Glass Sanding: Grit Progressions That Prevent Gouges

A few hours before guests arrived, I watched a friend trace a fingertip over the chipped rim of a vintage decanter—his grandmother’s. The room was quiet, the kind of quiet that magnifies small flaws into loud ones. The plan was simple: true the rim, restore the clarity, and bring back the smooth hand-feel that says this object is cared for. He had the abrasives, a spray bottle, a soft pad, and the patience to learn. What he didn’t have yet—what most people underestimate—is a deliberate grit progression that avoids planting damage deeper than you can later remove. Glass sanding looks deceptively simple. The physics behind it is not.

If you’ve ever watched a faint scratch linger through multiple steps, you’ve met the consequences of skipping grits. On wood or paint, you can sometimes cheat. On glass, cheating translates directly into subsurface damage and micro-cracking that only a full reset—or a costly replacement—can solve. The first passes set the ceiling for your final finish. Under poor technique, the ceiling drops with every “fast-forward” step you take. Get the sequence right, keep the surface cool and clean, and you’ll see the white haze collapse into transparency like frost meeting sunlight. That’s the moment you know your glass sanding workflow is working for you, not against you.

Quick Summary: Avoid deep scratches by using a tight, wet grit progression, controlled pressure, and rigorous inspection at each step; on glass, skipping grits multiplies subsurface damage and time.

Why grit progression governs scratch depth

Every abrasive step is a controlled act of damage. The art is confining that damage to a predictable depth and then replacing it with shallower, more uniform scratches until you can transition to polishing. On glass, the dominant failure mode under a grit particle is brittle fracture, not ductile plowing. That means individual grains can create micro-chips at the scratch root if you overload pressure, run dry, or use too coarse a grit to start. Those chips scatter light—even after you’ve “polished”—because you’ve polished the hills but left canyons beneath.

Scratch depth scales with grain size, shape, and load. A 120-grit silicon carbide sheet has average particles roughly 125 microns, easily cutting scratch valleys tens of microns deep under excessive pressure. Going straight from 120 to 400 won’t bridge that gap efficiently; you’ll either spend ages trying to erase 120-grit trenches with grains three to four times smaller, or you’ll accept that those valleys will telegraph through to your final gloss.

Progressions that work treat scratch depth like a taper. Each step removes the previous peak-to-valley amplitude by roughly 30–50% more than the previous left behind. On glass, this often means a ladder like 120/180/240/320/400/600/800/1200 before shifting to pre-polish (e.g., 1500–3000) and then cerium oxide. The exact starting grit depends on the defect depth, but the intervals should be tight (not more than 1.5× jumps in particle size), and every step should fully replace the scratch pattern.

Running wet is non-negotiable: water plus a drop of surfactant lowers friction, carries swarf, and prevents heat-driven micro-cracking. Combine that with light, even pressure and consistent, overlapping passes. When you respect the sequence, you decide the maximum damage depth from the outset—and you keep it shrinking on schedule.

Workflow specifics for glass sanding and crystal

Sanding glass carries unique constraints: low fracture toughness, high hardness, and a ruthless habit of revealing every mistake at the polishing stage. Glass sanding favors abrasives and workflows designed to manage brittle materials.

- Abrasive selection: Silicon carbide (SiC) is the default for wet work on glass; it fractures into sharp edges and cuts cool. Diamond abrasives are excellent for controlled material removal on thick or tempered pieces, but they must be handled gently—especially at coarse grits—to avoid chip-outs. Avoid aluminum oxide as it tends to dull rather than fracture, increasing heat.

- Backing interface: Use a compliant but supportive pad. Too soft and you’ll round edges or dish a rim; too hard and you’ll print deep scratches. For flats, a medium-hard rubber or urethane backing maintains contact without introducing pressure spikes. For edges, consider a denser felt or hard pad and work with the face just kissing the arris at a shallow angle.

- Lubrication: Always wet-sand. Add a drop of dish soap or a proper surfactant to water to break surface tension and stabilize slurry. Refresh the fluid often; stale slurry recuts old debris and seeds random scratches.

- Motion and mapping: Cross-hatch each grit at 45° to the previous pattern. On circular work, let the orbit or rotation do the heavy lifting but introduce a slow, deliberate feed to avoid dwell marks. Finish each grit by removing all visible scratches that run in the previous direction.

Typical progression for a chipped rim on soda-lime glass starts at 120 or 180 if chip depth exceeds ~0.2 mm. For light scuffs, start at 400–600. Move in 1–2 grit steps (e.g., 180 to 240 to 320 to 400, etc.). Verify each transition under strong, oblique light before advancing.

