat panel, troubleshooting becomes second nature.

Are you using — Video Guide

If you’ve ever wondered whether your block is helping or hurting, this video-style breakdown is for you. It contrasts rigid, semi-rigid, flexible, and contoured sanding blocks, explaining which to use for flattening wide panels, which to grab for curved profiles, and how density affects pressure and risk at edges.

Video source: Are you using the wrong kind of sanding block? What you need to know...

240 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (25-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Smooth-cut abrasive for soft blending, de-nibbing, and light surface preparation before polishing or coating. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What angle should I use for cross sanding a panel?

A: Work at roughly 45 degrees to the grain for the first pass, then 45 degrees the other way to create an X-pattern. Finish with a light, with-the-grain pass at your final grit.

Q: How long should my sanding block be for leveling?

A: Aim for a block at least two-thirds the width of the narrowest dimension you’re flattening. For a 20-inch tabletop, 18–24 inches is excellent; for door panels around 12 inches, 10–12 inches works.

Q: What grits should I use on wood vs. clear coat?

A: Wood: start 80–120 for leveling, then 150, 180–220 to prep for finish. Clear coat: 1000–1500 to level, then 2000–3000 before buffing. Don’t jump grits too quickly; clear the previous scratches first.

Q: Can a random orbital sander replace cross sanding?

A: Not for leveling. A random orbital is great for scratch refinement and blending, but a long, rigid sanding block bridges lows and cuts highs faster and more honestly during leveling.

Q: How do I avoid rounding edges while sanding?

A: Keep the sanding block fully supported on the panel, stop 1/2 inch short of edges during cross passes, and finish edges by hand with light pressure. Never lead with a corner of the block.