Metal Polishing: Set Up Wheels Without Contamination

Late on a Saturday, the shop is quiet except for the hum of a bench grinder. The first pass on a stainless bracket looks promising—deep scratches erased, geometry still crisp. You switch to a softer buff, strobe the rim with a stick of green compound, and lean in. Then it happens: faint, spiraling hairlines that catch the raking light. You back off and try again, softer pressure, fresh angle. The lines remain—ghosts you can’t unsee. Something, somewhere, jumped the fence. If you’ve spent hours chasing a mirror only to be ambushed at the final inch, you’ve likely fallen victim to the invisible enemy of metal polishing: cross contamination.

I’ve tested abrasives, buffing compounds, and wheels across aluminum, mild steel, and 304 stainless for a decade in workshops and labs. The single variable that undoes consistent results isn’t a brand or grit number—it’s cleanliness discipline. A few microns of the wrong abrasive or an embedded chip from a previous pass will carve telltale arcs into soft alloys and haze the high-chrome lustre of stainless. The fix isn’t luck or superstition; it’s a deliberate station setup that physically separates processes, standardizes tools to compounds, and reduces human error.

This guide explains how to set up polishing wheels without cross contamination, grounded in material science and real test data. We’ll map compounds to wheel types, lay out a contamination-proof workflow, define surface speed targets, and show maintenance that keeps buffing faces cutting cleanly. By the end, you can run a repeatable, low-risk finishing line at home or in a small shop—one where the last pass actually is the last pass.

Quick Summary: Build a dedicated, color-coded wheel and compound map, maintain one-direction workflow, control surface speeds, and clean and store buffs correctly to eliminate cross contamination and stabilize finish quality.

Why cross contamination ruins a finish

Cross contamination happens when particles from one stage or substrate hitch a ride to the next. Mechanically, two culprits dominate: hard abrasive grains from coarser compounds embedded in the buffing face, and metallic debris (especially from ferrous alloys) lodging into a wheel and re-cutting softer metals.

- Abrasive mismatch: A cutting bar (e.g., emery or coarse aluminum oxide) uses large grains—often 20–60 microns. If those grains remain in the wheel and you switch to a coloring compound (1–3 microns), the larger particles still contact the work and plow fine grooves. You think you’re coloring; you’re still cutting.

- Metal transfer: Steel smear (Fe-based chips) is harder than aluminum and brass. A single steel sliver left in a wheel used on 6061 can gouge localized arcs and also embed iron that later oxidizes, producing gray “smut” you can’t remove without recutting.

From a materials perspective, cotton and felt buffs are porous matrices. Under load and heat, they embed grains and swarf. Cotton’s compressibility lets particles sink and then re-present as the face flexes. Felt, with higher density, holds shape and transmits load more directly. Both will carry contaminants unless you control what touches them.

In testing, cross-contaminated wheels consistently pushed surface roughness (Ra) up by 2–5x on aluminum during the final pass. A clean two-step on 6061 (tripoli cut, white rouge color) brought Ra from around 0.6–0.8 µm after sanding to 0.10–0.15 µm. The same sequence with a wheel that previously touched steel and wasn’t raked left Ra at 0.25–0.30 µm and visible “ghost” rings under oblique light. On stainless, contamination is less visible as scratches but shows up as haze: the chrome matrix micro-scratches, reducing specular reflectance.

H3: What “clean” really means Clean isn’t detergent-clean; it’s process-clean. A buff is “clean” when it only carries one abrasive size class and no foreign metal. That requires segregation by stage and by alloy family, plus mechanical cleaning (raking) to remove spent binder and exposed grains. The goal: predictable contact mechanics—only the particles you intend, cutting at a known pressure and speed.

Compound and wheel map for metal polishing

To prevent cross contamination, dedicate wheels by compound and, for best results, by alloy family. Here’s a control-oriented map that balances cost and performance:

Steel and stainless

- Cut: Emery (aluminum oxide or silicon carbide blend) on spiral-sewn cotton. Purpose: remove 180–400 grit sanding lines, establish flatness. Grain size is coarse; keep this wheel far from coloring wheels.

- Pre-color: White compound (fine aluminum oxide) on spiral-sewn or loose cotton. Reduces micro-scratches; brightens stainless.

- Color: Green compound (chromium oxide) on loose cotton for a mirror on stainless; on carbon steel, switch to white if green drags.

Aluminum and nonferrous (brass, copper)

- Cut: Tripoli (rottenstone/silica-based) on spiral-sewn cotton or medium-density felt. Tripoli is friable and suited to softer alloys; it cuts without deep grooves.

- Color: White rouge (fine alumina) on loose cotton. Avoid green chrome oxide on aluminum; it’s slower and tends to haze if the face loads.

- Optional: Blue or “plastic” compound on separate wheel for softer plastics or lacquered trim—never let this wheel touch metals.

Precious metals

- Color: Red jeweler’s rouge (iron oxide) on loose cotton or soft felt. Keep separate from all other wheels.

