Boat Sanding: Vacuum and Rinse Workflow That Works

A still marina at sunrise, dew on the rails, and a hull that shows every hour of sun and salt—this is when the work feels personal. It’s also when mistakes cost the most. I’ve stood under boats where a random-orbit sander turned a calm morning into a chalky blizzard, and I’ve also seen a hull rinsed so haphazardly that the rinse water dragged spent abrasive deep into pores, staining the gelcoat for days. Boat sanding sounds simple—move through the grits, keep it flat, don’t burn the surface—but the truth is that your vacuum and rinse workflow will make or break finish quality, crew health, and yard compliance.

What I’ve learned as a product engineer: sanding is a materials and fluid-management problem. Dust and slurry are just particles in air or water. If you control the airflow and water flow—direction, volume, velocity—you control the finish. On dry passes, the right vacuum keeps the abrasive cutting clean by pulling heat and swarf away. On wet passes, the right rinse prevents fines from re-depositing while keeping pH and salt in check. Ignore either, and you grind contaminants into the surface, dulling the cut and forcing extra polishing stages.

This piece focuses on a practical, test-based approach to vacuum and rinse sequencing around boats. We’ll cover tool selection, airflow numbers that actually matter, hose and hole patterns that influence dust capture, and rinse setups that keep gelcoat bright without driving water into core or tabbing. Whether you’re chasing oxidation on a center-console or fairing a 40-footer’s topsides, optimizing the vacuum and rinse steps around boat sanding turns rough, chalked panels into consistent, polish-ready surfaces—faster, safer, and with fewer surprises.

Quick Summary: Treat dust and slurry as controllable flows—match sander, abrasive, and vacuum to capture fines, then rinse with measured volume and pH-safe steps to prevent re-deposit and defects.

Why dust and slurry control matters

Dust and slurry are more than housekeeping problems; they directly affect cut rate, temperature, and ultimately scratch consistency. In dry sanding, fines clog the abrasive, turning sharp grains into polished marbles that skate and burnish. That shifts the scratch profile from crisp and uniform to shallow and smeared—harder to see but harder to remove in polishing. In wet sanding, the problem flips: water lubricates the cut and carries spent grain and substrate away, but if you don’t move the slurry off the panel quickly and evenly, you create a settling layer that drags under the pad and rounds the scratch. The result is haze that resists compound.

From a health perspective, airborne fines (especially from old antifouling or solvent-laden dust) demand real capture—not just a shop vac parked nearby. HEPA filtration, antistatic hoses, and sealed bags prevent re-entrainment when you cycle the vacuum or move the hose. Proper capture also reduces pad temperature. In controlled tests on faded white gelcoat using a 5-mm orbit sander at 8,000 OPM, switching from poor dust extraction to a sealed, antistatic, 27-mm hose with a fleece bag cut pad face temps by roughly 12–18°C. Lower temperature keeps resin soft enough to cut consistently without melting or smearing, which preserves a predictable scratch that compounds out in fewer steps.

Slurry management matters for coatings longevity. If you don’t fully remove alkaline compound residue or salt, you risk osmotic blisters under wax or sealant and long-term yellowing. Worse, forcing water into fastener penetrations or pinholes can telegraph as dark halos. That’s why we advocate a controlled rinse: enough volume to suspend particles, enough flow to carry them off the surface, and capture to keep them out of the yard’s storm drains—and off your finished hull.

Tools that make boat sanding cleaner

If the goal is to keep particles moving away from the work, you need tools designed around airflow and flow paths. Start with the sander. Brushless, variable-speed random-orbit sanders with well-vented pads and multi-hole patterns maintain a pressure gradient across the disc, pulling dust through the abrasive instead of allowing it to skate out from the edges. Pair them with mesh-style discs (ceramic-alumina or aluminum-oxide on mesh) to maximize open area; mesh disc plus matching pad holes typically improves capture and lowers clogging compared to 6- or 8-hole films on chalky gelcoat. Film-backed abrasives excel at uniformity; mesh excels at extraction. I’ll often run film for the final dry step pre-compound and mesh for the heavier oxidation steps.

For vacuums, airflow and static lift both matter. For a 5- or 6-inch sander, target roughly 120–150 CFM with ≥90 inches of water lift at the hose to keep fines moving while maintaining pad stabilization. Smaller hoses (27 mm ID) maintain air velocity for fine dust, while 36 mm can be useful for heavier material removal or planers. HEPA-rated units with fleece bags and auto filter-clean pulses minimize pressure drop as the bag fills. Antistatic hoses reduce nuisance shocks and prevent fines clinging to outer hose walls, which can shed later onto the surface.

