Dustless Sanding and Negative Pressure Mastery

You can almost hear the sigh when the first pass of 120-grit levels a joint, the wall turning from patched to pristine. Then the moment breaks—fine powder blooms into the light, spiraling toward the hallway where a toddler naps and the HVAC returns hum. Anyone who has lived through a remodel knows that dust isn’t just a nuisance; it migrates through door gaps, rides thermal currents, and infiltrates electronics, textiles, and lungs. That’s why modern workflows pair dustless sanding at the tool with a properly engineered negative-pressure setup for the room. One contains the debris at its source; the other controls the air itself, ensuring any fugitive particles move in only one direction—out.

I’ve spent years designing finishing workflows where surface prep is treated like a process, not a chore. The difference between a clean, uniform finish and days of rework often comes down to the air path you design before the first sheet of paper touches the substrate. In a small bath, a tight stairwell, or an occupied living space, a negative-pressure containment turns chaos into control: the dust you don’t create is captured by a HEPA extractor through the sander; the dust you do create is drawn away from clean zones and expelled safely outdoors. Done right, you’ll protect occupants, accelerate cleanup, and maintain abrasive performance longer because discs and screens stay cleaner.

This guide will walk you through a rigorous, field-tested approach: planning the airflow math, selecting fans with adequate static-pressure capability, shoring up leak paths, and integrating dustless sanding systems into that airflow. I’ll detail failure modes too—backdrafting combustion appliances, collapsing poly sheeting, poor ducting choices—so you can recognize and prevent them. Whether you’re prepping hardwood floors, leveling drywall seams, or knocking down a primer nib on cabinetry, the same core principle applies: manage the dust path as carefully as you manage your scratch pattern.

Quick Summary: Build a sealed containment and maintain slight negative pressure with a proper exhaust fan and ducting, then integrate dustless sanding at the tool to capture what you create and control what escapes.

Why negative pressure stops dust

Negative pressure leverages a simple principle: air moves from high pressure to low pressure. If the work area is slightly lower than adjacent spaces, leakage flows inward through gaps instead of outward. That inward bias pulls stray dust into the containment where you can filter and exhaust it, rather than letting it migrate through the building.

Think in numbers. Pressure differential for residential remodels should generally fall between 2 and 5 Pascals (Pa) negative relative to adjacent spaces. More negative than roughly 8–10 Pa can risk backdrafting atmospherically vented combustion appliances nearby. In abatement and healthcare, -0.02 in. w.g. (~5 Pa) is a common target, and it’s a sound reference for dust control when managed prudently. Achieving and maintaining that delta depends on two variables: how tight your containment is (leakage area), and how much air your fan can move against the static pressure of filters and ducting.

A quick way to size airflow is by Air Changes per Hour (ACH). For a contained room of 12 ft × 15 ft × 8 ft (1,440 ft³), 6–10 ACH is typical for renovation dust control. That equates to 144–240 CFM of net exhaust. In reality, you need margin: long duct runs, multiple bends, and HEPA filters add static pressure that reduces fan output. A fan rated at 400–600 CFM free air but capable of 200–300 CFM at 0.5–1.0 in. w.g. is more reliable than a cheap axial box fan that collapses when you install filtration.

Plan makeup air deliberately. If you don’t define where replacement air enters, it will infiltrate through weak points—under baseboards, around light cans, and worst of all, through interstitial cavities that connect to the rest of the home. Create a controlled makeup opening (e.g., a masked doorway slit with a pleated prefilter) on the clean side so you know where air comes from. The exhaust duct should terminate outdoors, not into an attic or crawlspace, to avoid cross-contamination. Finally, instrument the setup: a simple differential manometer or Magnehelic gauge will confirm you’re maintaining the target pressure.

