Hand sanding vs block: when each method wins

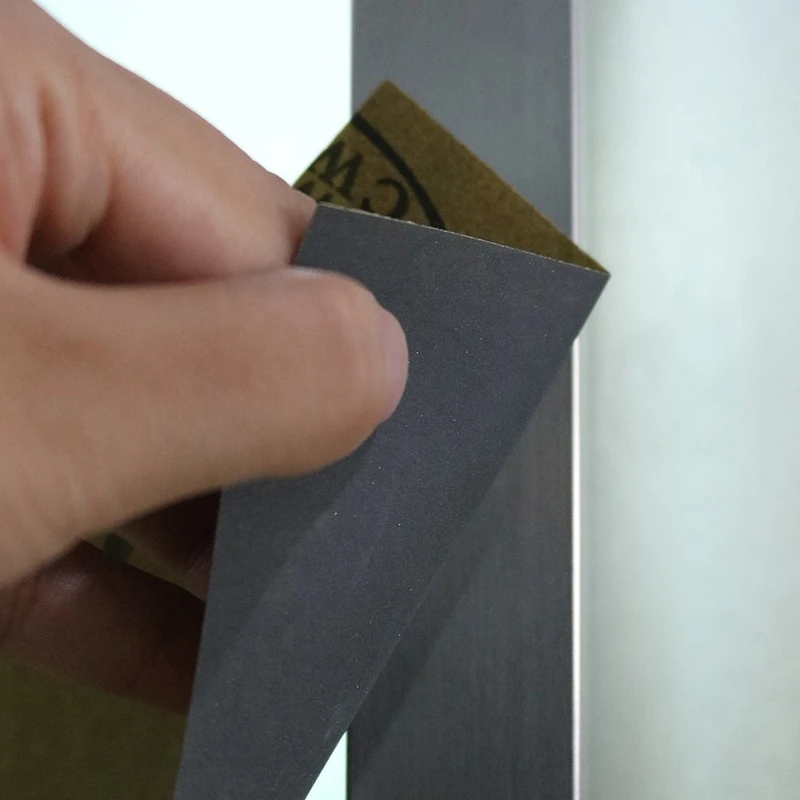

The quiet rhythm of sanding is one of the most honest sounds in making. Picture a Saturday afternoon: sunlight across the bench, a project that matters—maybe the oak table your family eats at, a guitar body you’ve been shaping for months, or a door panel you’re finally prepping for paint. You feel the surface more than you see it. The paper whispers over high spots, snags a little on a nick you missed. Instinct nudges the next move—do you keep the tactile connection of hand sanding, or pick up the block to force the surface true?

This small decision has big consequences. Bare-handed, you can follow a curve as if you drew it; you can nestle into recesses, kiss edges lightly, and blend a repair so it disappears. A block, though, brings geometry to the conversation: straight, flat, square. It ignores the soft valleys of your fingers and presses the peaks down with authority, speeding up work and preventing dips and waves. Learning when to trust your fingertips and when to let a block lead is the difference between “pretty good” and “why does this look so professional?”

We’ll walk through exactly that—how to choose your method based on the surface in front of you, the finish you’re aiming for, and the time you have. Along the way, we’ll blend craft intuition with practical rules, give you grip-and-grit tactics that save hours, and show how a few simple checks prevent rework. Whether you’re smoothing a cutting board, fairing body filler, or leveling primer, you’ll leave confident and calm about when—and why—to reach for hand sanding or a block.

Quick Summary: Use a block for flatness and speed on broad planes; choose hand sanding to follow curves, blend edges, and reach detailed contours—then let technique, grits, and guide coats tie it all together.

Shape, surface, and the rule of flatness

Start by reading the surface. Is it supposed to be flat, straight, and true—like a tabletop, cabinet door, hardwood threshold, or body panel? Or is it intentionally curved—like a guitar neck, a rounded chair leg, or the recess behind a door handle? That single question guides most sanding choices.