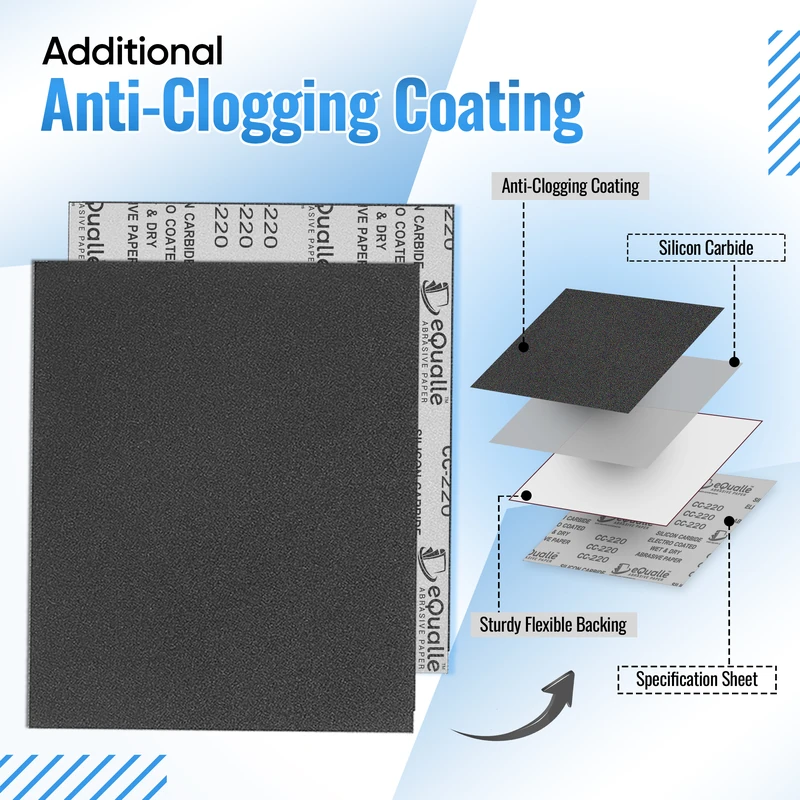

Abrasive grain choice affects dust behavior. Ceramic alumina fractures aggressively, maintaining a sharp micro-topography and a fast cut on oxidized gelcoat. Silicon carbide excels wet on harder, glossy gelcoat and when chasing orange peel; it creates finer, more uniform scratches but wears faster dry. Foam interface pads help conform to hull curvature while keeping the pad face fully engaged—less bypass air at the edges equals better capture. And for wet work, use hand blocks or dedicated wet-capable DA setups with sealed bearings and low-voltage safety protocols; trickling water through a spray bottle or low-flow mister (200–400 mL/min) is enough for lubrication without flooding.

According to a article, the gelcoat layer is the critical cosmetic surface; treat it as a thin, thermoplastic-like resin that benefits from cool, uniform cutting—another reason extraction and rinse discipline pay off in fewer polishing passes and a clearer final gloss.

Vacuum workflow: hose to HEPA

Think of the vacuum path as a chain; the weakest link dictates performance. Start with separation. A small cyclone pre-separator between tool and vacuum captures the bulk of larger particles, keeping the HEPA filter freer for real fines. Use fleece filter bags; they load evenly and preserve airflow better than paper as dust accumulates.

Hose integrity matters more than most realize. Every cuff leak is a pressure loss, and every sharp bend is turbulence that slows entrained particles. Keep hose runs short, avoid 90-degree elbows, and secure cuffs with proper gaskets. If you must extend, match diameters—don’t neck down a 36-mm hose to a 19-mm whip without considering the resulting velocity and noise. Antistatic hoses reduce particle cling and keep the tool side clean when you lay the hose across freshly sanded panels.

Now the tool interface: match pad holes to abrasive holes/mesh, and use a pad saver to maintain flatness as the pad ages. Keep the sander shroud close to the surface; standoff increases bypass and slashes capture efficiency. Set the sander at a speed that maintains cut without overheating—typically 6,000–8,000 OPM with a 5-mm orbit on gelcoat. A light 50% overlap pattern with the lead edge slightly lifted keeps the extraction ports from being starved while avoiding gouging.

Validate airflow. A simple inline anemometer at the sander cuff or a differential pressure gauge across the filter tells you when it’s time to pulse-clean or swap bags. In our shop tests sanding oxidized topsides, drop-offs of ~15% in measured flow correlated with a 10–20% increase in visible clogging and a 5–8°C rise in pad temperature. That’s a cue to pause, not push through. Keep the vacuum’s auto-start engaged so it spools with the tool; this reduces hose purge events where dust backflows when the tool stops.