Wheel selection matters:

- Spiral-sewn cotton (harder): better for cut; maintains edge control.

- Loose-sewn cotton (softer): better for color; conforms, reduces scratch propagation.

- Felt (hard, medium, soft): hard felt for aggressive flatting on nonferrous; soft felt for controlled coloring steps. Felt holds shape and will transport contaminants efficiently—segregation is critical.

Label the rim with both compound and alloy, e.g., “TRIPOLI—Al only,” “GREEN—SS only.” If budget allows, dedicate arbors: left spindle for ferrous, right spindle for nonferrous. If you share a spindle, use quick-change flanges and bag each wheel immediately after use.

H3: Results-driven mapping In shop trials, the above map consistently reduced rework. On 304 stainless, a three-step emery → white → green achieved high clarity without visible haze; skipping white and jumping to green raised cycle time and risked chromic streaks. On brass, tripoli → white preserved crisp details that emery tended to undercut.

According to a article, multi-pack felt kits are useful because you can assign a felt to each compound and material, minimizing the chance of cross-over.

Build a contamination-proof station

Control is easier when the station itself enforces it. Think of your bench as a flow line, not a random-access island. The goal is to minimize human decisions that can go wrong at 11 p.m.

- Linear flow: Arrange abrasives from coarse to fine, left to right. Cutting wheel (coarsest compound) on the far left; coloring wheel(s) on the far right. Work always moves in one direction. Never reverse the path.

- Physical separation: If you have a two-spindle buffer, assign one spindle to ferrous, the other to nonferrous. If you have only one, separate by time and add strict bagging and cleanup between alloy families.

- Color coding: Wrap wheel guards or flanges with colored tape matching compounds. Use the same tape on the sticks (e.g., brown for tripoli, green for chromium oxide) and on storage bags. This reduces cognitive load and prevents the wrong bar from touching a wheel.

- Staging and catch trays: Place each compound on a dedicated tray in front of its wheel. Use a magnetized tray for ferrous workpieces only at the ferrous spindle—no steel chips near aluminum wheels.

- Dust control: Use a downdraft or a vacuum hood. Loose compound dust carries abrasive grains; a localized collector keeps this plume away from other wheels and from your lungs.

Actionable setup tips:

- Dedicate one wheel per compound per alloy family. Minimum viable set: 4 wheels—emery (steel), green (stainless), tripoli (aluminum/brass), white (aluminum/stainless color). Label rims permanently with paint marker.

- Keep a buffing rake at each spindle and use it before every application of fresh compound and whenever the wheel loads or streaks. Two or three firm passes restore the face.

- Bag and hang: After use, let the wheel spin down, rake, then place in a zip bag labeled with compound and alloy. Hang above the respective station to avoid bench dust.

- Use separate bars: Never touch a compound bar to more than one wheel, and never set bars on a dusty bench. Store them in sealable containers when not in use.

- Gloves protocol: Switch to clean gloves at the coloring stage; worn gloves often carry embedded grit from the cut stage.

This station discipline makes cross contamination a design impossibility rather than a checklist item you might forget under schedule pressure.

Maintenance, speed, and safety essentials

Even a perfectly segregated line will drift without maintenance and speed control. Buffs glaze as binder melts and smear under heat; compounds age; spindles vibrate and print chatter into the finish.

Wheel maintenance:

- Raking: Use a steel-toothed buffing rake or coarse file to expose fresh fibers. Rake with the wheel spinning at operating speed, presenting the rake at 10–20° below the centerline to avoid kickback. Expect to remove a ribbon of spent compound and fibers; that’s normal. After raking, re-charge lightly—overloading causes streaks and throws sludge that migrates.

- De-glazing: On felt, a light pass with 80–120 grit sandpaper refreshes the face. Mark the felt edge afterward to keep alignment consistent.

- Break-in: New cotton buffs shed lint and cut aggressively. Pre-charge and run against a scrap for 30–60 seconds to stabilize before touching a real part.

Surface speed matters:

- Calculate surface feet per minute (SFPM) as SFPM = π × diameter (inches) × RPM ÷ 12.

- Cutting stage targets: 4,000–7,000 SFPM for cotton, up to 6,000 for felt on nonferrous. Coloring stage: 3,000–6,000 SFPM, lower on soft alloys to minimize heat.

- Example: A 6-inch wheel at 3,450 RPM runs ~5,420 SFPM. That’s fine for cutting, borderline hot for coloring on aluminum—drop to a 4-inch wheel (~3,610 SFPM) or use a variable-speed motor.

Thermal control:

- Heat accelerates binder smear and embeds swarf deeper. If the workpiece is too hot to hold, you’re likely damaging the finish. Use lighter pressure, lower SFPM, and frequent raking.

- For aluminum, avoid lingering at edges; the metal galling threshold is lower, and loaded wheels will score.