Blocks exist to create and protect flatness. Your hand, even with even pressure, has a natural softness. Pressing with fingers telegraphs their shape to the work, especially on softer materials. That soft contact can inadvertently hollow a spot as you chase a mark. A sanding block—rigid or semi-rigid—spans across highs and lows and knocks down peaks first, preserving geometry and leveling faster. On large panels or long edges, a longer block or “longboard” gives you a built-in straightedge.

On the flip side, there are places where a block is a mismatch. Inside curves, small fillets, sculpted bevels, and tight transitions benefit from the way your hand can conform. With light pressure and a flexible interface (like a foam pad or folded paper), hand sanding will blend a radius, soften a chamfer, or feather a repair without digging corners. This is especially helpful when you need to “feel” the progress—like smoothing a carved handle or easing an edge that will be touched frequently.

To decide quickly:

- If the surface needs to be flat or straight, reach for a block first.

- If the surface is curved or detail-rich, start with hand sanding and a soft backer.

- If you’re not sure, mark with a pencil guide coat and do a dozen strokes both ways. The block will leave clear, even scratch patterns across highs; your hand will whisper into recesses. The pattern tells the truth.

Remember: you can switch methods as the surface evolves. It’s normal to rough-shape by hand, then refine with a block, then return to hand work for final blending.

When hand sanding beats the block

Many surfaces are designed to be touched, not measured, and that’s where hand sanding shines. The goal isn’t mechanical flatness—it’s continuity and comfort.

Typical winners for hand sanding:

- Inside curves and coves: Think of the underside of a banister, an acoustic guitar neck transition, or the concave recess around a car door handle. A rigid block skips and stalls; your fingers, supported by a foam pad or a rolled piece of paper, ride the curve smoothly.

- Feathering edges: When removing a dust nib in finish or blending a chip repair on paint or varnish, bare-handed touch lets you control pressure so you don’t telegraph the edge. You can “float” the abrasive so it fades outward.

- Small, sticky geometries: Mullions, molding details, and chamfers respond well to a folded abrasive supported by a soft backing. You can fold to a custom profile on the fly.

- Final edge breaks: Softening a sharp edge to prevent chipping or finish failure takes just a couple of light, even passes by hand. A block can overdo it in a heartbeat.

Practical technique makes hand sanding precise, not sloppy:

- Back up your paper. Wrap it around a foam interface pad, a piece of leather, or even a pencil or dowel for small radii. This prevents finger grooves and distributes pressure without losing conformance.

- Use light, repeatable strokes. Think of polishing, not grinding. Count strokes on symmetrical parts to keep things even.

- Switch grits deliberately. For shaping curves, 120–150 gets you there without deep scratches; 180–220 refines; 320–400 is for pre-finish smoothing. On metal, stop around 220–320 before primer unless the system specifies finer.

- Feel, then look. Close your eyes, glide your fingertips across the area, then open and cross-check under raking light. Your skin will pick up a flat spot or ridge before your eyes do.

Finally, know when to bail out. If an inside curve is lumpy after a minute, make a mini-block to match its shape. A scrap of foam, a rubber eraser, or a carved cork makes a perfect custom tool, combining hand sensitivity with guided flatness on the curve.

Block sanding for speed and precision

If you need to level, flatten, or fair a broad area, block sanding is your ally. Blocks come in flavors—rigid acrylic or aluminum for dead-flat work, cork or rubber for a touch of flex, and foam-faced blocks for subtle curves. Long blocks distribute pressure across a wider footprint, naturally averaging out small highs and lows.

Use a block whenever you:

- Level seams, joints, or repairs on wood or filler.

- Sand end grain to keep it flush with adjacent fibers.

- True up edges and long faces that must be straight—like cabinet doors or rocket fins.

- Fair body filler and primer on auto panels for paint.

