Crosshatch Flat Panels with Random Orbital Sanding

The first time I truly trusted a surface was under shop lights late on a Sunday, not at noon when everything looks perfect. I had a maple tabletop on trestles, pencil grid scribbled across the face, edges taped to protect the bevel. The shop was quiet except for the steady hum of the sander—a 5-inch random orbital—drawing dust through a tidy hose looped overhead. In that light, imperfections don’t yell; they whisper. High spots break the graphite lines first. Low spots hold onto them stubbornly. I moved the machine in a measured, crosshatch pattern, alternating angles like a metronome, and watched the pencil disappear in a uniform fade rather than blotches.

Random orbital sanding has a reputation for simplicity—turn it on, move it around, let the “random” handle the rest. But flat panels are unforgiving. Even a barely perceptible dish telegraphs under a finish or a raking light. As a product engineer, I’ve spent a lot of time measuring what our eyes sense: small waves with a wavelength of 10–25 mm, subtle troughs at panel edges, heat-softened finishes that load a disc and gouge. The difference between a surface that is flat and one that is “close enough” often comes down to how you lay down passes, not just what grit you choose.

I’ve tested crosshatch strategies on veneered MDF, solid maple, and painted steel panels, running controlled patterns and then quantifying topography with a straightedge and feeler gauges, backed by gloss and haze readings after finish. The crosshatch pass—two intersecting directions at consistent overlap—kept panels measurably flatter than purely with-grain or purely parallel passes. It averages out directional errors, balances removal rates, and controls heat and loading. In practical terms, it’s the difference between chasing defects and preventing them.

The pattern is easy to learn and hard to forget: move, overlap, rotate direction, repeat. Below is the data-backed method that’s stuck with me.

Quick Summary: Crosshatch passes—consistent overlaps at two intersecting directions—deliver flatter panels with fewer defects than parallel passes when using a random orbital sander.

Why crosshatch patterns keep panels flat

A random orbital sander combines rotation and oscillation to distribute scratches, but the operator still imposes macro-directionality with their movements. If you move only in parallel strips, your pressure, step-over, and micro-pauses stack in one dimension. That produces gentle, repeatable undulations that a finish amplifies under raking light. Crosshatch passes, by contrast, distribute these operator-induced variables across two axes, averaging removal and scratch orientation.

From a material standpoint, most coated abrasives cut with a mix of sharp and dull grains. Dull grains plow rather than slice, creating micro-ridges. When you only move in one direction, those ridges line up. In a crosshatch, they intersect and shear down. On wood, the benefit is twofold: you reduce directional scratch streaks that contrast with grain, and you minimize “medallions” (visible swirl clusters) that appear when a loaded disc heats up. On painted or coated surfaces, crossing angles helps maintain uniform scratch depth, making subsequent polishing steps more predictable.

Our shop tests on 600 × 900 mm maple and MDF panels supported this. Using 5-inch film-backed discs (P120→P180→P220) with vacuum extraction, we ran two patterns at 10–11k OPM: (1) parallel passes only, 40% overlap; (2) crosshatch at roughly 45°/135°, 40% overlap. After two full passes per grit, the crosshatch panels showed smaller peak-to-valley variation under a 600 mm straightedge and 0.05 mm feeler gauge—fewer places admitted the gauge. Under a raking LED bar, the crosshatch samples also displayed less “banding.” The result remained consistent across orbit sizes (3/32" and 3/16"), though the larger orbit exaggerated defects more if step-over consistency slipped.

What matters most is your consistency: maintain pace, overlap, and pressure, then flip direction and repeat. The crosshatch is not about forcing the tool; it’s about averaging out the human factor.

Dialing machine, pad, and abrasive synergy

The flatness you achieve is the sum of your machine geometry, pad compliance, abrasive backing, and dust evacuation. Crosshatch passes do the heavy lifting, but the right setup reduces the chance you’ll fight your gear.