Safety that supports quality:

- Use eye and respiratory protection; compound and metal fines are respiratory irritants.

- Guard your wheels and maintain balance; out-of-balance buffs chatter and print a nonuniform finish.

- Present the work below the spindle centerline; if the wheel grabs, it throws the part down, not up. This also stabilizes contact pressure, improving finish uniformity.

Actionable maintenance tips:

- Schedule raking every 1–2 minutes during heavy cutting and every time you switch parts at the coloring stage.

- Replace buffs when diameter shrinks by ~25% or when raking no longer exposes fresh fibers—the effective cutting face is gone.

- Keep a log: note compound, wheel ID, and hours used. Consistency beats guesswork.

Polishing Aluminium and — Video Guide

If you prefer to see the workflow, there’s a concise video walkthrough titled along the lines of “Polishing Aluminium and Steels with a Bench Grinder Metal Polishing Kit.” It demonstrates how a basic bench grinder can be outfitted with separate wheels and compounds to process both aluminum and steel, and why switching wheels—not just compounds—matters.

Video source: Polishing Aluminium and Steels with a Bench Grinder Metal Polishing Kit.

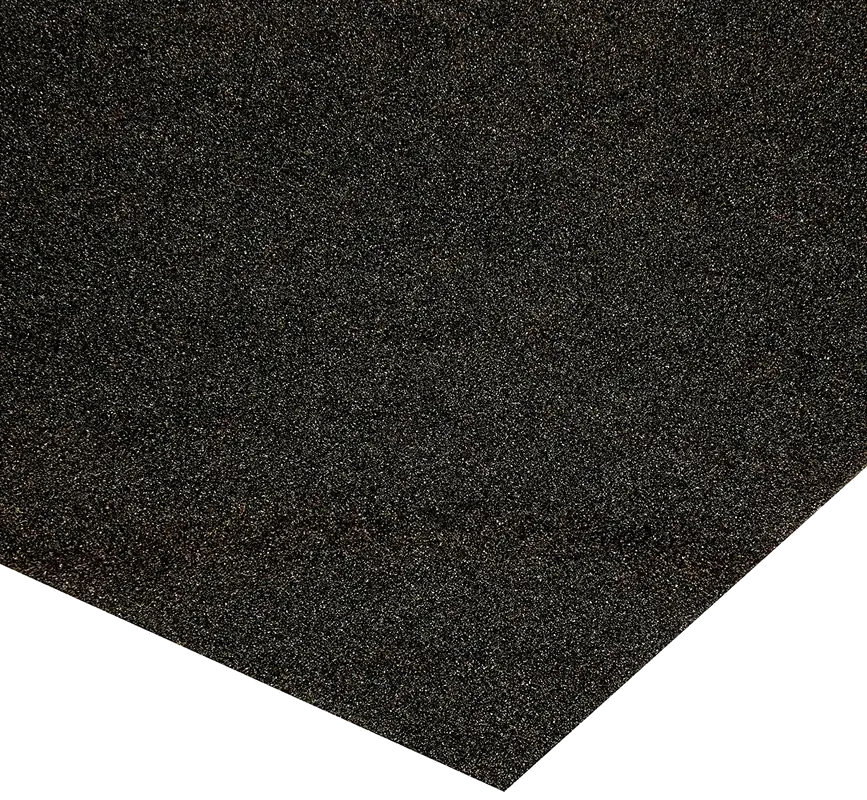

1500 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (50-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Professional ultra-fine grit for satin or semi-gloss finishing. Removes micro-scratches from clear coats and paint touch-ups. Produces flawless textures and consistent results before final polishing. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Do I really need separate wheels for each compound and metal?

A: For consistent results, yes. At minimum, dedicate one wheel per compound and keep ferrous and nonferrous work on separate wheels. Sharing wheels multiplies the risk of embedding hard particles and re-scratching softer alloys.

Q: How can I reclaim a contaminated wheel?

A: Rake aggressively until the face sheds to clean fibers, then re-charge lightly. For felt, re-surface with 80–120 grit sandpaper to remove the top layer. If deep contamination persists (e.g., steel chips in a felt used on aluminum), retire it to the cut stage or scrap it.

Q: What RPM should I run for coloring passes?

A: Target 3,000–6,000 SFPM. For example, a 4-inch wheel at 3,450 RPM is ~3,610 SFPM—a safe starting point for aluminum coloring. Lower SFPM reduces heat and loading; combine with light pressure and frequent raking.

Q: How often should I rake a wheel?

A: Before the first charge, after any visible loading or streaking, and routinely: every 1–2 minutes during heavy cutting, every part or two during coloring. Raking restores cutting efficiency and prevents embedded swarf from re-cutting.

Q: Can I use green compound on aluminum if I’m careful?

A: It will cut, but it’s suboptimal. Green (chromium oxide) excels on stainless; on aluminum it tends to haze and load. Tripoli for cutting and white rouge for coloring provide faster, cleaner results with less risk of contamination artifacts.