Reduce Swirl Marks with Polishing Sandpaper

The garage is quiet except for the hum of an overhead light and the soft grit-on-clearcoat whisper from a half-used sheet of polishing sandpaper. You’ve taped your edges, dialed in the work light, and set a microfibre towel neatly across the fender. Under diffused lighting the finish looks clean, but tilt the panel toward a harsh LED and the surface blooms with holograms—pinwheel arcs that betray rushed prep, mismatched abrasives, or a pad that was a little too warm for a little too long. It’s frustrating because the underlying paint is healthy and thick; you’ve done the right passes, but the micro-marring remains.

If this scene feels familiar, you’re not alone. Swirl marks are rarely the fault of a single misstep. They accumulate from a stack-up of small variables: a grit jump that was too aggressive; film-backed paper used dry, clogging and scratching; a compound that flashed before you finished the section; or a pad that carried dried residue from the last panel. The good news is that swirls are predictable, and anything predictable is preventable. With precise abrasive selection, measured machine movements, and clean, repeatable workflows, you can reduce haze and holograms dramatically, even on sensitive dark finishes.

The trick is to think of the finish as a micro-topography you sculpt in stages. Each step should refine the previous step’s scratch pattern, not reinvent it. That means understanding how abrasive minerals fracture, how backing materials conform, and how heat and residue affect the surface you’re leveling. You don’t need exotic tools; you need discipline: consistent pressure, true passes, clean pads, correct lubricants, and the right polishing sandpaper in the right grit at the right time. Once those elements align, the paint stops fighting you, and the gloss comes up fast and clean.

Quick Summary: Eliminate swirl marks by controlling abrasive size and type, refining scratch patterns stepwise, managing heat and residue, and inspecting under proper lighting.

Why Swirl Marks Appear

Swirl marks are essentially directional micro-scratches that high-angle light reveals. The mechanics are simple: an abrasive particle cuts a groove; if the next process leaves a scratch that’s not shallower and more uniform than the previous, you’ll see haze or distinct arcs. On a rotary, pad rotation can align micro-marring into visible holograms. On a dual-action (DA), poor technique can create DA haze—uniform but shallow micromarring that dulls clarity. In both cases, the root causes fall into a few categories.

First, abrasive mismatch. Jumping from P1000 straight to a finishing polish expects the pad and liquid to remove scratches far larger than they’re designed to handle. Every stage must reduce the previous scratch depth by roughly 50–70% and unify directionality. Second, contamination. A clean panel can still pick up rogue grit from a dirty pad face, crumbling backing plate edge, or airborne dust. One embedded grain in a foam pad acts like a random cutter that draws isolated but deep trails across the finish. Third, heat and softening. Clear coats soften as surface temperature rises; softened resin smears under pressure, then rehardens with an uneven, sheared texture that reflects light as haze or ghosting.

Fourth, pad and backing dynamics. A foam pad’s cell structure and density determine how well it conforms and carries abrasives. A backer plate with the wrong stiffness telegraphs high spots, creating uneven pressure and scalloping, especially near edges. Fifth, residue handling. Spent abrasive and binder accumulate on the pad and in the compound film. If not cleared, the slurry thickens, clumps, and scratches. Finally, motion and pressure. Inconsistent arm speed, uneven downforce, and overlapping patterns that are too narrow or too wide can leave islands of unrefined scratches sitting next to fully refined areas. Control these inputs, and swirls diminish before you even reach the finishing step.

Grit Progressions and Polishing Sandpaper

Abrasive progression is the backbone of swirl-free finishing. Start by aligning on grit scales: FEPA “P” grades (P800, P1500, P2000) differ from CAMI (800, 1500, 2000) and micron-rated films (30 µm, 15 µm, 10 µm). Know your system and stick to it. Aluminum oxide offers durable, consistent fracture for general paint work; silicon carbide cuts fast and sharp, ideal for hard clears and wet sanding; ceramic abrasives in film discs provide long life and very uniform scratch patterns. Film-backed sanding media with a foam interface pad distribute pressure evenly and dramatically reduce rogue scratches compared to paper-backed sheets.

A reliable progression for typical clear coat repair might be: P1200 or P1500 (defect removal) → P2000 → P3000/Trizact (~5–10 µm) → compound → polish → optional jeweling step. The key is overlap: don’t skip intermediate steps unless your test spot proves it’s safe. Each grit should remove the previous scratch quickly and uniformly; if you’re spending more than a minute per 12"×12" section with a given sanding step, either the previous step was too coarse or the current abrasive is dull or clogged.

Wet sanding minimizes dust and carries swarf away from the contact patch, reducing pigtails. Use clean water with a small amount of surfactant (a drop of car shampoo per spray bottle) to improve glide and prevent loading. Keep strokes linear in a cross-hatch (0°/90°) so you can see when a scratch family is fully replaced. Switch to a fresh piece of polishing sandpaper before performance falls off; dull grains burnish instead of cut, smearing the resin.