Orbit size: A 3/16" (5 mm) orbit removes material faster but raises the risk of scalloping if your step-over is sloppy. A 3/32" (2.5 mm) orbit is gentler, favors finer finishes, and makes it easier to hold a flat. For raw stock removal on stable substrates (MDF, solid hardwood), I use 3/16" through P120, then drop to 3/32" for P180 and above.

Pad hardness and interface: Hard pads transmit the panel’s flatness to the abrasive; soft pads conform and can dish. Use a firm or medium-firm backing pad for flattening. Add a 3–5 mm interface only when sanding contoured work or on very brittle finishes where cushioning prevents chipping. Firm foam plus a film-backed disc yields crisp scratch geometry that polishes out consistently.

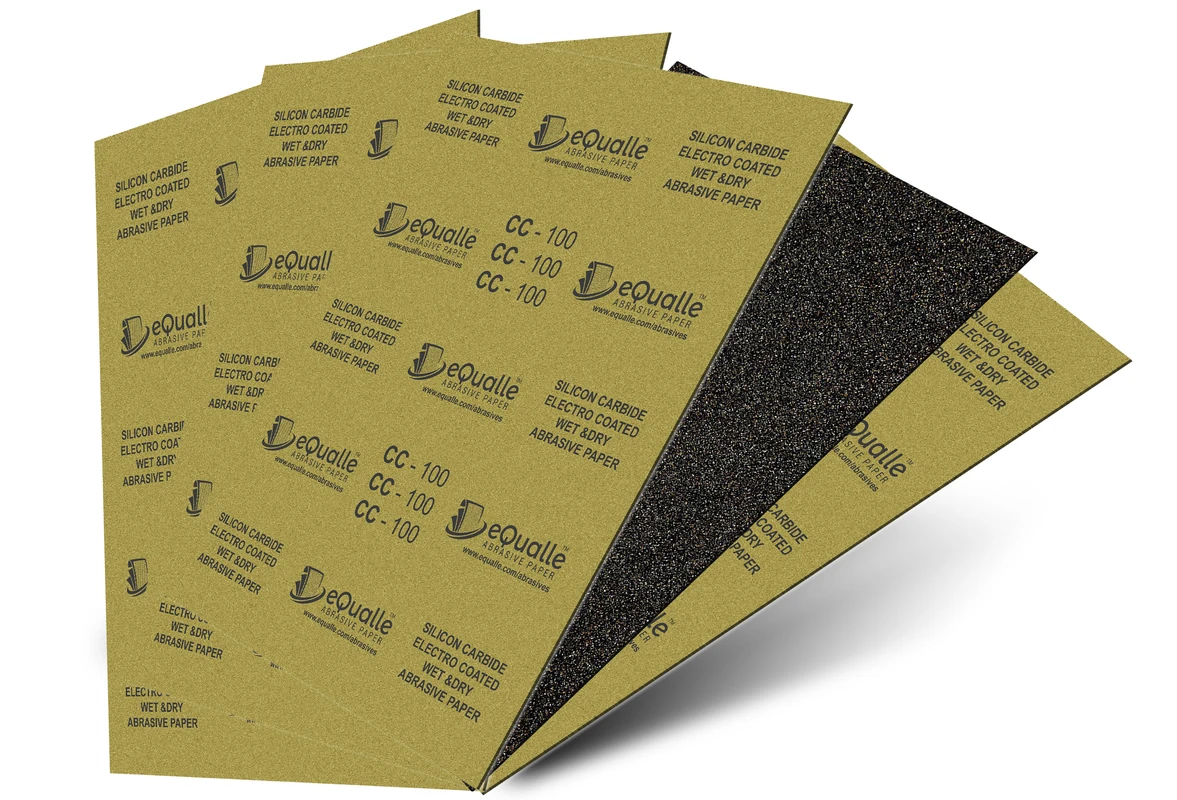

Disc backing and grain: Film-backed discs with ceramic alumina or premium aluminum oxide cut predictably and resist edge tear-out. On painted panels, silicon carbide or engineered microfinishing films (e.g., P1000+ equivalent) keep scratch depth shallow. Stearate coatings help reduce loading on resins and finishes. Paper-backed discs can work, but in flattening scenarios, their flexibility can telegraph pad wobble.