Technique turns a block into a precision instrument:

- Crosshatch your strokes. Sand in a shallow X-pattern—say 45° across the surface, then 45° the other way. This avoids grooves and reveals high/low patterns clearly.

- Apply even, modest pressure. Let the abrasive cut; pushing harder only clogs paper and digs corners.

- Use a guide coat. Lightly dust the surface with a contrasting dry pigment or marker. As you sand, the remaining color shows low spots instantly.

- Keep the block fully supported. Avoid tipping at edges; instead, hang the block over the edge slightly and take strokes that don’t roll onto the arris.

According to a article, builders comparing techniques for thin fins found that blocks help keep faces flat and edges crisp, while selective hand work refines the final profile—an insight that maps neatly onto woodworking and bodywork too.

Choosing the right block matters:

- Rigid (acrylic/aluminum): Best for flattening panels and edges. Shows you the truth about flatness and quickly highlights highs.

- Semi-rigid (cork/rubber): Adds forgiveness for slight camber or gentle curves while maintaining fairness.

- Foam-faced or interface-pad blocks: Ideal for compound curves or to prevent “print-through” on softer materials like primer or end grain.

- Longboard styles: Speed up leveling and improve straightness on long surfaces; great for doors, tabletops, and quarter panels.

Swap papers when they dull. A sharp 150 grit on a block beats a tired 120 every time—and clogging causes scratches you’ll have to chase later. Keep a scrap piece handy to clean paper (or use a crepe rubber cleaner), and if you see dust smearing instead of cutting, change sheets.

Grits, patterns, and pressure control

Grit choice and stroke pattern matter as much as the tool in your hand. A simple plan saves time and prevents rework.

A reliable sequence:

- For shaping and leveling: 80–120 grit on a block for wood or filler. On thin veneers or fragile parts, start at 120.

- For refinement before finishing: 150–220 grit on wood; 180–320 on primer or body filler depending on your coating system.

- For pre-finish smoothing or between coats: 320–400 for wood finishes; 400–600 for automotive primers and clears as specified.

Patterns and checks:

- Crosshatch on planes, follow-the-form on curves. Your scratch pattern should reinforce the geometry you want.

- Pencil lines or a powder guide coat reveal progress instantly. Don’t guess—mark lightly, sand until the marks just disappear, and stop.

- Raking light is your friend. Move a lamp low across the surface to highlight tracks, waves, and pinholes.

Actionable tips for better results:

- Tip 1: Tape to protect edges. A strip of painter’s tape along a crisp edge prevents accidental rounding during block sanding. Remove the tape for a final, light pass to just break the arris.

- Tip 2: Count strokes and balance pressure. When hand sanding mirrored parts, match the number of strokes and pressure on each side to keep symmetry.

- Tip 3: Use an interface pad. Add a 3–5 mm foam pad under your paper (or under your block) when sanding contours; it equalizes pressure without losing control.

- Tip 4: Clean and change paper often. Clogged paper scratches. Knock dust out frequently; replace sheets as soon as cut rate drops.

- Tip 5: Let grit do the work. If you’re pushing hard, you’re likely using the wrong grit or a dull sheet. Drop one grit coarser for a few strokes, then resume your plan.

Pressure is the most common mistake. Heavy pressure heats the surface, can gum finishes, and increases the risk of digging. Aim for steady, moderate contact. On blocks, hold with two hands—one guiding, one moderating force near the leading edge. When hand sanding, spread your fingers, keep the wrist neutral, and think “polish,” not “press.”

Materials and edges: wood, metal, and composites

Different materials respond uniquely to hand sanding and blocks. Adjust method and grit to what’s under the paper.

Wood:

- Flat panels and edges: Block first to maintain flatness. On end grain, a block reduces tearout and keeps edges true. Progress through 120–180–220 before finishing. For veneer, be cautious—use 180 and light pressure.

- Curves and profiles: Hand sanding with a soft backer shines. Shape gently at 120–150, refine to 220–320. For carved details, use folded paper supported by dowels, erasers, or shaped foam.