Integrating dustless sanding with airflow

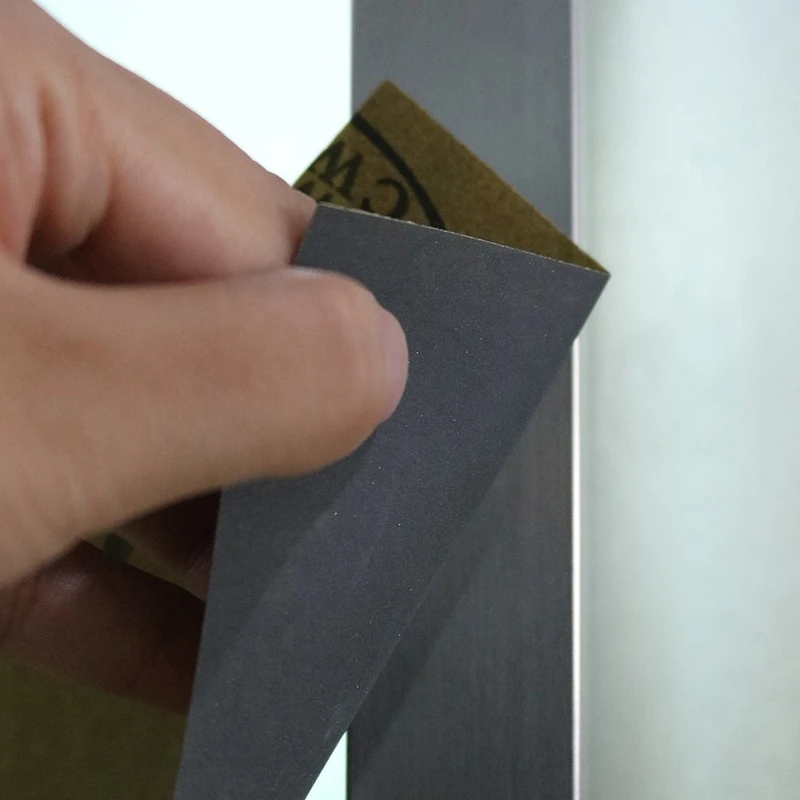

A negative-pressure enclosure is only half the strategy; capturing debris at the abrasive is the other half. Modern dustless sanding systems use high CFM and high suction at the pad, combined with multi-hole interface pads, perforated discs, and anti-static hoses to transport fines into a HEPA extractor. When the tool captures 80–95% of the generation at the source, the room exhaust has an easier job, filters last longer, and your abrasive stays cooler and sharper because the gullets don’t load.

On drywall, a dedicated drywall sander with a matched extractor maintains capture velocities at the pad even as surfaces become ultra-fine. On floors, a multi-stage approach works best: a drum or belt sander connected to a high-capacity dust collector, followed by a random orbital with HEPA extraction to refine the scratch pattern. For cabinetry and millwork, a compact 5" or 6" random orbital with a 150–200 CFM extractor and auto-start keeps airborne loading low without over-drying the work surface.

Workflow matters. Sequence your day so the biggest particulate generators occur first, while filters are fresh and airflow is strongest. Position the sander’s hose and the room exhaust so that both flows agree—never let the exhaust pull across your clean transfer area. If you do localized hand-sanding, set a portable downdraft panel or a shrouded hose pick-up to intercept fines.

According to a article, reducing dust at the source and controlling airflow paths dramatically improves livability during remodels. That’s consistent with field experience: source control reduces airborne residence time, and pressure control dictates direction of travel. Together, they prevent recirculation into HVAC systems and contamination of adjacent rooms.

Use appropriate filtration hierarchy. A prefilter (MERV 8–11) on the exhaust protects the HEPA final stage from coarse loading, extending service life. At the tool, a HEPA-rated extractor (99.97% at 0.3 µm) prevents re-emission through the machine. Keep hose runs as short and straight as possible, and use anti-static hoses and cuffs to prevent fines adhering to interior walls—static cling reduces effective CFM and sheds particles when jostled. The net result: stable capture, less cleanup, and better abrasive performance because the interface remains unclogged.

Sealing, ducting, and fan selection

Containment is a system. Start with envelope control, then match it with the right exhaust hardware. Poor seals force you to chase higher pressures and larger fans, which increases risk and noise without better outcomes.

Barriers and doors: Use 4–6 mil poly with reinforced tape seams on clean substrates; frame large openings with 1×3 battens or spring poles to avoid flutter. For entry, install a zipper door and add a weighted flap to minimize uncontrolled inflow. Seal baseboard gaps with painter’s tape to prevent undercut leakage jetting dust into adjacent flooring.

Exhaust path: Duct to the exterior through the shortest, straightest path. Smooth-wall duct (rigid or semi-rigid) has substantially lower friction than corrugated flex. Use 6–8 inch diameter duct to keep velocity moderate (~1,500–2,000 fpm), which helps transport dust without massive static penalties. Avoid more than two 90° bends; each bend can add the equivalent of 5–15 feet of straight run.