Actionable abrasive tips:

- Always identify and mark your deepest defects; size your starting grit to those, not the average field of scratches.

- If your P2000 step takes more than 50% longer than P1500 in the same area, you likely need a P1800/P2500 bridge.

- Use a 3–5 mm foam interface under film discs for curved panels to prevent edge-cut pigtails.

- For soft clears, swap silicon carbide for aluminum oxide in the final sanding step to reduce micro-chipping.

Machine Choice, Pads, and Compounds

Your machine and pad system translate abrasive intention into surface reality. Dual-action polishers with long throws (15–21 mm) reduce the risk of holograms and are forgiving on most clears. Forced-rotation DAs add cut without full rotary risk. Rotary polishers cut fastest and finish incredibly well in skilled hands, but they localize heat and can imprint holograms if technique or pad choice is off. Choose the least aggressive tool that achieves your target in a test spot.

Pad materials dictate contact mechanics. Wool and twisted wool maximize cut by presenting many sharp fibers; they run cooler but can leave micro-tracking that requires a refining step. Microfiber pads cut hard with uniform fibers and often finish surprisingly well on medium clears. Foam pads span the spectrum: high-density closed-cell foams for cutting, open-cell medium foams for one-steps, and very soft, low-density foams for final finishing. Priming matters—fully butter the pad face for microfiber and wool; lightly prime and blot off excess for foam to avoid micro-hazing. Clean on the fly by blowing pads with compressed air or brushing out residue every section or two.

Compounds combine abrasives and lubricants. Diminishing abrasives fracture to finer sizes as you work; non-diminishing abrasives maintain size, relying on your passes for refinement. Either can finish well if used correctly. Work in modest section sizes (12"×12"), consistent arm speed (~1–2 inches per second), and 30–50% overlap. Keep panel temperatures under ~120°F/49°C—too hot, and resins smear; too cold, and lubricants underperform.

According to a article you can exacerbate swirls by sanding in circular hand motions and by bridging grits too aggressively, making the polishing stages do too much heavy lifting. The remedy is a disciplined cross-hatch with measured grit steps, followed by pad/product combinations proven in a test spot. Adjust variables one at a time: if haze persists, try a softer finishing pad with the same polish; if RIDS remain, step back a grit or switch to a cutter with more bite, then re-refine. Small, controlled changes beat wholesale product swaps every time.

Workflow: From Cut to Finish

Success comes from a repeatable sequence and tight feedback loops. Begin with decontamination: wash, chemically decon for iron and tar, then clay with abundant lubricant. Tape edges, trim, and high spots. Measure film thickness if possible and mark thin areas; swirls don’t justify burning through. Establish a test spot that represents the worst of the panel. Decide whether sanding is required—if defects are deeper than the expected compound’s cut, sand; if not, start with a least-aggressive pad/polish combination.

Sanding workflow: select your starting grit based on the deepest defect you plan to remove, not the overall haze. Use film-backed media with a soft interface, wet-sand in linear passes, and stop early to inspect. Wipe with a dedicated panel wipe (no silicone carriers), dry thoroughly, and use cross-lighting to verify the previous scratch family is fully replaced. Move up one grit. The moment you see uniform scratch orientation and depth, you’re done with that grit. Overworking a step just creates more to remove later.

Cutting and refining: for compounding, set the machine speed to the low-middle of its range, apply minimal but even pressure, and lock your arm speed. Make 4–6 slow passes with 30–50% overlap. Wipe, inspect under a handheld, high-CRI light. If clarity is good but faint haze remains, switch to a polishing pad and fine polish. Finish with a slow, low-pressure “jeweling” pass on soft foam at low speed, especially on dark colors. Keep towels clean and folded; dedicate sides and inspect for debris before each wipe.

Process control tips:

- Reset pads frequently; one saturated pad will reintroduce haze across the entire panel.

- Refresh compound dots every section; a dry film abrades unpredictably.

- If a section feels grabby, stop and re-lubricate or swap to a fresh pad; don’t fight friction.

- After each major step, do an isopropyl alcohol (IPA) or panel-wipe check to eliminate filling and reveal the true surface.

Inspection, Lighting, and Defect Control

You can’t remove what you can’t see. Inspection lighting should alternate between diffuse and specular sources. Diffuse light (soft shop lights) shows texture and leveling; specular point sources (handheld LEDs at 5000–6500 K, high CRI) reveal swirls and RIDS. Move the light along shallow angles to graze the surface; rotate around the panel to catch directional holograms. For final verification, step outside under direct sun or use a color-matched, focusable swirl-finder.

Environmental controls matter. Work dust-free; a single airborne grit can undo a perfect finish. Vacuum, mist the air lightly to settle particles, and keep a dedicated “finishing zone” with clean towels and pads. Temperature and humidity influence lubricants—higher temps shorten workable time; high humidity can slow flash and smear. Adjust machine speed or product amount accordingly. Manage edges and contours with reduced pressure and slower passes; the contact patch shrinks on convex areas, amplifying pressure and heat.