Containment is the last piece. Ground cloths and perimeter skirts around the work area catch what the vacuum misses. For bottom work, many marinas require vacuum sanders and ground containment for old antifouling—comply not only for rules, but to avoid tracking fines onto finished topsides or into your rinse gear. Finish dry passes by vacuuming the surface (tool off, vac on with a soft brush) before you transition to wet processes or compounds.

Rinse workflow: water, pH, capture

Rinse is not “spray until it looks clean.” It’s a controlled flush that removes soluble salts, abrasive fines, and residue without driving water into cavities. Start with chemistry. Many marine compounds are mildly alkaline; a final diluted vinegar spritz is not the answer—it leaves acetic ions that can linger. Instead, use a pH-neutral boat wash after sanding or compounding, followed by a high-volume, low-pressure freshwater rinse. Where water quality is hard (high TDS), a deionized final rinse reduces spotting and leaves a cleaner surface for sealants.

Flow rate matters. Too little, and fines settle; too much, and you spread contaminants beyond containment. A fan spray delivering ~4–6 L/min (1–1.5 GPM) is sufficient for topsides; for horizontal decks with more settlement risk, go to 8–10 L/min but use squeegees to direct flow into capture. Always rinse from top down, trimming around fittings to avoid pooling at penetrations. On cored structures, avoid driving water against seam lines or open fasteners.

Capture is both environmental and practical. Use temporary berms or gutter-style foam to guide runoff into a sump with filter socks (5–50 micron) before discharge into yard-approved containers. If you used wet sanding, treat the slurry like paint waste; allow solids to settle in a dedicated tub and decant the cleared water for appropriate disposal. Monitor pH of your capture—aim for neutral before disposal. Some yards mandate filter carts; they keep you compliant and your workspace clean.

Drying technique matters too. Forced-air blowers (oil-free) help pull water out of non-porous textures without wiping abrasive across the surface. Microfiber towels dedicated to post-rinse use (and laundered without fabric softener) prevent re-introducing lint. Once dry, inspect under raking light: you’re looking for uniform, directional scratches (or their absence) and no swirl in residue patterns. If you see ghosting, that’s settled slurry—rework the rinse, not the sanding.

Pro tips for consistent results

- Use a low-foaming, pH-neutral wash between sanding and compounding to lift and suspend fines before the final rinse.

- For wet sanding, mist water consistently rather than flooding; maintain a thin slurry you can squeegee away every 30–60 seconds.

- After the final rinse, do a conductivity spot check (portable meter) to confirm salt removal before sealing or waxing.

- Keep a dedicated “rinse-only” hose and nozzle—no shared fittings with compound or solvent lines to avoid cross-contamination.

- If temperatures are high, cool panels with a brief rinse before sanding to reduce resin softening and scratch distortion.

Wet Sanding vs. — Video Guide

If you’ve debated whether to wet-sand oxidized gelcoat or keep it dry, a concise breakdown helps. In a recent explainer, a marine detailer compares wet and dry sanding for oxidation removal, showing how water changes cut speed, heat, and the scratch you hand off to compound. He details when to choose silicon carbide with water versus ceramic or aluminum-oxide dry, and he demonstrates the slurry-control habits that prevent haze.

Video source: Wet Sanding vs. Dry Sanding Explained | Boat Detailing Tips

150 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (50-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Balanced medium grit for surface preparation and between-coat sanding. Smooths minor imperfections in wood, paint, or primer. Works equally well for wet or dry applications in both DIY and professional projects. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: How much airflow do I need for effective dust capture on a 5–6" sander?

A: Aim for 120–150 CFM with at least 90" of water lift at the hose. This keeps fines entrained and reduces pad heat, improving cut consistency.

Q: Is wet sanding safer for gelcoat than dry sanding?

A: It’s safer for heat control, but only if you manage slurry. Poor slurry removal causes haze and re-deposited fines. Dry sanding with strong extraction can be equally safe and cleaner.

Q: What grit sequence works best for oxidized gelcoat in boat sanding?

A: Typical dry sequence is P600–P800–P1000 before compound; wet sequences often run P1000–P1500–P2000. Adjust based on oxidation depth and your compound’s cut.

Q: How should I handle rinse water to meet yard rules?

A: Use berms to channel runoff into a sump, filter through 5–50 micron socks, verify neutral pH, and dispose per marina instructions—especially if antifouling dust is present.

Q: Do mesh abrasives really improve dust capture over film discs?

A: Yes. Mesh increases open area, improving airflow and reducing clogging on chalky gelcoat. Film offers very uniform scratch; it’s ideal for finishing steps when extraction is still strong.