Fan type: Centrifugal (backward-inclined) and mixed-flow inline fans maintain CFM against static pressure far better than cheap axial fans. Look for published fan curves; you want the operating point (CFM versus static) to sit in the middle of the curve for stability. As a baseline, a 6–8 inch inline mixed-flow fan rated 400–700 CFM free air typically delivers ~200–350 CFM at 0.5–1.0 in. w.g. when paired with filters and ducting—sufficient for most single-room containments.

Filtration and noise: Place a MERV 8 prefilter before the fan to protect the wheel, and a HEPA final after the fan only if you must exhaust into a semi-enclosed area. Outdoor exhaust usually needs only a prefilter to protect neighbors from coarse debris. Use a simple weather hood with insect screen to keep critters out and reduce rain entry.

H3: Calculating the target airflow

- Room volume (ft³) = length × width × height.

- Target ACH = 6–10 for general sanding; 10–12 if occupants are sensitive.

- Required CFM = (Room volume × ACH) ÷ 60.

- Add 30–50% margin for filter loading and duct losses.

Actionable tips:

- Score seams before tape: Wipe surfaces with isopropyl alcohol or denatured alcohol where tape will adhere; dust-laden drywall or brick can cause premature seal failures that leak.

- Build a dedicated makeup air filter: Cut a 12×12 opening in a poly panel on the clean side and tape a pleated MERV 11 furnace filter over it; this controls inflow and prefilters incoming air.

- Stage a pressure relief: If your fan is oversized, add a second, smaller makeup opening with a magnetic cover you can peel back to fine-tune negative pressure without cycling the fan.

- Reduce duct losses: Use two 45° elbows instead of one 90° where you must turn; the effective resistance is lower, preserving CFM.

- Protect finishes: Place felt pads or sacrificial tape under poly floors to avoid imprinting patterns into soft flooring under sustained negative pressure and foot traffic.

Monitoring, safety, and cleanup

Even an elegant containment can drift out of spec as filters load and weather changes. Monitoring closes the loop. A differential pressure gauge (analog Magnehelic or digital manometer) across the barrier is the gold standard; aim for -2 to -5 Pa steady-state. If you lack a gauge, a smoke pencil test at the zipper and around penetrations can verify inward flow qualitatively. Some remodelers deploy low-cost environmental sensors to log PM2.5 outside the containment; a flat baseline confirms your control strategy.

Safety hinges on combustion awareness. Negative pressure can pull flue gases from atmospherically vented water heaters or furnaces. If such appliances are in the same pressure zone, either turn them off, isolate them outside the work zone, or keep the pressure modest and run continuous CO monitoring. Never exhaust into an attic, garage, or crawlspace—those are not final destinations. Direct outdoor discharge is the only responsible approach.

Make maintenance routine. Check prefilters daily; replace when visibly loaded or when the pressure differential increases beyond target to maintain flow. Clean the fan wheel when you see buildup—deposits disturb balance and reduce efficiency. At the tool, knock dust from discs frequently and rotate to fresh grits more often than you think; loaded abrasives cut hotter and shed particles that overtax your extractor. Use vacuum-assisted pad cleaning discs to extend disc life without embedding contaminants back into the surface.

Cleanup should be the quiet coda, not a second act. With dustless sanding plus negative pressure in place, your final pass is a HEPA vacuum of horizontal surfaces followed by damp wiping with a neutral cleaner or microfiber. Keep the exhaust running throughout cleanup and for 20–30 minutes afterward to clear residual aerosols. When you break containment, reverse the air path: cover the exhaust, open the makeup filter panel, and fold poly inward as you remove it so any clinging dust remains on the work side. Bag filters and poly inside the containment before carrying them out.

Testing DUSTLESS Sanding — Video Guide

A recent hands-on video puts a consumer dust-control kit through a realistic shop trial, stressing the balance between tool extraction and room exhaust. The host walks through setup, tests capture at the pad on typical substrates, and calls out where accessories and hose routing matter more than advertised CFM.

Video source: Testing DUSTLESS Sanding Tool - BUY or BUST?