Crystal (lead glass) can feel “buttery” and may cut faster, but it still demands strict control. Keep pressures low, speeds conservative, and edges protected by masking if you must maintain geometry. Done right, the payoff is obvious: clarity without distortion, and a tactile smoothness that invites use, not fear.

Choose starting grit with intent

The wrong starting grit is the root of most finishing failures. Too coarse, and you dig craters you’ll spend hours erasing. Too fine, and you burnish high spots while leaving defects intact, forcing rework. Choosing correctly is a measurement exercise, not a guess.

Assess defect depth. Use raking light and a 10–20× loupe to quantify scratch width; width roughly scales with depth. If a scratch is visible at arm’s length in diffuse light, you’re typically above what 800–1200 grit can erase efficiently. A simple test coupon—a sacrificial piece of similar glass—helps you calibrate removal rates at various grits and pressures. Remember that glass doesn’t telegraph like wood; subsurface fractures are invisible until the final polish, so you must manage risk up front.

For flat panes, mark your target area with a wax pencil, then lap with your candidate starting grit for 30–60 seconds. Clean, dry, and inspect. If the defect is barely touched, drop one grit. If new scratches are grossly deeper than surrounding damage, you started too coarse. Repeat until you identify the coarsest grit that reliably levels the defect in reasonable time without introducing outsized valleys.

Actionable tips:

- Begin one step finer than your first instinct on glass; coarsen only if removal is unacceptably slow.

- If you can’t fully remove the previous scratch pattern within 2–3 minutes on a small area (50–100 mm), your grit jump is too large.

- Use a wet, lightly soapy solution and refresh it every 60–90 seconds to prevent slurry-induced random scratches.

- Mark each stage’s scratch direction; don’t advance until all marks from the previous direction are gone.

- For edges, bevel slightly with your starting grit to eliminate sharp arrises that tend to chip under lateral load.

Sanding workflows are well-studied in craft and industry. According to a article, a deliberate starting grit choice sets you up to remove damage—not compound it—and reduces total time to clarity.

Pressure, lubrication, and pad control

Even perfect grit sequencing fails under poor force control. Glass punishes heavy hands with micro-chipping that rides along until the end. Your three control levers are normal force, lubrication, and backing pad stiffness.

- Pressure: Aim for just enough pressure to keep the abrasive cutting without stalling—typically the weight of the tool plus a light hand. If water is bow-waving from the contact zone, you’re too heavy. Excess pressure drives abrasive grains below the elastic limit, initiating radial cracks at scratch roots. Those cracks are what you later see as persistent haze.

- Lubrication and temperature: Heat is the silent spoiler. Keep the surface cool with a steady film of water; add a drop of surfactant to maintain wetting. If the work warms to the touch, stop, flush slurry, and resume after a brief cool-down. On machine sanders, run at moderate speed: 2,000–6,000 OPM for random orbits, low RPM for rotary with a soft interface pad. Glass is unforgiving if you stall a pad or dwell; keep the pad moving, and never lean on edges.

- Pad and interface: Harder pads cut flatter but print scratches deeper; softer pads contour better but can round edges and “float” over lows. Match pad to geometry. For flat panels, use medium-hard foam or rubber. For slight curves, a medium pad plus a thin film interface (1–3 mm) balances support and conformity. For polishing, switch to felt or dedicated polishing foam.

Technique details matter: Overlap passes by 30–50%, and spend consistent time across the area. Use a metronome-like motion to avoid dwell spots. Rinse and wipe clean between grits—carryover grit is a common cause of “mystery” scratches. If contamination strikes, drop back one grit, reestablish uniformity, and only then proceed. When you treat lubrication and pressure as part of the recipe, not afterthoughts, your grit progression can do its job.

Validate, then polish to optical clarity

Advancing grits without proof is how deep scratches survive to the end. Validation is fast and simple with the right habit stack.

- Dry inspection: After each grit, rinse thoroughly, squeegee, and inspect under raking light from multiple angles. Drying removes specular glare and lets true scratch structure appear. A loupe or low-power microscope makes this conclusive—look for any lines aligned to the previous grit direction; if any remain, you’re not done.

- Map and segment: For larger surfaces, divide the area into quadrants. Track time in each quadrant per grit to maintain uniformity. Skipping time is a form of skipping grit.

- Clean transitions: Change water, wipe the surface, and use fresh abrasive or a clean section before moving up. Never assume spent sheets are safer; dull grains can load, heat, and fracture glass unpredictably.