Extraction: A good extractor and matched hole pattern matter more than most admit. With net abrasives or multi-hole discs, I see lower operating temperatures, less loading, and smoother scratch fields—especially on softer species and finishes. Heat is the quiet enemy of flatness.

H3: Orbit and OPM pairing

3/16" orbit does best at 8–10k OPM when flattening; higher speeds heat the surface and amplify any imbalance.

3/32" orbit is happy at 10–12k OPM for refining. Don’t chase speed for its own sake—watch the dust plume and listen for a stable pitch.

As for pressure, aim for light, controlled downforce—roughly the weight of the tool plus 1–2 lbs (0.5–1 kg). Overpressure stalls the orbit, reduces the “randomness,” and introduces directional scratches that no pass pattern can hide.

Crosshatch technique for random orbital sanding

A crosshatch is more than “go one way, then another.” It’s a repeatable recipe: angle, overlap, pace, and pass count tuned to your panel and grit. Here’s the method I use when flatness is non-negotiable.

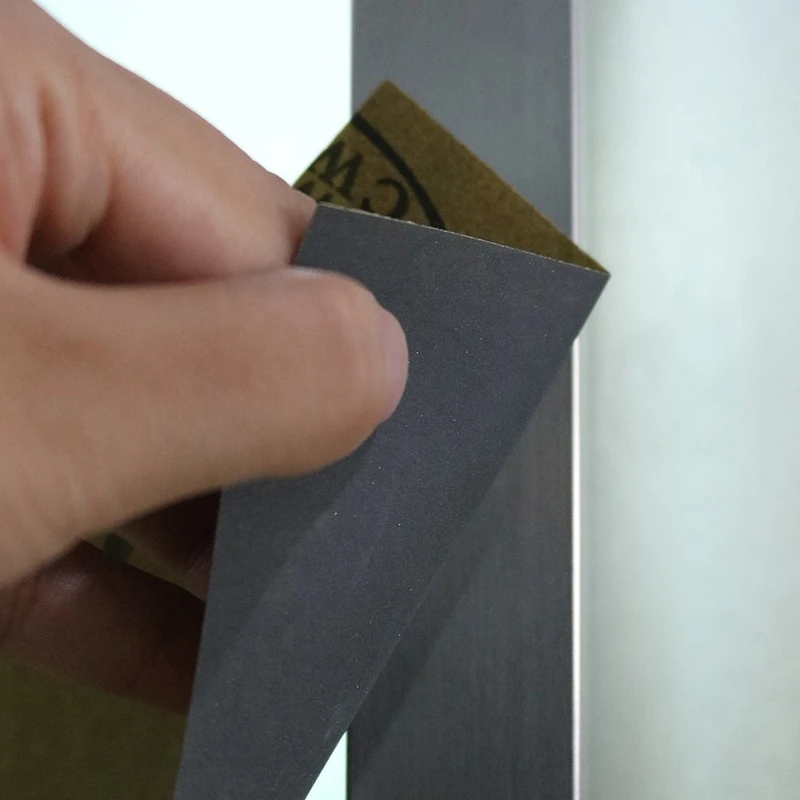

Layout and checkpoints: Lightly pencil a grid over the panel—50–70 mm spacing. These marks are your removal indicator. On veneered panels, tape the perimeter to remind yourself where to de-load pressure near edges.