- Edges: Protect crisp edges with tape while block sanding adjacent faces. Remove tape and break the edge lightly by hand with 220–320 to prevent finish chipping.

Metal and body filler:

- Leveling filler: Use a long, rigid block with 80–120 to fair quickly. Crosshatch and guide coat to track highs and lows; step to 180–220 for primer.

- Curved panels and transitions: Hand sanding with a foam interface helps avoid flat spots on a crown. Blend featheredges by hand at 220–320 to avoid telegraphing.

- Heat and loading: Metal heats quickly. Lighten pressure, keep paper fresh, and consider wet sanding at finer grits if your system allows.

Composites (fiberglass, carbon, plastics):

- Flat areas: Semi-rigid or foam-faced blocks prevent “print-through” while maintaining fairness. Start at 120–180 and watch for resin-rich or fiber-rich zones.

- Curves and fillets: Hand sanding with flexible backing follows contours without cutting through edges. Use 180–320 and check often.

- Safety: Always wear a respirator and eye protection; composite dust is hazardous. Vacuum extraction helps.

Finishes and coatings:

- Between coats of varnish, lacquer, or primer, hand sanding with 320–400 (wood) or 400–600 (auto) levels nibs without burning through. Use light pressure and clean often.

- For matte finishes, uniform scratch patterns matter. Finish with the same grit across the whole area and keep strokes consistent with the final sheen direction if specified.

Edges are where quality shows. Over-rounded edges look tired; sharp, unbroken arrises chip and fail. The sweet spot: protect edges during aggressive work with tape and a block, then remove the tape and kiss the edge by hand—two or three light passes—to create a consistent, tiny bevel.

Day 4 - — Video Guide

In a concise metal-prep session, the creator tackles the spots machines can’t reach—after flattening the big, open areas, they break out sandpaper and get into door edges, seams, and tight curves by hand. It’s a classic workflow: use power or block sanding to set the overall plane, then switch to hand sanding for the fine work that determines how clean a finish will look.

Video source: Day 4 - Metal Prep on the Dart. Hand Sanding.

320 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (100-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Fine finishing grit for sanding between coats of paint, primer, or lacquer. Provides smooth, even results for woodworking, automotive, and precision finishing. Works efficiently for wet or dry applications. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: How do I avoid waves when hand sanding large flat areas?

A: Use a block on any surface that should be flat. If you must hand sand, back the paper with a firm foam pad, use light crosshatch strokes, apply even pressure with spread fingers, and check with a pencil guide coat and raking light. Switch to a long block as soon as you see unevenness.

Q: When should I choose a soft foam block instead of bare hands?

A: A soft foam block is ideal when you want hand-like conformity but need to distribute pressure evenly—think gentle crowns on panels, mild curves on wood, and primer leveling where you want to avoid finger tracking. It bridges the gap between full rigidity and bare-hand flexibility.

Q: What grit range should I use before finishing wood and before priming metal?

A: For wood before clear finishes, 150–220 is typical; dense woods can benefit from a final 320 on flat areas. For metal and body filler, fair with 80–120 on a block, refine to 180–220, then follow your primer’s recommendations (often 220–320). Always check your product’s data sheet.

Q: Is wet sanding better than dry sanding?

A: Wet sanding controls dust and can yield a finer scratch at higher grits, useful between coats of automotive finishes or for final smoothing on some paints. However, it’s not suitable for bare wood or water-sensitive materials. Dry sanding with good dust extraction is safer for wood and many fillers.

Q: How do I sand inside curves without creating ripples?

A: Wrap abrasive around a shaped backer that matches or slightly undercuts the curve—use a dowel, pencil, eraser, or carved foam. Use light, consistent strokes following the curve, step through grits (120–220–320), and check by touch and raking light. Avoid pressing with fingertip tips alone; that’s what causes ripples.