When your surface is uniformly abraded at 1200–3000 grit with no directional ghosts, you’re ready to polish. Cerium oxide is the glass standard. Mix a slurry to the consistency of thin cream and apply with a dedicated felt or polishing foam pad at low speed. Keep it wet. The goal is chemical-mechanical polishing: slight heat and mild pH interaction plus gentle mechanical action to collapse the final micro-topography. Avoid edge pressure—this is where people “polish in” distortions.

Polishing is not a license to fix deep mechanical damage. If you see persistent haze under oblique light, step back one abrasive stage and relevel. A good rule: when in doubt, back up one grit rather than leaning longer at the current step. That restraint avoids both overheating and over-thinning. Finish with a thorough clean, then a final pass with clean water to remove residual cerium bloom. If you’ve honored each validation gate, you’ll see true clarity, not just shine.

How To Sand — Video Guide

A recent tutorial titled “How To Sand And Polish A Glass Bottle” walks through the end-to-end process of truing a bottle edge and refining it to a clear polish. It emphasizes how time-consuming hand work can be and why patience with each grit matters on curved glass.

Video source: How To Sand And Polish A Glass Bottle

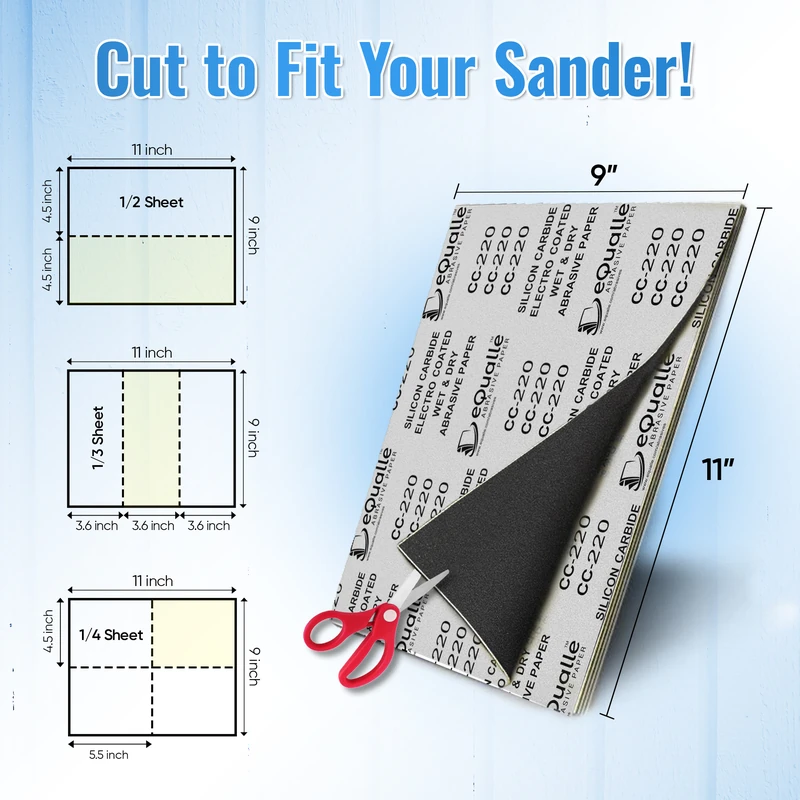

150 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (25-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Versatile medium grit that transitions from shaping to smoothing. Works well between coats of finish or for preparing even surfaces prior to paint. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: How many grits should I use for glass sanding?

A: Plan on 6–9 abrasive steps from your starting grit to pre-polish (e.g., 180 → 240 → 320 → 400 → 600 → 800 → 1200 → 2000/3000), followed by cerium oxide polish. Tight steps replace scratch depth predictably and prevent deep valleys from persisting.

Q: Can I skip from 400 to 1200 if I’m in a hurry?

A: Not on glass. The 400-grit valleys are too deep for 1200 to remove efficiently; you’ll either leave residual trenches or overheat the surface trying. Use 600 and 800 (or 1000) as intermediates to bridge the depth.

Q: Should I use diamond abrasives for all stages?

A: Use diamond for initial shaping or heavy defect removal when you need fast, controlled cutting—especially on thick glass. Transition to silicon carbide for mid and fine steps to manage fracture risk and heat, then polish with cerium oxide.

Q: How do I know I’ve fully removed a previous grit’s scratches?

A: Cross-hatch each stage and inspect dry under raking light. If any lines aligned to the previous direction remain, continue at the current grit. A 10–20× loupe makes this determination unambiguous.

Q: What’s the best way to avoid chipping at edges?

A: Bevel the edge slightly at your starting grit, use a firmer backing pad to support the arris, keep pressure minimal, and approach edges tangentially rather than pushing into them. Always keep the surface wet and the pad moving.