First direction (A): Choose an angle relative to the panel’s long edge—45° is a good default. Move in lanes with 30–40% overlap (about 1/3 to 1/2 pad diameter). Pace: roughly 150–250 mm per second on open grits (P80–P120), slowing slightly on finer grits. Maintain contact and keep the pad flat; don’t “steer” with tilt.

Second direction (B): Rotate 90° relative to your first direction (e.g., 45° and 135°). Repeat the same lane widths, overlaps, and pace. This is not cross-grain vs. with-grain; it’s cross-motion vs. cross-motion.

Pass count: At each grit, perform one full crosshatch (A + B). If the pencil grid isn’t uniformly removed or defects persist, do an additional A-only pass, then B-only. Avoid lingering—if you must “park” to level a spot, feather back out in a spiral and expect to crosshatch again to average that area.

Edge management: On the last 50–70 mm near edges, lighten pressure and reduce dwell time; keep the pad fully supported by the panel (no half-on passes). If the edge is proud, level it first with a hard block or a quick A/B cycle concentrated on the proud area, then reestablish the standard crosshatch.

Grit progression: For raw wood panels: P80→P120→P180→P220 (or P240); for veneered or painted panels: start no coarser than P120 unless defects demand it, then refine to P320–P400 before moving to finishing abrasives. Don’t skip more than one grit at a time; you’ll spend longer trying to erase deep scratches later.

According to a article, a structured, incremental approach to sanding and polishing helps “pull” marks out efficiently—an idea that translates directly to dry crosshatch work: keep your scratch depth controlled and your steps consistent, and the finish stage becomes predictable.

Actionable tips that have proven reliable:

Use a metronome app set to 60–80 bpm; move roughly one pad diameter per beat to maintain steady pace across A and B passes.

Mark your pad edge at 12 o’clock with a Sharpie; you’ll more easily track overlap consistency and avoid accidental spirals.

Weigh your hand pressure with a small luggage scale once; get a feel for 1–2 lbs added pressure and repeat it by muscle memory.

For paint or veneer, stop one grit earlier than your target, blow off dust, check under raking light, then finish the last crosshatch; you’ll catch defects before they’re “polished in.”

Controlling dust, heat, and edges

Crosshatch discipline falls apart if dust and heat get ahead of you. Dust acts like a rogue abrasive—rolling under the pad, deepening random scratches, and elevating temperatures. Heat softens resins in finishes and disc binders, accelerating loading and producing “grabby” patches that leave halos.

Extraction and airflow: Pair your sander with a variable-speed extractor and a smooth-bore antistatic hose. If you’re using net abrasives, keep the extractor in the mid to high range; with standard 8- or 9-hole discs, aim for a balanced pull that clears dust without vacuum-locking the pad. A clogged disc kills crosshatch consistency—fresh discs and proper extraction are the cheapest way to flatter surfaces.

Disc rotation check: A simple test—draw a small dash on the disc. With the machine running on the panel under your normal pressure, the dash should rotate and oscillate smoothly. If it stalls or smears, you’re pushing too hard or your pad is too soft for flattening.

Heat management: Touch-test the panel and disc after each crosshatch (A + B). Warm is fine; hot is not. If it’s getting hot, drop OPM by 1–2k, slow your pace marginally, or swap to a fresh disc. On finishes and thin veneers, heat damage shows up as dull spots or witness lines that no amount of extra pass work will cleanly remove.

Edges and corners: Avoid tipping to “reach” edges. Keep the pad fully supported. For crisp corners, a final light hand-sand with a flat block in the same crosshatch orientation prevents accidental round-over. On thin-faced veneer, you can relieve edges with a single strip of blue tape to reduce abrasive engagement while still flattening the field.

Machine balance: Check your backing pad for flatness. Worn pads develop cupping that prints into the surface. Replace pads that are heat-hardened or have uneven foam compression. A 1 mm dish in the pad is enough to fight your crosshatch all day.