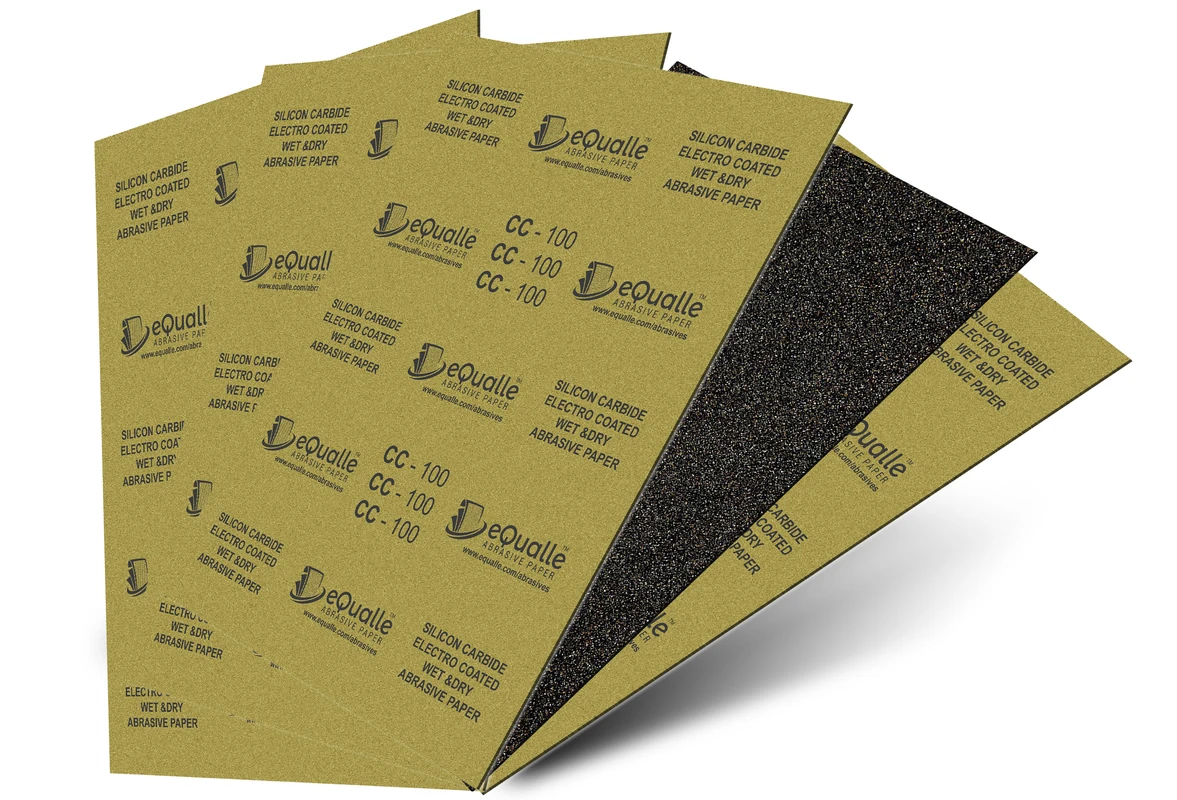

180 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (100-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Reliable grit for producing a uniform texture on wood, metal, or filler layers—often used before varnishing or applying topcoats. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: How much negative pressure is enough for residential sanding work

A: Aim for -2 to -5 Pascals relative to adjacent spaces. This is sufficient to bias airflow inward without risking combustion appliance backdrafting. Verify with a differential manometer and adjust makeup air to stay within range.

Q: Do I still need dustless sanding if I’ve set up negative pressure

A: Yes. Negative pressure controls direction, not generation. Dustless sanding captures most debris at the pad, reducing airborne load, protecting filters, and improving abrasive performance. Together they deliver clean results and faster cleanup.

Q: What size exhaust fan should I use for a typical room

A: Calculate the room volume and target 6–10 ACH. For a 1,440 ft³ room, that’s roughly 144–240 CFM net. Select a centrifugal or mixed-flow fan that can deliver 200–350 CFM at 0.5–1.0 in. w.g. after accounting for filters and ducting.

Q: How do I prevent dust from entering the rest of the home during door traffic

A: Install a zipper door with a weighted flap, place a sticky mat on the clean side, and create a filtered makeup opening so airflow stays inward even during entry/exit. Keep the exhaust running and minimize door-open time.

Q: Is venting into an attic or garage acceptable if I use HEPA filtration

A: No. Always exhaust outdoors. Intermediate spaces like attics and garages can redistribute dust and create secondary contamination. If you must filter heavily, use prefilters to protect your HEPA stage and still duct to the exterior.