Towel discipline is often overlooked. Use edgeless, 300–500 GSM microfibers for wipe-off; pre-wash new towels to remove manufacturing lint. Fold twice to create eight clean quadrants; flip to a fresh face after each pass. Launder separately, no fabric softeners, low-heat dry. Finally, avoid reintroducing defects after polishing: install protection (sealant or coating) with the softest applicator, and use contactless wash methods afterward. If you need a final sanity check, do a controlled, low-pressure, single-pass wipe and re-inspect—if you see new lines, pause and re-evaluate towels and environment. Attention here preserves the work you invested upstream—and ensures that the careful selection of abrasives and polishing sandpaper truly pays off in optical clarity.

Polishing with a — Video Guide

If the rotary scares you, this concise demonstration breaks down finishing with a direct-drive machine into straightforward, repeatable steps. You’ll see how pad choice, machine speed, and arm movement affect holograms, and how minimal pressure with a soft finishing pad can deliver a crisp, hologram-free finish.

Video source: Polishing with a rotary made easy.

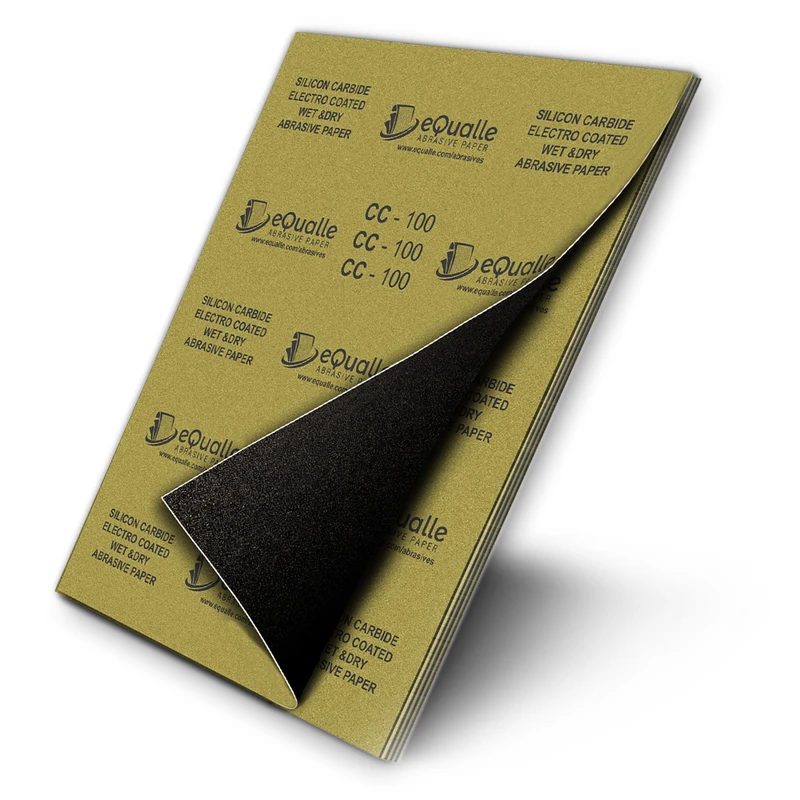

1500 Grit Sandpaper Sheets (100-pack) — 9x11 in Silicon Carbide Abrasive for Wet or Dry Use — Refining grit that bridges polishing and buffing—perfect for restoring a subtle satin or semi-gloss look on painted finishes. (Professional Grade).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Are circular hand-sanding motions really a problem?

A: Yes. Circular strokes create multi-directional scratch families that are harder to refine. Use linear, cross-hatch passes so each subsequent grit clearly replaces the previous pattern.

Q: Should I wet or dry sand before polishing?

A: Wet sanding with film-backed abrasives and a mild surfactant minimizes clogging and rogue scratches, especially at P1500 and finer. Dry sanding is faster for initial leveling but raises heat and dust; finish wet for a cleaner, more uniform scratch.

Q: What grit should I stop at before switching to compound?

A: On most clears, finish sanding at P3000 (or ~5–10 µm film) before compounding. Harder systems may need P2000 → P3000; softer systems can sometimes go P2500 → finish polish. Validate with a test spot.

Q: How do I avoid DA haze on dark colors?

A: Reduce pad aggressiveness, lower machine speed, and lengthen your finishing cycle with a soft foam pad and fine polish. Keep pads impeccably clean and perform a panel-wipe check to ensure you’re not masking haze with lubricants.

Q: How often should I clean or change pads?

A: Blow out or brush pads every section; swap pads every 2–3 sections when compounding and every 3–4 sections when finishing. Heat and residue buildup are prime drivers of micro-marring and swirls.