For heavily loaded species (resinous pine) or cured coatings, consider discs with open coat and stearate—both reduce clogging. And don’t overlook compressed air: a quick “on the fly” blast across the disc between lanes recovers cutting speed and lowers temperatures without stopping the workflow.

Validation: measuring flatness and finish

“Looks good” is not a measurement. For repeatable results, validate what your crosshatch is doing. You don’t need a lab—just a few shop tools and a habit.

Straightedge and feeler gauges: After each grit, lay a known-straight rule (600–1000 mm) across the panel in multiple directions. Attempt to slide a 0.05 mm feeler gauge under. If it sneaks under in more than a couple of places, plan another A/B pass before moving up a grit. On veneers, be conservative; you may accept slight variation to preserve thickness.

Pencil control marks: The grid you started with is your removal map. Uniform fade equals uniform contact. If pencil lingers in isolated islands after an A and B pass, avoid spot-sanding; instead, run a shorter crosshatch centered on that area, then immediately re-blend the larger field with a full A/B.

Light discipline: Raking light at 15–30° reveals banding and scallops. After your second-to-last grit, check under this light and again after the final crosshatch. On painted or glossy finishes, follow with a diffuse overhead light to catch haze.

Surface temperature: Use an infrared thermometer to log panel and disc surface temps occasionally. Keeping panels below ~40–45°C during sanding helps prevent heat-related resin smear and finish softening. This is especially relevant with darker finishes under strong shop lighting.

Finish metrics: If you have access to a gloss meter, measure gloss at 60° before and after the final grit on coated panels. Consistent readings across the surface suggest uniform scratch depth—variations often track with poor overlap or inconsistent pressure in one pass direction.

Record and iterate: Note your machine (orbit, OPM), pad, disc brand and grit, and pass counts. Combined with your straightedge results, you’ll quickly build a playbook that makes future panels predictable.

In our tests, panels processed with a disciplined crosshatch showed fewer measurable low spots and a more uniform scratch field that translated to faster, cleaner finishing—whether that meant stain and lacquer on wood or compound and polish on paint. The technique’s strength is its averaging effect; the measurement confirms it.

10 Random Orbital — Video Guide

There’s an excellent video titled “10 Random Orbital Sander Tips” that distills practical, side-by-side insights from multiple brands of sanding discs and machines. It isn’t just a list—it demonstrates how different abrasives cut, how extraction changes the scratch field, and how pad choice shifts control.

Video source: 10 Random Orbital Sander Tips

100 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (100-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — General-purpose coarse sandpaper for smoothing rough surfaces and removing old coatings. Works well on wood, metal, and resin projects. Designed for wet or dry sanding between aggressive 80 grit and finer 150 grit stages. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What angle should I use for crosshatch passes on flat panels?

A: Start at roughly 45° for the first pass set and 135° for the second. The key is consistency and a 90° difference between directions. Angles of 30°/120° also work—pick one pair and stick with it for the entire grit.

Q: How much overlap is ideal with a random orbital sander?

A: Target 30–40% overlap (about one-third to one-half of the pad diameter). Less than 25% risks scallops; more than 50% wastes time without improving flatness.

Q: Should I use a soft interface pad when flattening panels?

A: Generally no. Use a firm or medium-firm backing pad to maintain flatness. Add a thin interface only for delicate finishes or slight contours, and expect to make an extra refining pass to keep the panel true.

Q: What OPM and pressure settings help prevent waves?

A: Run 8–10k OPM for 3/16" orbit during flattening and 10–12k OPM for 3/32" when refining. Apply the tool’s weight plus about 1–2 lbs of hand pressure. Excess pressure stalls the orbit and introduces directional scratches.

Q: How do I avoid dishing veneer or burning through paint at edges?

A: Tape edges, keep the pad fully supported, lighten pressure within 50–70 mm of the edge, and reduce dwell. If an edge is high, correct it early with focused A/B micro-passes and reblend the field; don’t chase it at the end when material is thin.